Miniature 'Wearable' PET Scanner Ready for Use

New tool will allow integrated, simultaneous study of behavior and brain function in animals

March 13, 2011

UPTON, NY — Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, Stony Brook University, and collaborators have demonstrated the efficacy of a “wearable,” portable PET scanner they’ve developed for rats. The device will give neuroscientists a new tool for simultaneously studying brain function and behavior in fully awake, moving animals.

The researchers describe the tool and validation studies in the April 2011 issue of Nature Methods.

Scientists from BNL, Stony Brook University, and collaborators have demonstrated the efficacy of a "wearable," portable PET scanner they've developed for rats. The device will give neuroscientists a new tool for simultaneously studying brain function and behavior in fully awake, moving animals.

“Positron emission tomography (PET) is a powerful tool for studying the molecular processes that occur in the brain,” said Paul Vaska, head of PET physics at Brookhaven with an adjunct appointment at Stony Brook, who led the development of the portable scanner together with Brookhaven colleagues David Schlyer and Craig Woody. PET studies in animals at Brookhaven and elsewhere have helped to uncover the molecular underpinnings of conditions such as drug addiction.

But studying animals with PET has required general anesthesia or other methods to immobilize the animals. “Immobilization and anesthesia make it impossible to simultaneously study neurochemistry and the animals’ behavior — the actions resulting from what goes on in the brain,” Schlyer said. “Our approach was to eliminate the need for restraint by developing a PET scanner that would move with the animal, thus opening up the possibility of directly correlating the imaging data with behavioral data acquired at the same time.”

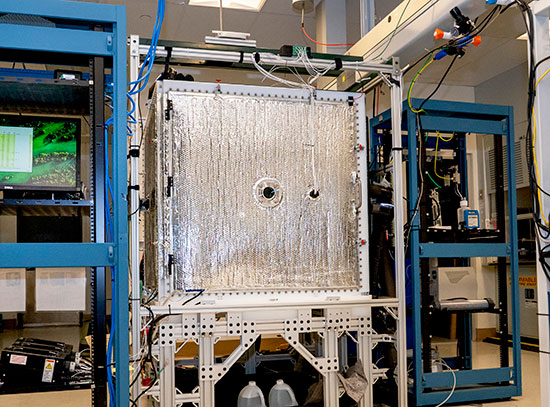

After several years of development, the scientists have arrived at a design for a miniature, portable, donut-shaped PET scanner that can be “worn” like a collar on a rat’s head for simultaneous studies of brain function and behavior. Weighing only 250 grams, the device — dubbed RatCAP, for Rat Conscious Animal PET — is counterbalanced by a system of springs and motion stabilizers to allow the animal significant freedom of movement. Measurements of the rats’ stress hormones indicated only moderate and temporary increases.

enlarge

enlarge

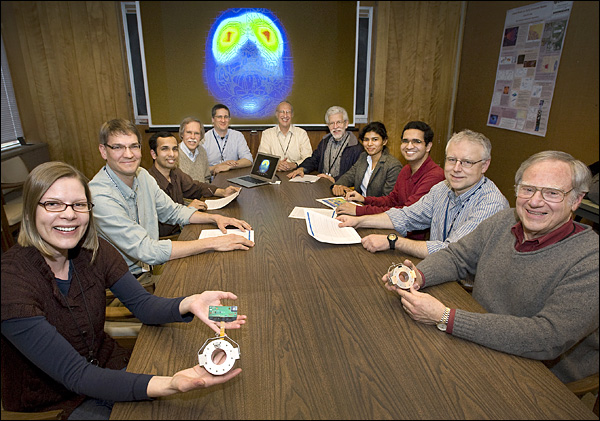

The RatCAP research team includes: Daniela Schulz, Paul Vaska, Srilalan Krishnamoorthy, Craig Woody, Sean Stoll, Fritz Henn, Paul O'Connor, Bosky Ravindranath, Sri Harsha Maramraju, Martin Purschke, and David J. Schlyer.

“Rats wearing the device appear to adapt well and move freely about their environment,” Woody said.

To validate the use of the wearable scanner for simultaneous studies of brain function and behavior, the scientists conducted tests with 11C-raclopride, a commonly used PET radiotracer, which incorporates a radioactive, positron-emitting isotope of the element carbon. When the positrons interact with electrons in ordinary matter, they immediately annihilate one another, emitting back-to-back gamma rays. Detectors in the circular PET scanner pick up the signals from these back-to-back gamma rays to identify the location and concentration of the tracer in the body.

enlarge

enlarge

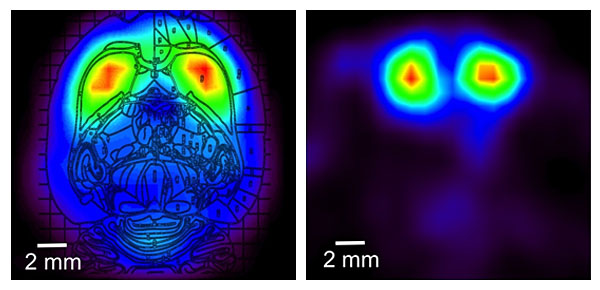

PET scans of a rat's brain made with the RatCAP scanner (horizontal view superimposed on a rat brain atlas figure, left, and a coronal slice, right). The rainbow scale (red = high, violet = low) indicates the level of a radiotracer that binds to receptors for dopamine, which are concentrated in the striatum, a brain region involved in reward and motivation.

The tracer 11C-raclopride binds to receptors for dopamine, a brain chemical involved in movement, reward, and memory formation. A higher signal from the tracer means that less natural dopamine is in that particular part of the brain; a low signal indicates that that particular part of the brain has released dopamine (which binds to its receptors, thus blocking the tracer from binding).

The main test was to see if the wearable scanner could be used to correlate dopamine levels with behavior — in this case, the rats’ activity (i.e., movement) within their chambers. Surprisingly the level of activity was inversely related to dopamine levels — that is, the more active the animals were, the lower the level of dopamine (as indicated by a stronger tracer signal).

enlarge

enlarge

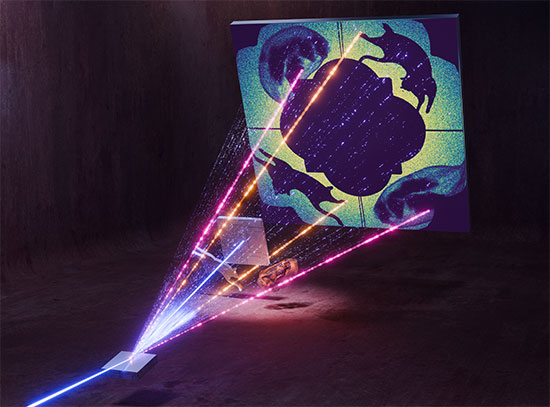

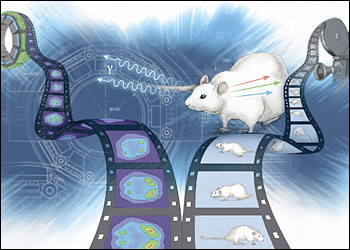

The sketch represents RatCAP's ability to simultaneously acquire information about brain chemistry, through PET scans (which track gamma rays produced as positrons from the radiotracer are annihilated by electrons in the body), and behavior, through classical video monitoring (which captures visible light images of animals in motion).

“This is perhaps a counterintuitive result because behavioral activation is typically associated with an increase in dopamine release,” said Daniela Schulz, a Brookhaven behavioral neuroscientist and lead author of the paper. “So our method provides data which may challenge traditional paradigms and ultimately improve our understanding of the dopamine system.”

“But regardless of the direction, the results clearly demonstrate that RatCAP can correlate brain function measurements with behavioral measures in a useful way,” she said.

The scientists also present results comparing RatCAP-wearing rats moving freely about their cages with animals that had been anesthetized, as well as comparisons of two methods of administering the tracer — injecting it all at once and in a steady infusion to maintain a constant concentration in the blood.

“These measurements will help us further refine the technique and aid in our assessment of results obtained with RatCAP in comparison with other study techniques,” Schulz said.

The researchers’ next step will be to use RatCAP to explore distinct behavioral expressions that can be correlated with simultaneously acquired PET data.

The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science. Development of RatCAP was a joint effort between Brookhaven’s Medical, Chemistry and Physics Departments, Instrumentation Division and the Biomedical Engineering Department at Stony Brook University. Co-authors on the paper include: Daniela Schulz (Brookhaven), Sudeepti Southekal (Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston),Sachin S. Junnarkar (Brookhaven), Jean-François Pratte (Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada), Martin L. Purschke (Brookhaven), Paul O’Connor (Brookhaven), Sean P. Stoll (Brookhaven), Bosky Ravindranath (Stony Brook), Sri Harsha Maramraju (Stony Brook), Srilalan Krishnamoorthy (Stony Brook), Fritz A. Henn (Brookhaven and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), Craig L. Woody (Brookhaven), and David J. Schlyer and Paul Vaska (Brookhaven and Stony Brook).

All research involving laboratory animals at Brookhaven National Laboratory is conducted under the jurisdiction of the Lab’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in compliance with the Public Heath Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal Welfare Act, and the National Academy of Sciences’ Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This research has enhanced understanding of a wide array of human medical conditions including cancer, drug addiction, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and normal aging and has led to the development of several promising treatment strategies.

2011-11235 | INT/EXT | Newsroom