Operating Efficiently and Compliantly with Essala Lowe

interview with a CFN staff member

January 19, 2021

enlarge

enlarge

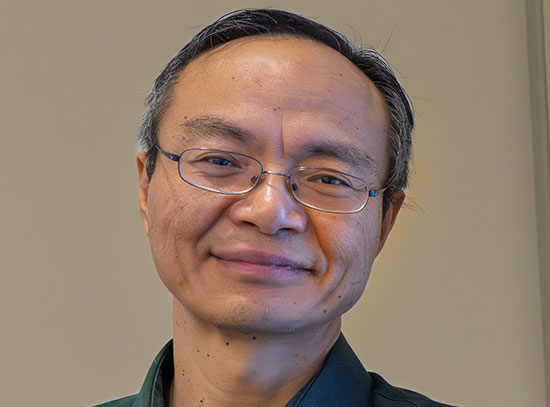

Essala Lowe outside Brookhaven Lab's Center for Functional Nanomaterials, where she is the assistant director of operations.

In May 2020, Essala Lowe joined the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN)—a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility at Brookhaven National Laboratory—as the assistant director of operations. In this leadership role, Lowe is responsible for overseeing day-to-day administrative and operational functions, ensuring the efficient, effective, and safe operations essential to CFN success. Lowe, a trained microbiologist, brings nearly two decades of experience in research administration, environmental health and safety regulatory compliance, and science operations at various academic and nonprofit institutions. She earned a master’s in public administration (MPA) with a concentration in nonprofit organizational leadership from Norwich University and a bachelor’s in psychology with a minor in biology and a postbaccalaureate certificate in environmental management from the University of Maryland.

You started your career as a microbiologist and then moved into research administration and operations. What prompted this transition?

Out of school, I became a quality control microbiologist. I loved working in the lab as a bench scientist. But my supervisors wanted to challenge me, so they kept giving me different projects, such as helping them build budgets or making sure we were being compliant in the lab. Through these projects, I realized that I very much enjoyed the business and operations sides of the lab. I come from a family of entrepreneurs—my grandmother and mother both owned businesses—so I think that the experience sparked the entrepreneurial spirit in me and segued me into research administration unknowingly.

In 2000, I started a position as the biosafety officer and Biosafety Level 3 facilities manager in the Department of Laboratory Safety and Environmental Health at Rockefeller University. This position kept me involved in science but also integrated regulatory compliance, safety, and program management. It merged the two things that I love: science and operations.

How has your time as a bench scientist impacted the way you go about operations?

In my opinion, there’s a theoretical and applied science to research operations and administration. It not only takes a business mind but also a science mind. You need an understanding of the science in order to understand how to best support it, especially when it comes to the financial and operational sides. Depending on the science or research goals, the support needed may be completely different.

I can still go into the lab and do assays and other techniques. This excites me because in a way I can look at a protocol or proposal and understand exactly the steps that need to be taken. I can consider it from an end-user perspective, ensuring that the research goals are met while being mindful of the safety and compliance aspects. Sometimes, that’s a hard balance because there are no roadmaps when you’re trying to do cutting-edge research. Some of what we’re doing at the CFN, especially in this new COVID environment, is create as you go. A lot of collaboration is required between me, scientists, and support staff to make sure we’re doing everything we can to support the research while being safe and compliant.

Where did your career take you after your position at Rockefeller?

In 2004, I became the corporate and biosafety officer for the American Type Culture Collection, which was the premier bio repository in the country at the time. It was a pivotal time in my career. The terrorist attacks of September 11 and anthrax letter attacks had recently happened, so public, national, and research safety compliance efforts and regulatory standards were at an all-time restrictive level. To be in this position during this period, at the apex of the changes in research administration, helped me to bring some sensibility to how the end-user researchers were being reviewed by regulatory folks who had really never been in that world before. It was exciting to speak the languages of the regulators and researchers to help both sides understand each other better and come to a more balanced viewpoint.

In 2006, I became the environmental health and safety and compliance manager for Janelia Research Campus at Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). I was responsible for the regulatory compliance for research and environmental health and safety for the entire campus. Janelia was the first standalone campus for HHMI that was unaffiliated with a university. This was a great opportunity to work with some of the most innovative scientists in the world on new ideas in basic neuroscience research. In this position, creating a balance for new procedures became a part of my daily responsibilities as the interface with regulatory agencies and researchers.

In 2010, I moved to George Mason University, where I was the director of laboratory safety and environmental compliance. Since 2012 and before joining the CFN, I was the director of campus operations at Northern Virginia Community College. With six campuses and about 80,000 students, NOVA, as it’s abbreviated, is the largest educational institute in the state of Virginia. Working for the provost, I ran all of the nonacademic areas of Manassas Campus, the third-largest campus with more than 10,000 students and the STEM [science, technology, engineering, mathematics] campus for the college. This role included managing budgets, events, facilities, projects, construction, health and safety, and security, as well as communicating with external and internal stakeholders and serving as the liaison between the Manassas Campus and the college’s offices of financial and administrative services.

Coming from the world of academia and nonprofits to a national lab, how have the dynamics changed?

Research is research no matter what. I’ve dealt with regulatory institutions my entire career. Living and working in the DC area, I always knew about the national labs and have worked with the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and other sponsoring agencies.

What’s different is learning and understanding how operations work on the inside of the national lab system. That’s the challenge of the job. Internally, organizations can be very bureaucratic. My goal throughout my career has been to be as least bureaucratic as possible but to always be compliant. I look for ways to interpret the regulations or guidelines while still supporting the science at the highest level possible.

That’s where my expertise comes in, whether I’m helping the CFN or Brookhaven at large, as I serve on several groups and committees—including the Brookhaven COVID-19 Task Force, operations council, and Directorate of Chief Operating Officers group. Coming from the academic and nonprofit research world, I can help them see a different way to do things that is still compliant. Sometimes, organizations can take the regulations or guidelines too far, putting themselves into a hole. In these cases, the organizations have to pull back a little so that the science isn’t unnecessarily restricted.

In your experience, what’s the best approach to achieving a balance between science and regulations?

Having been a safety director, an operations director, and all my other roles has taught me that you have to consider things on a case-by-case basis. The best analogy I can use is one my grandmother taught me: know when to use a sledgehammer or a scalpel. In other words, sometimes you need different tools for different situations. And there’s a range of tools you can use in between the sledgehammer and scalpel. You have to apply appropriate mechanisms and systems for the specific regulations or guidelines.

How I operate is putting systems in place that are agile and can be expanded or reduced to address the particular issues or problems. Regulations and guidelines change all the time. So, we need to build a skeleton and be ready to make changes as necessary. Adaptability and agility are critical in research administration. Instead of worrying about “getting in trouble,” we need to create a systems approach that will help us to be adaptable and agile while staying in compliance without restricting the research.

For me, research operations is a proactive science. If you adopt a proactive mindset instead of a reactive one where you’re reacting out of fear, you’ll be able to address any new type of science.

Can you give some examples of how you’re working to achieve this balance in practice at the CFN?

Currently, most of my projects fall within the category of administrative controls, such as distributing work across the staff who report to me and ensuring that the support systems in place are working as efficiently as possible.

Over the past six months, I’ve been meeting with the CFN research group leaders to understand their needs. They are the basis for all of the science that our external users connect to, so ensuring that in-house operations work well is the first step. I’ve also been working with the CFN User Office team, who manages users requesting access to our tools on-site or remotely, and the CFN administrative team, who keeps everything running. Outside of the CFN, I’m regularly in touch with Brookhaven’s Business Services Directorate, Procurement and Property Management Division, and Facilities and Operations Directorate. One of the reasons I was brought in was to better connect the CFN to the Brookhaven system of support, facilitating and acting as a liaison for these relationships.

One of the next big items on my agenda is new instrument installations and space management at the CFN. We’re continuing to hire staff, but we can’t move past the building footprint right now. So, the question is, how can best use the lab and office spaces we do have? For the lab component, we’re looking at which equipment is actually being used. As a user facility, the CFN wants to increase user access to the best tools available. My team is setting up a system of key performance indicators to determine which equipment should be taken offline and replaced.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted how you go about your role?

Because I’m mostly working remotely—I’m still in the process of relocating from DC to Long Island, so I come to CFN about once a month for a week at a time—I’ve had to adapt how I do operations. I have a great operations team at the CFN who keeps me abreast of what’s going on. We stay in constant communication, and using video has helped a lot for conducting virtual building walkthroughs. In operations, many times we have to see a problem in order to address it.

Working with people is a critical component of your role as assistant director of operations at the CFN. Have your undergraduate studies in psychology helped in this regard, and what drew you toward psychology in the first place?

I’ve always been a people watcher. My dad was a preacher, my mom was an educator, and my grandmother owned a barbershop. So, I saw my dad dealing with people from a ministry perspective, my mom with parents and students from an educational perspective, and my grandmother with people in general from an everyday life perspective. As a kid, I used to hear a lot and found it so interesting.

Intrigued by psychology, when I was an undergrad, I enrolled in a black psychology class about the effects of American culture on the black psyche. After that class, I decided to take a few more psychology classes. These classes in understanding people have helped me in my management responsibilities over the years to oversee teams and approach people from an emotionally intelligent perspective.

Where does your passion for science and research stem from?

My mother will tell anyone that I was an inquisitive kid always dabbling in science. When outside playing or milling around, I was in love with nature—alive and not so much alive. I was the kid whose dad bought me the sea monkey aquarium pet (brine shrimp) I saw advertised on the back of my comic books, so I could see if it was actually “monkeys” or not. I was the kid who asked for a microscope for Christmas instead of Barbie Dolls. In the summers, whether I was at camp or visiting relatives, I was intrigued by all things nature—gross or not. Without any fear, I’d cut the bloodworms for fishing bait. I always wanted to know how living things worked. That’s what I think drew me toward biology.

During my high school and undergraduate years, science, and biology specifically, came easy to me. I started off on the pre-med track. I wanted to be a medical doctor because—this is funny but true—I wanted to be an OB/GYN like Bill Cosby on The Cosby Show. But then I took an invertebrate zoology class, and it blew my mind. I learned about all of the microbes and organisms that can either hurt or help our lives, and we don’t even see them with the naked eye. The only way to see them is under a microscope. This one class made me stay in biology but turned me away from applying to medical school. It whet my appetite for research and different career pathways in science.

That summer, I went to the University of Virginia for a summer research program, working with a professor studying the effects of a particular organism on pregnant Norwegian white rabbits. In school, I had learned basic lab techniques like preparing petri dishes, but now I was actually putting these techniques into practice for a real research project funded by an NIH grant. The professor only taught one class, so she was mostly a researcher. Working with her taught me that research could be your life. At the time, she was one of the few women I knew who was a principal investigator and the first African American female researcher I had ever met. She was instrumental in getting me to understand what the professional side of being a research scientist was all about. This experience solidified my desire to become a bench scientist.

To this day, microscopy, virology, and microbiology get me excited. I think that’s why working at the CFN in the realm of nanoscience is bringing me back to the beginning of why I loved science so much—things that are so small can have such a huge impact.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2021-17661 | INT/EXT | Newsroom