Personality-Influencing Gene May be a Key to Long Life

January 3, 2013

The human genome is like a roadmap for the body, but our understanding of the road signs that point some people toward a long life and others to an early death is still limited. Now, research from the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of California, Irvine, finds that genes involved in regulating personality may also be keys to longevity. Study results appear online in the January 3, 2013, issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

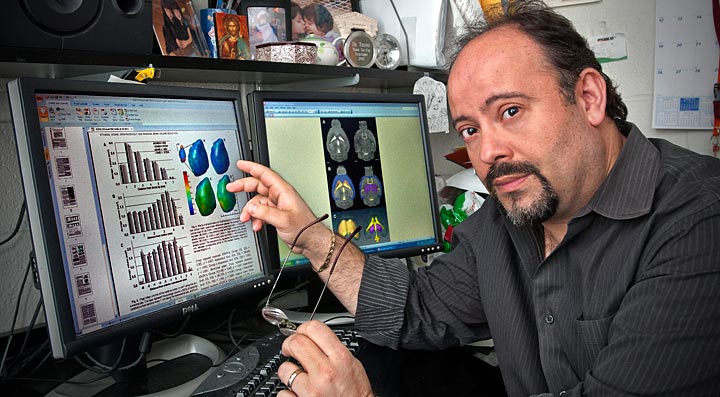

"There's a lot of public interest in health and longevity, but we really don't have a good handle on the mechanism of why certain individuals may live longer while others don't — and how this relates to certain genetic variants and lifestyles," said Panayotis Thanos, a neuroscientist in the Behavioral Pharmacology and Neuroimaging Lab at Brookhaven Lab. Thanos led the research along with Robert Moyzis at UC Irvine, and Nora Volkow, a psychiatrist who conducts research at Brookhaven Lab and is also the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

"We obviously expect genetic variants to play a role, so we looked at the effect of the interaction of specific genetic variants associated with active personality traits on longevity," Thanos said.

Thanos and his team studied a personality-modifying dopamine gene in a group of 1,151 individuals between 90 and 109 years old. This genetic variant - a derivative of a dopamine-receptor gene (the DRD4 7R allele) - appears at significantly higher rates in individuals over the age of 90, and is linked to lifespan increases in mice. The participants were part of the Leisure World Cohort Study, established in 1981 as a health survey among residents of the Leisure World retirement community in Laguna Woods, CA.

Beginning in 2003, 233 surviving participants over 90 years old from the Leisure World cohort were surveyed and genotyped at the human dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) gene and compared to a European ancestry-matched control population.

The DRD4 gene is known to regulate traits such as motivation and thrill seeking, and is also associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and addictive and risky behavior. More than 90 percent of people have a DRD4 gene with groups of alleles repeated 2, 4, or 7 times, and that variation could be the difference that enables a person to live past the age of 90.

This "oldest-old" population had a 66 percent increase in individuals carrying the 7R allele relative to the younger control group (aged 7 to 45), and the presence of the 7R allele was strongly correlated with increased levels of physical activity. Thanos' team also found that the DRD4 gene plays a role in protecting against dementia.

"We found an association between exercise and protection from dementia, but only for DRD4 7R subjects," he said. High levels of activity were correlated with much lower-than-expected prevalence of dementia, while low activity rates were correlated with far higher prevalence than expected. "This suggests that individuals with the DRD4 7R variant may be more sensitive to both the beneficial effects of activity as well as the detrimental consequences of inactivity," Thanos said.

These findings were further supported in laboratory experiments on DRD4-knockout mice, which do not have the DRD4 gene. Thanos and his team compared environmental effects on the lifespan of these mice to those of mice with DRD4 genes. Two types of housing environments were used - a standard laboratory environment, and an enriched environment that included social interaction with multiple options for physical activity and exploration.

In line with the findings in the human population, mice without the DRD4 gene had a 7 to 9.7 percent shorter lifespan than mice with the gene. They also found that mice in enriched environments lived 5.7 percent longer than mice in deprived environments, but only if the DRD4 gene was present.

"The human and animal data support each other, they match up so beautifully," Thanos said. "This is a very interesting gene-environment interaction. We know that lifestyle changes can have tremendous impact on lifespan and, as we see here, the interaction of specific lifestyle changes and environment are also dependent on specific genetic variants."

The research was funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Intramural Program.

2013-11481 | INT/EXT | Newsroom