Light Accelerates Conductivity in Nature's 'Electric Grid'

Yale researchers discover that light is a surprising ally in fostering electronic activity within the earth's web of bacteria-generated nanowires

January 10, 2023

The following article, which was originally published by Yale University, describes how researchers investigated the relationship between light and the electrical conductivity of nanowire-producing bacteria. To understand the mechanism of photoconductivity in the nanowires, the team leveraged the Advanced Optical Spectroscopy and Microscopy facility at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN)—a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy experiments at CFN revealed how light initiates an ultrafast charge transfer between iron compounds in the protein-based nanowires, increasing electrical conductivity. For more information on Brookhaven’s role in this work, contact Stephanie Kossman (skossman@bnl.gov, 631-344-8671).

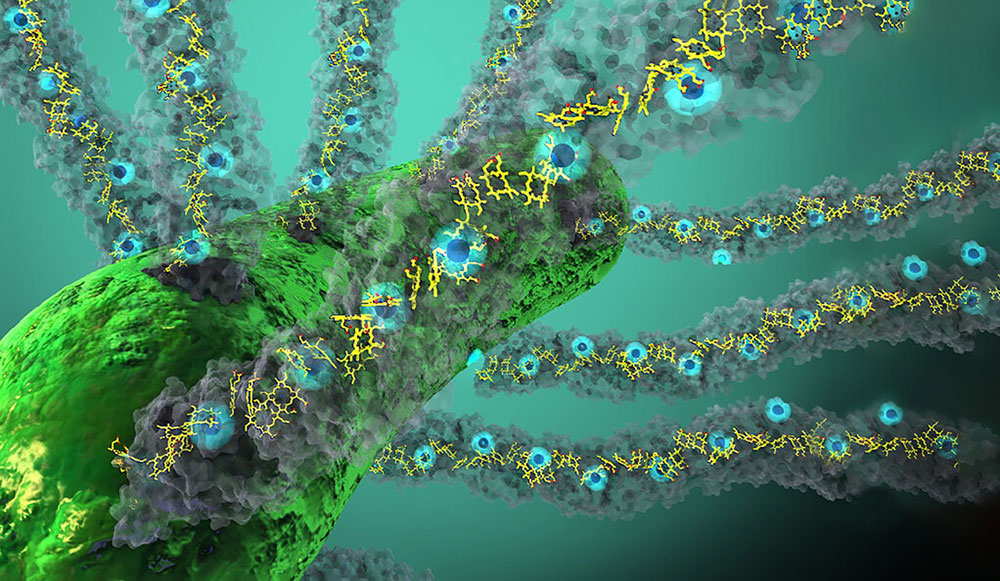

The natural world possesses its own intrinsic electrical grid composed of a global web of tiny bacteria-generated nanowires in the soil and oceans that “breathe” by exhaling excess electrons.

In a new study, Yale University researchers discovered that light is a surprising ally in fostering this electronic activity within biofilm bacteria. Exposing bacteria-produced nanowires to light, they found, yielded up to a 100-fold increase in electrical conductivity.

The findings were published Sept. 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

“The dramatic current increases in nanowires exposed to light show a stable and robust photocurrent that persists for hours,” said senior author Nikhil Malvankar, associate professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry (MBB) at Yale’s Microbial Sciences Institute on Yale’s West Campus.

The results could provide new insights as scientists pursue ways to exploit this hidden electrical current for a variety of purposes, from eliminating biohazard waste to creating new renewable fuel sources.

Almost all living things breathe oxygen to get rid of excess electrons when converting nutrients into energy. Without access to oxygen, however, soil bacteria living deep under oceans or buried underground over billions of years have developed a way to respire by “breathing minerals,” like snorkeling, through tiny protein filaments called nanowires.

When bacteria were exposed to light, the increase in electrical current surprised researchers because most of the bacteria tested exist deep in the soil, far from the reach of light. Previous studies had shown that when exposed to light nanowire-producing bacteria grew faster.

“Nobody knew how this happens,” Malvankar said.

In the new study, a Yale team led by postdoctoral researcher Jens Neu and graduate student Catharine Shipps concluded that a metal-containing protein known as cytochrome OmcS — which makes up bacterial nanowires — acts as a natural photoconductor: the nanowires greatly facilitate electron transfer when biofilms are exposed to light.

“It is a completely different form of photosynthesis,” Malvankar said. “Here, light is accelerating breathing by bacteria due to rapid electron transfer between nanowires.”

Malvankar’s lab is exploring how this insight into bacterial electrical conductivity could be used to spur growth in optoelectronics — a subfield of photonics that studies devices and systems that find and control light — and capture methane, a greenhouse gas known to be a significant contributor to global climate change.

Other authors of the paper are Matthew Guberman-Pfeffer, Cong Shen, Vishok Srikanth, Sibel Ebru Yalcin from the Malvankar Lab at Yale; Jacob Spies, Professor Gary Brudvig and Professor Victor Batista from the Yale Department of Chemistry; and Nathan Kirchhofer from Oxford Instruments.

2023-21040 | INT/EXT | Newsroom