Armored Caterpillar Could Inspire New Body Armor

June 8, 2012

The following news release is being issued today by the University of California, Riverside.

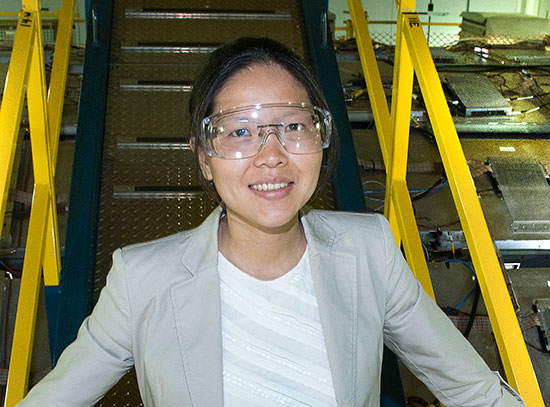

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory played key roles in this experiment, using beamlines at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) to reveal the composition and structure of the mantis shrimp club. Physicists Elaine DiMasi and Kenneth Evans-Lutterodt performed x-ray diffraction experiments at two NSLS beamlines, combining expertise in high-throughput methods with high spatial resolution techniques to map the intricately structured samples on the whole-organ (millimeter) and fine-grained (micrometer) scales. The results provided crucial details about the multi-tiered structure of the biological “hammer,” from the hard, crystallized minerals of the impact surface down to the underlying, shock-absorbing matrix of fibrous chitin, a complex sugar.

The micro-diffraction instrument used in this experiment is not available commercially and owes its assembly to efforts by Brookhaven Lab’s Rick Greene, Gary Nintzel, and the recently retired Shu Cheung and Tony Lenhard.

For more information about Brookhaven’s role, contact Justin Eure, jeure@bnl.gov, 631-344-2347, or Peter Genzer, genzer@bnl.gov, 631-344-3174.

University of California, Riverside Media Contact: Sean Nealon, sean.nealon@ucr.edu, (951) 827-1287.

enlarge

enlarge

A mantis shrimp shows off its fist-like clubs, which can accelerate underwater faster than a 22-caliber bullet. Photo credit: Silke Baron.

RIVERSIDE, Calif. (www.ucr.edu) — Military body armor and vehicle and aircraft frames could be transformed by incorporating the unique structure of the club-like arm of a crustacean that looks like an armored caterpillar, according to findings by a team of researchers at the University of California, Riverside’s Bourns College of Engineering and elsewhere published online today (June 8) in the journal Science.

The bright orange fist-like club of the mantis shrimp, or stomatopod, a 4-inch long crustacean found in tropical waters, accelerates underwater faster than a 22-caliber bullet. Repeated blows can destroy mollusk shells and crab exoskeletons, both of which have been studied for decades for their impact-resistant qualities.

The power of the mantis shrimp is exciting, but David Kisailus, an assistant professor at the Bourns College of Engineering, and his collaborators, were interested in what enabled the club to withstand 50,000 high-velocity strikes on prey during its lifespan. Essentially, how does something withstand 50,000 bullet impacts?

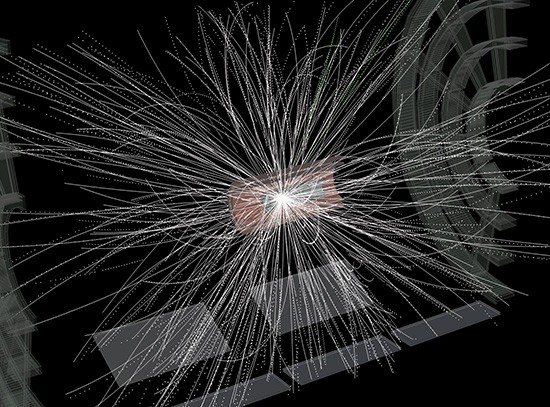

They found that the club is a highly complex structure, comprised of three specialized regions that work together to create a structure tougher than many engineered ceramics.

The first region, located at the impacting surface of the club, contains a high concentration of mineral, similar to that found in human bone, which supports the impact when the mantis shrimp strikes prey. Further inside, highly organized and rotated layers of chitin (a complex sugar) fibers dispersed in mineral act as a shock absorber, absorbing energy as stress waves pass through the club. Finally, the club is encapsulated on its sides by oriented chitin fibers, which wrap around the club, keeping it intact during these high velocity impacts.

“This club is stiff, yet it’s light-weight and tough, making it incredibly impact tolerant and interestingly, shock resistant,” Kisailus said. “That’s the holy grail for materials engineers.”

Kisailus said the potential applications in structural materials are widespread because the final product could be lighter weight and more impact resistant than existing products.

For example, with electric cars less weight will reduce power consumption and increase driving range. With airplanes, less weight would reduce fuel costs and better impact resistance would improve reliability and cut repair bills.

But Kisailus is primarily focused on improving military body armor, which can add 30 pounds to a service member’s load. His goal is to develop a material that is one-third the weight and thickness of existing body armor.

Kisailus and James C. Weaver, who worked with Kisailus as a post-doctoral scholar and is now at Harvard University, began work on the mantis shrimp when Kisailus arrived at UC Riverside in 2007. They were later joined at UC Riverside by Garrett W. Milliron, a Ph.D. student, and Steven Herrera, an undergraduate student.

Kisailus, who studies the structures of marine animals for inspiration to develop new materials, has also worked with snails such as the abalone and chiton, as well as sea urchin.

Those animals were all studied for their defensive prowess, in other words their exterior protection from predators. The club of the mantis shrimp interested Kisailus because it’s an offensive tool.

“We have been studying these other organisms when we should have been studying this guy because he literally eats them for breakfast,” Kisailus said.

The force created by the mantis shrimp’s impact is more than 1,000 times its own weight. It’s so powerful that Kisailus needs to keep it in a special aquarium in his lab so it doesn’t break the glass.

Also, the acceleration of the club creates cavitation, meaning it shears the water, literally boiling it, forming cavitation bubbles that implode, yielding a secondary impact on the mantis shrimp’s prey.

Kisailus and Pablo Zavattieri, of Purdue University, one of the co-authors of Science paper, just received additional $590,000 in funding from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research to continue work on the stomatopod. They want to further understand the structure of club and continue work designing materials inspired by that structure.

Since this project was multidisciplinary, Kisailus and his UC Riverside team continued working with Weaver after he moved on to Harvard University, and others including Ali Miserez, Nanyang Technical University in Singapore; Kenneth Evans-Lutterodt and Elaine DiMasi, Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, NY; and Brook Swanson, Gonzaga University.

“The team we put together was excellent: having experts in zoology, mechanics, modeling and synchrotron x-ray characterization gave us multiple views of the same problem, making it a very thorough investigation,” Kisailus said.

2012-11423 | INT/EXT | Newsroom