Pressure Transforms a Semiconductor into a New State of Matter

December 11, 2013

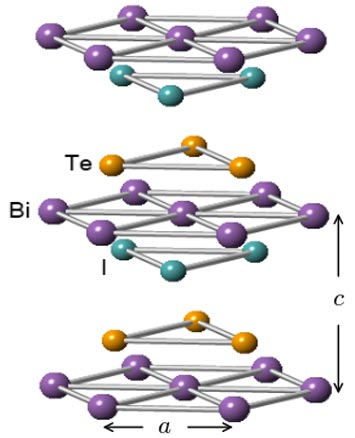

Crystal structure of bismuth-tellurium-iodine (BiTeI) semiconductor, with unit cell lengths labeled a and c

By applying pressure to a semiconductor, researchers have been able to transform a semiconductor into a “topological insulator” (TI), an intriguing state of matter in which a material’s interior is insulating but its surfaces or edges are conducting with unique electrical properties. This is the first time that researchers have used pressure to gradually “tune” a material into the TI state; as such, the study gives scientists a new route for discovery as they search for TIs that could be used in advanced electronics applications.

The group reports their results in the October 8 online edition of Physical Review Letters. The experiment was performed at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), with the transition into the TI state confirmed using beams of x-rays and infrared light.

“Despite the well-known underlying physics of topological insulators, expanding the topological material family remains a challenge,” said Brookhaven Lab Research Associate Xiaoxiang Xi, the paper’s lead author. “Our experiment indicates that pressure is an effective way to induce the topological insulating phase, and also that these techniques are useful for investigating the phase transitions that transform ordinary insulators into TIs.”

In a TI material, the bulk interior cannot conduct, but the surfaces or edges, referred to as boundaries, contain electrons that are “locked” into a special arrangement of their spins (spin is the property of an electron that gives rise to magnetism). This spin structure is a result of the symmetry-protected metallic state in which electrons flow freely with little scattering and virtually no mass.

The semiconductor used in this study is a compound of bismuth, tellurium, and iodine (BiTeI). In similar compounds, researchers have induced the TI state either by doping (adding a small amount of an extra element) or by growing a sample on a substrate selected to introduce structural strain – and therefore slight structural changes – in the sample during the growth process. Both of these methods produce the necessary changes in electronic behavior that allow a material to behave as a TI. Both methods lead to other problems, however. Doping tends to induce defects and inhomogeneities in the sample, while the substrate-induced strain method does not allow researchers to continuously tune and controllably study the material and process that transforms an ordinary insulator into a TI.

Using pressure avoids these drawbacks. At NSLS, the researchers applied pressure to a BiTeI sample up to about 10 gigapascals (GPa), which is roughly equal to 100,000 times atmospheric pressure. They tracked the structural and electronic changes in the material using two synchrotron techniques, x-ray powder diffraction and infrared spectroscopy, performed at NSLS beamlines X17C and U2A, respectively. The analysis revealed that BiTeI transitions into a TI in the pressure range from 2 to 8 GPa.

The x-ray diffraction patterns show that the BiTeI crystal unit cell, the basic building block of the crystal (with lengths that are commonly denoted a, b, and c), undergoes a small, but telling, change between 2 and 2.9 GPa: The ratio of two of the lengths of the unit cell, c/a, reaches a minimum value. This indicates a strengthening of the bonding along the c direction – an expected change during the transition in this material.

The infrared data also show a key feature over the same pressure range: a maximum in the “plasma frequency,” a quantity intimately related to the electronic structure and transport properties of the material. This feature is also something that is expected during a pressure-induced transition to the TI phase. It indicates that the BiTeI semiconducting energy gap – which normally prevents electrons in the material from participating in conduction – does close up and reopen as the pressure is swept through the transition region.

“The infrared feature is expected to be universal in pressure-induced topological phase transitions,” says Xi. “Thus, we expect that infrared spectroscopy will be useful for investigating other candidate pressure-induced TIs that have been proposed by theory.”

The other collaborators on this study include scientists from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Jilin University (China), Stony Brook University, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Florida.

The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

2013-4481 | INT/EXT | Newsroom