AGEP-T FRAME Scientist Raul Acevedo Studies How Fuel Cells Behave in Space

March 1, 2017

As a kid growing up in Puerto Rico, Raul Acevedo was excited to learn from Carl Sagan’s Cosmos television show that the biggest radio telescope in the world was located on his island. The knowledge further stimulated his interest in astronomy and space. Later, a talk by an alumni from his high school who became a NASA engineer at the Alpha Space Station – now the International Space Station – allowed him to dream of a similar career in space science. That dream led him to pursue a Ph.D. in chemical physics from the University of Puerto Rico, where he received a NASA Space Grant fellowship to study the effects of microgravity on the electrochemical oxidation of ammonia in a fuel cell.

Now, Acevedo is a post-doctoral fellow in the Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate - Transformation (AGEP-T) Frontiers of Research and Academic Models of Excellence of Research and Academic Models of Excellence (FRAME) program at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory. The program capitalizes on research accomplishments at Brookhaven Lab and Stony Brook University to help underrepresented minority graduate students and postdocs develop the essential skills for success in intensive academic environments.

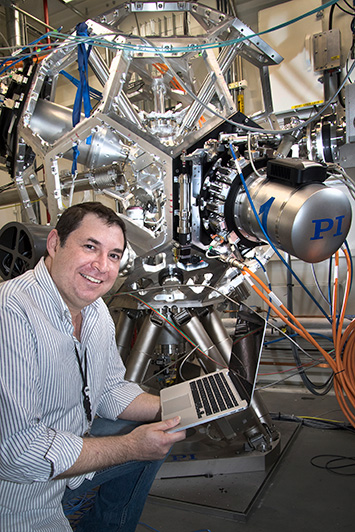

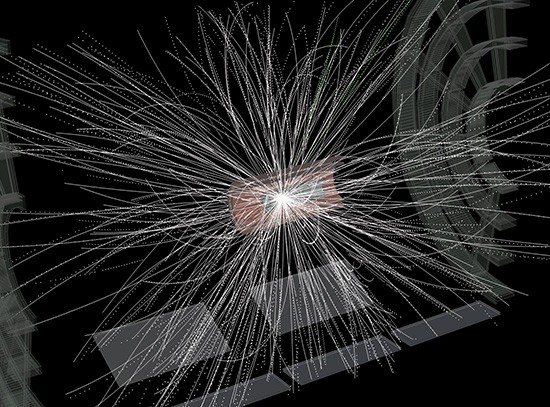

Since his arrival at Brookhaven Lab in August, Acevedo has been working at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, to develop a platform to work with fuel cells. This platform will be useful to analyze nanomaterials that work as catalysts.

“I can study them in the beamline in “operando” experiments—looking at the interfacial phenomena, the electronic and chemical changes that happen in the catalyst, as the electrochemical reaction happens,” said Acevedo. The research is conducted at the Inner Shell Spectroscopy (ISS) beamline at NSLS-II.

This 2014 video documents a flight conducting experiments in microgravity by students from the University of Puerto Rico - Río Piedras.

Acevedo has had considerable personal experience with space science, having flown eight times during his graduate studies on the so-called “vomit comet,” a plane that flies to 34,000 feet in an arc that allows it to achieve microgravity at 0.02 G, where gravity is effectively cancelled.

“The pilot does a maneuver called a parabolic trajectory, so for 30 seconds you can float like you’re in space,” he said. “During this time, we ran our experiments to see how microgravity affects our fuel cell. It’s a fast and cheap way of testing before actually sending materials to the Space Station. To send anything into space costs between $10,000 and $17,000 per pound, and one gallon of water weighs 8.3 lbs. At the Space Station, they want to recycle the water; they don’t want to waste anything.”

Eventually fuel cells could be used in the Space Station’s water purification system. The system will separate the toxic contents of urine from pure water so the waste can be used to power an alkaline fuel cell.

“It’s a win-win situation where you can take some waste and convert it into electricity,” Acevedo said.

He said he is often asked what it’s like to achieve weightlessness.

“It’s interesting because when you start floating, you don’t feel anything because you don’t move unless you push yourself against something fixed,” he said. “But then you see other people floating and then you start moving around. It’s like when you’re at the peak of a roller coaster, that’s where you start floating. The first two or three parabolas, it’s kind of hard. That’s why they call it the vomit comet, if you go with a full stomach, gravity does a trick with you. And when the 30 seconds are up, you have to be feet down because if not you will land on your head.”

Acevedo took a somewhat circuitous route to his present field of study. After earning his bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering, he spent time working in environmental and pharmaceutical compliance for the pharmaceutical industry. While working as a consultant providing services in Fort Worth, Texas, he visited the local science museum, which reignited his passion for science.

“That was the moment that I decided to come back and get my PhD in chemical physics,” he said.

Back at the University of Puerto Rico, Acevedo studied with Carlos Cabrera, an electrochemist working with NASA on materials used as catalysts for fuel cells. Acevedo became team leader for three microgravity experiment campaigns at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

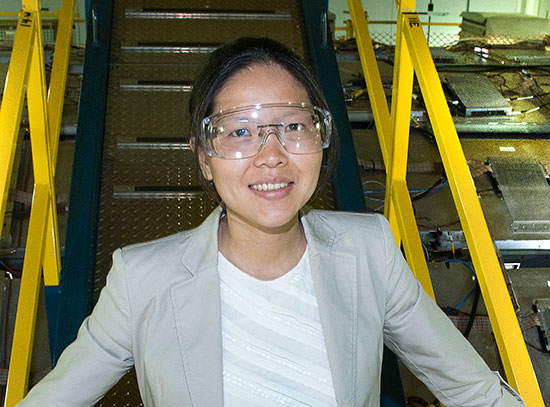

A visit to the University of Puerto Rico by Noel Blackburn of Brookhaven’s Office of Educational Programs and Nina Maung and Karian Wright from the Center for Inclusive Education at Stony Brook acquainted Acevedo with the AGEP-T FRAME program. When Brookhaven’s Qun Shen gave a talk at the university’s new molecular sciences building, Acevedo learned about the capabilities of NSLS-II. Both the program and the facility seemed like a good fit for his fuel cell work. Terrence Buck, who manages Brookhaven’s AGEP T-FRAME program, was also instrumental in recruiting Acevedo.

Acevedo has been very favorably impressed with Brookhaven Lab.

“It’s like being at a university but at the same time it’s a fast-paced environment where we are not just doing science for ourselves, we are also serving users,” he said. “I work with physicist Klaus Attenkofer and chemist Eli Staviski and I feel fortunate to have mentoring on both sides. There is a really interesting bunch of people here that I can learn from, with more than 100 years of experience altogether—and they have been very open to helping me.”

Acevedo, whose hobby is tinkering with the electronics of guitars, currently lives with his wife in Coram and has a 13-year-old daughter attending junior high school. Despite the shock of Long Island’s abundant snow – not a feature of the weather in Puerto Rico — he enjoys working at Brookhaven.

“Since I am an engineer, a chemist, and a physicist, there are many things that I can work with here, either tinkering with fuel cells or with the catalysts at the beamline,” he said. “This is a very important moment in the history of this beamline, as what is being done here is cutting-edge, world-class science. I have been able to serve as operator of the beamline and the intention is that I will be running my experiment and also giving support to users. That will give me an opportunity to discuss many different kinds of experiments beyond the boundaries of just catalysis and fuel cells.”

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

2017-12088 | INT/EXT | Newsroom