From Camp Upton to NSLS, Five Generations At Brookhaven Lab

November 7, 2012

When Julius Makra came to New York by boat from his native country of Hungary in the years before World War I, he had no idea that his employment at the Camp Upton Army base on Long Island would set into motion what may be Brookhaven Lab’s longest running lineage. Now, roughly 100 years later, Makra and the four generations that have followed make up a remarkable snapshot of the Lab at distinct points in its history, from military base to world-renown research institution.

Three generations of Kisses on site at the annual Photon Sciences barbeque this summer (from left): Bob, Cody and Sonya

Born in 1888, Makra came to Camp Upton allegedly to work as a cook, though no one can say for sure the exact dates or Makra’s employment history due to a record-destroying fire, says his grandson Bob Kiss, a mechanical technician and longtime employee of the Lab who now works in the Photon Sciences Directorate as a research space coordinator at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS).

Makra’s son-in-law and Bob’s father, Stephen Kiss, came to work at the Lab 15 years after it was formally established in 1947 on the Camp Upton site. Working in the eighty-inch bubble chamber that detected particles from the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron, Stephen would sometimes bring Bob to the Lab. “I used to come out here at night with him,” Bob says, “And it was a lot different. There sure was no expressway coming out here.”

After going to school for mechanical engineering with the intent on becoming a mechanical technician, Bob joined the Brookhaven staff in 1977 at the seven-foot bubble chamber that replaced the one his father worked on only a few years earlier.

In 2008, Bob’s daughter Sonya joined the Lab in the clerical pool, working at the clinic for short time before moving to the Environmental Restoration Group that was created in 1990 to begin the decommissioning of the site’s nuclear reactors. Sonya now also works in the Photon Sciences Directorate as an administrative assistant.

And almost three years ago, the fifth generation of the Makra-Kiss line joined Brookhaven Lab, as a day-care attendee. “He was four months old when he started,” Sonya says of her son Cody, who will be three years old this December.

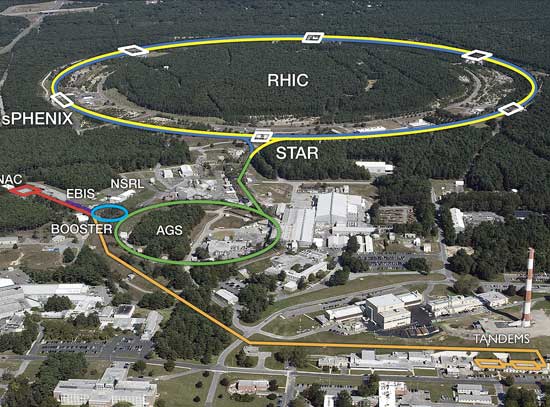

Over the years, Brookhaven has undergone a series of geographic changes in-step with the immense scientific tools that have been implemented on site. Bob remembers how, in the late 1970s, the building housing the seven-foot bubble chamber he worked on was the northernmost structure on site. It was surrounded by forest on its edges and the wide expanse of empty fields. Now, the space houses the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and its 2.4-mile underground tunnel.

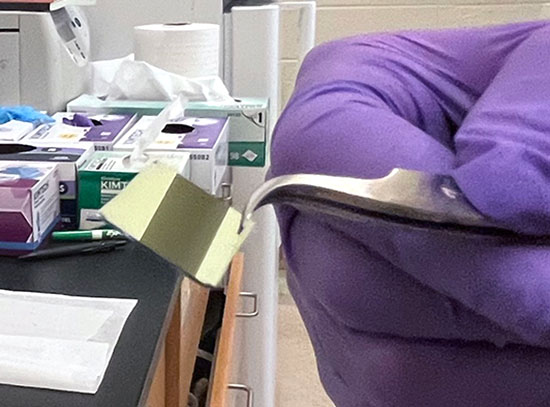

Sonya recalls when she first joined the Environmental Restoration Group. “I had the privilege of working with a bunch of people that my dad worked with in the HFBR [High Flux Beam Reactor] because they were part of the decommissioning group. First thing I hear from them is, ‘Oh my God, I remember you when you were ‘this’ big’,” Sonya says, holding her hand only three feet or so above the ground.

One of Sonya’s duties when she first joined the group was to archive all the records, and she recounts the time when she came across her father’s signature, recognizing his handwriting, on years-old documents from when he was a supervisor at the HFBR.

For Sonya’s son Cody, it’s far too early to tell whether or not his family’s history at the Lab will influence him to pursue engineering or another science-related field, and whether that will bring him to Brookhaven for a career. “Wherever his heart takes him,” Sonya says of her son’s future.

“But he’s got a very inquisitive mind,” Bob responds with a laugh.

2012-3472 | INT/EXT | Newsroom