Epilepsy Drug Found to Stop Cocaine's Effects in Animals

Stops Brain Chemical Linked to "High"

August 5, 1998

UPTON, NY - An inexpensive epilepsy drug may prove to be a highly effective pharmaceutical treatment for cocaine addiction. In addition, preliminary data suggests that it may be useful for the treatment of other addictions.

That is the conclusion of animal studies published today in the journal Synapse by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and their colleagues from St. John's University, New York University, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Boston University.

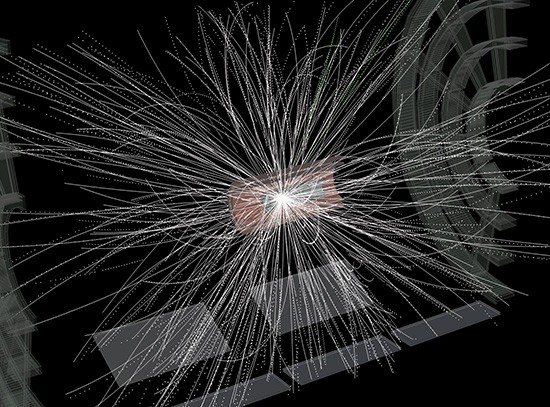

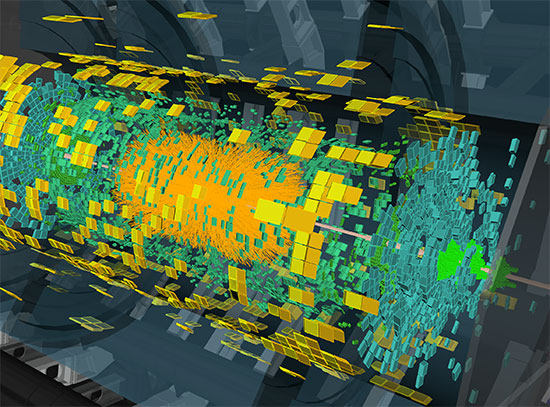

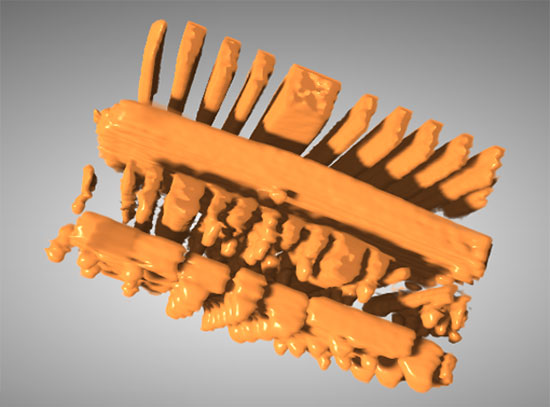

The team showed that the epilepsy drug gamma vinyl-GABA, or GVG, blocked cocaine's effect in the brains of primates, including the process that causes a "high" feeling in humans.

GVG also significantly decreased the amount of time that rodents spent in areas where they had previously received cocaine. Such behavior is important in human drug addiction.

But GVG did not stop animals' routine functions such as learning, eating and moving; nor did it cause other obvious side effects.

"We are extremely excited about our results," said Stephen Dewey, the BNL neuroanatomist who led the research team. "After all, more than a decade of hard work went into these findings. If this can do for humans what it did for animals, we may have opened the door for addicts around the world to kick their habit and for society to stop the costly cycle of addiction, violence and wasted lives. My colleagues and I are unaware of any other drug that has looked as promising."

Later this year, Brookhaven and NYU plan to begin a clinical trial to test GVG's effect on volunteer human cocaine addicts. Other institutions are also planning clinical trials.

The animal research was sponsored by DOE's Office of Energy Research and the National Institute of Mental Health, with involvement by the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

"The Clinton Administration's war against drugs is being fought on all fronts - not just in the streets but in the laboratory as well," said Acting Energy Secretary Elizabeth Moler. "We want Americans to know that we've got the best scientific minds in the country working hard to halt the destruction of lives and communities caused by drug addiction. Today's announcement offers the thrilling prospect that we may be closing in on a major science-based victory."

"These exciting preclinical data point to a major new approach to developing medications for cocaine addiction," said NIDA Director Alan I. Leshner. "Since we have no medications for cocaine overdose or addiction now in our clinical toolbox, NIDA has declared developing anti-cocaine medicines our top priority."

"While other pharmaceutical approaches to treating cocaine addiction have shown promise in animals, there is currently no effective pharmacologic treatment for cocaine addiction in humans," said Dewey. "In fact, the limited number of drugs currently being investigated in human addicts may prove to be addictive in themselves, or create tolerance and withdrawal symptoms."

GVG's anti-cocaine effects, however, have been tested more extensively in animals than any of the previously reported drugs. The BNL-led team used a total of ten techniques, including state-of-the-art medical imaging and behavior studies, to confirm their result.

GVG was originally developed to treat epilepsy. It is already in use in Europe and Canada, where patients have been using it safely for several years. The Food & Drug Administration has reviewed its safety and effectiveness for potential use in treating epilepsy in the U.S. It is expected to receive final FDA approval for epilepsy use this fall.

Today's publication is the culmination of more than twelve years of investigation that started when Dewey and co-author Jonathan Brodie, a psychiatrist at NYU's School of Medicine, began to look at the way brain cells talk to one another, especially in those afflicted with the mental illness schizophrenia. "These studies resulted directly from our early efforts to develop new treatment strategies for schizophrenia," Dewey said.

As the research progressed, Dewey and his colleagues realized that GVG might be useful in the treatment of drug addiction. They tested their surprising hypothesis over the past several years, and arrived at the conclusions published today in Synapse.

"Because cocaine addiction is part biochemistry and part behavior, these results confirm that it is possible to attack it on both fronts," said Charles Ashby, the St. John's University researcher who led the behavioral component of the study.

"One must always be cautious, however," said Brodie. "A serious clinical investigation is the logical consequence to this most exciting preclinical work."

Now," said Dewey, "the challenge is to see if GVG has the same effect on other addictions that involve the same set of neurotransmitters."

1998-10859 | INT/EXT | Newsroom