From Hurricane Katrina Victim to Presidential Awardee: A SUNO Professor's Award-Winning Mentoring Efforts

A decade-plus collaboration between Brookhaven Lab and Southern University at New Orleans (SUNO) provides minority undergraduate students with hands-on opportunities to learn about natural resource management while developing the foundations for graduate studies

August 9, 2018

enlarge

enlarge

Southern University at New Orleans (SUNO) students (left to right) Chelsea Brown, Trevor McIntosh, Raven Williams, and Dulaine Vining with their biology professor, Murty Kambhampati (third from left), and Brookhaven Lab mentor, Timothy Green (third from right) of the Environmental Protection Division. Kambhampati has been bringing his undergraduate students to Brookhaven Lab to conduct field research in natural resource management. The Brookhaven Lab–SUNO collaboration began after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005.

After Hurricane Katrina struck the U.S. Gulf Coast in August 2005, an estimated 80 percent of New Orleans was under water, up to 20 feet deep in certain places. The flooding caused extensive damage not only to homes and businesses but also to college campuses in Katrina’s path. In the buildings of the Southern University at New Orleans (SUNO)—a small historically black university—flood waters rose six feet, forcing the campus to completely shut down. The nearly 160 full-time faculty members and approximately 3,650 minority students were just about to start their fall semester.

Educational impacts of Katrina

“Following Katrina, many of the faculty members were furloughed, and we lost 60 percent of the student population,” said Murty Kambhampati, a biology professor in SUNO’s Natural Sciences Department. “Those who remained for the fall semester were displaced to Southern University’s main campus in Baton Rouge, about 100 miles away.”

Financial burdens, housing displacement, and lack of transportation were among the reasons that student enrollment dropped so significantly. Kambhampati had been living in New Orleans at the time of Katrina but subsequently moved to Jackson, Mississippi, to temporarily stay at a friend’s home. Though the drive from Jackson to Baton Rouge normally takes three hours, it took seven hours post-Katrina.

For that semester, Kambhampati made the 14-hour roundtrip commute at least four days a week. Because the majority of students had dropped out of school, he spent much of his time writing grants.

His grant-writing efforts would later prove to be instrumental in acquiring nearly $7 million in funding to date from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), U.S. Department of Education (ED), National Science Foundation (NSF), and National Institutes of Health to support research, conference attendance, and other opportunities for his biology students. It would also lead to his 2015 Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring—the highest national mentoring award bestowed by the White House. Awardees are recognized for their outstanding mentoring efforts in encouraging the next generation of innovators and developing a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workforce that reflects the diverse talents of the United States.

“For the past 20 years, grants have been supporting my students,” said Kambhampati. “My main goal with this funding is to push minorities and women to advance their careers by extending their education beyond the bachelor’s degree level.”

Following Katrina, Kambhampati knew that he had to do something so that students would not miss out on opportunities crucial to their education and careers. In spring 2006, the faculty and students from the Baton Rouge campus were relocated back to New Orleans, where they were hosted by the Sophie B. Wright Charter School while cleanup and rebuilding efforts began at SUNO. It was at this time that Kambhampati applied for a research grant through DOE’s Faculty and Student Teams (FaST) program, now called the Visiting Faculty Program (VFP).

Sponsored and managed by the DOE Office of Science’s Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) in collaboration with DOE laboratories, this program seeks to increase the research competitiveness of faculty members and their students at institutions historically underrepresented in the research community, with the goal of expanding the workforce vital to DOE mission areas. Each of the 14 participating DOE laboratories offers different research opportunities, and colleges and universities are invited to submit applications on an annual basis for a 10-week summer appointment from May through August. Professors may invite up to two of their students to participate in the research.

Beginning of a long-term collaboration

Just before summer 2006, Kambhampati was attending the Annual National HBCU Conference, currently known as the Emerging Researchers National Conference. So was Noel Blackburn, who, as manager of university relations and DOE programs within the Office of Educational Programs (OEP) at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, is responsible for reaching out to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). But the two had never met. The day before the conference ended, Noel was trying to convince his colleague Joe Omojola, dean of the College of Science at SUNO, to come to Brookhaven Lab when he learned that Kambhampati had applied to the FaST program. Brookhaven was one of the participating DOE labs, with research opportunities in natural resource management.

“I knew Joe was doing physics so I thought he should come to Brookhaven Lab, but he said the person you really need to talk to is Dr. Kam,” said Blackburn. “Therein started a collaboration that continues today, 12 years later.”

That first summer, Kambhampati brought two of his biology students to conduct research at Brookhaven Lab.

During this time, Kambhampati also helped found the Interdisciplinary Consortium for Research and Educational Access in Science and Engineering (INCREASE). Formed at Brookhaven Lab and based at the HBCU Hampton University, INCREASE is a consortium of universities whose mission is to provide students at minority-serving institutions with access to world-class research facilities and tools. Its goal is to increase the number of women and individuals from historically underrepresented groups—mainly African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans—who pursue STEM careers.

“When I came to Brookhaven Lab in summer 2007, Noel said we need to collaborate in a much broader way,” said Kambhampati. “His idea led to the establishment of INCREASE.”

Through grants secured by Kambhampati and SUNO colleagues, INCREASE has supported workshops designed to introduce faculty to the capabilities of the National Synchrotron Light Source II and Center for Functional Nanomaterials—both DOE Office of Science User Facilities. These workshops, which are coordinated by Brookhaven Lab’s OEP, have played an important role in strengthening involvement among participating organizations.

Kambhampati has been returning to Brookhaven nearly every year thereafter, even after his three years of VFP participation, and has been bringing additional students to Brookhaven Lab each summer through the WDTS-sponsored Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI) program. Some of his students have also become interns through programs supported by Brookhaven Lab and external funding sources, including the College Research Teams Program (CRTP) and the Brookhaven Pre-Service Teachers Program (BPST). Over the years, he has brought as many as six of his students through these programs each summer. Five of his students are participating this summer.

An ideal site for ecological and wildlife research

All of the students conduct research under the mentorship of Timothy Green, environmental compliance section manager for the Environmental Protection Division and natural and cultural resource manager at Brookhaven Lab.

Located in a section of the chestnut oak forest region of the coastal plain of Long Island, New York, Brookhaven provides an ideal setting for diverse field experience in environmental science, ecology, natural resource management, and related disciplines. On site, more than 230 plant species have been identified, and 85 species of birds have been observed nesting. Brookhaven is also home to 10 species of fish—including the banded sunfish, a New York State (NYS) threatened species—and its ponds provide the largest habitat for the NYS-endangered eastern tiger salamander.

“Natural resource agencies are looking for individuals with relevant experience, which is really hard to get,” said Green, who hold a bachelor’s degree in wildlife science from West Texas A&M University, and master’s and PhD degrees in marine invertebrate zoology and freshwater aquatic invertebrates, respectively, from Texas A&M University.

Green has worked in natural resource management for the federal government since 1992—first as an outdoor recreation coordinator and then as the acting refuge manager at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and subsequently as a senior scientist at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas, where he grew up outdoors playing with lizards, snakes, and anything else he could get his hands on.

“My job is to ensure that Brookhaven abides by all the natural resource laws, and in order to do that, we need to understand ecosystems,” said Green. “Because I am not on the research staff and thus have no research budget, many of the projects to obtain this understanding are conducted with the assistance of summer interns, who collect information through natural resource investigations. The experience they acquire through these field research opportunities is really helpful in getting them into advanced STEM degree programs.”

A video providing an overview of the collaboration between Brookhaven Lab and Southern University at New Orleans.

Since the collaboration began 12 years ago, Kambhampati has brought 35 students to conduct research at Brookhaven Lab. Their projects have included testing metal and sediment concentrations in ponds, monitoring the reproduction of eastern tiger salamanders, and determining the effectiveness of devices that apply pesticides to white-tailed deer for the control of disease-carrying ticks.

In the early years of the collaboration, some of Kambhampati’s students worked alongside Vishal Shah, who was at the time an associate professor of microbiology and chair of the Biology Department at nearby Dowling College, to map the microbial community of the Long Island Pine Barrens by collecting soil samples. This mapping represented the first-ever fingerprint of a forest system, and the research—which was supported by DOE’s WDTS, NSF’s HBCU Undergraduate Program, and ED’s Minority Science and Engineering Improvement Program (MSEIP)—led to a publication in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE.

enlarge

enlarge

Jeffery Ambrose prepares soil pellets for microbial studies during his summer 2009 internship at Brookhaven Lab.

Jeffery Ambrose was one of the students who contributed to this research. “My time at Brookhaven inspired me to pursue a career in research,” said Ambrose, who spent two summers at Brookhaven Lab—one as a FaST intern in 2008 and another as a SULI intern in 2009. In 2008, he presented his research on plant biology at the annual HBCU Undergraduate Program National Research Conference, winning the first-place oral presentation award in the Ecology and Environmental Earth Sciences category. “I now hold a PhD in biomedical engineering and work as a manager at a well-known analytical laboratory, Eurofins.”

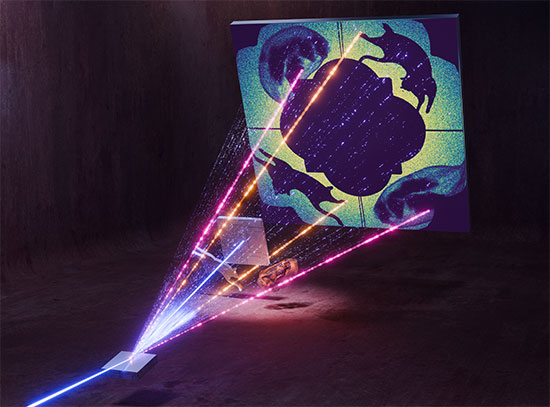

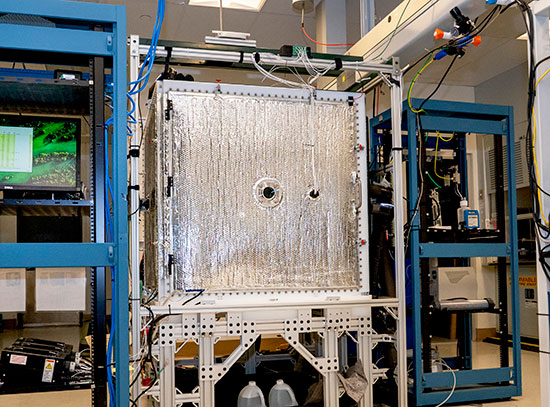

This summer, one of the projects is a follow-on one from last summer in which students are trying to understand how vegetation (as opposed to gravel or dirt) on solar farms is beneficial for pollinating insects such as bees. Brookhaven Lab is home to the largest photovoltaic solar power plant in the Eastern United States, and the students are establishing a program to monitor the different kinds of pollinating insects observed over the next few years.

2018 SULI intern Chelsea Brown—who is expected to graduate from SUNO in fall 2019—is one of the students involved in this project.

“I was attracted to this research topic because it is related to current national issues that need resolutions,” said Brown. “One in three bites of food that we eat is derived from plants pollinated by bees, whose populations are in decline, with some species declared endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. I learned how to survey the solar farm by collecting vegetation data on random rows of the farm using 50-meter transects and am collecting data for both vegetation and pollinators at 10-meter intervals along the transect. Conducting research at Brookhaven has expanded my outlook on the career opportunities associated with environmental science, and the techniques I learned will have an everlasting impact on my education and future endeavors. I am interested in becoming an ecologist focusing on conservation.”

Brown credits the tough times she faced in Katrina’s aftermath for giving her the ability to persevere: “When Katrina struck, I was 13 years old. My family and I lost our home and all of its contents, which were mildewed and not salvageable. We stayed in a hotel on Canal Street to seek shelter, and when the hotel ran out of food, it was apparent that no one was coming to rescue survivors. People were looting from the local Winn-Dixie supermarket and other stores. I was not able to attend school for almost two months because of relocation. It was the most frightful time I have ever lived through. I am blessed that I survived the natural disaster, and I know that if I can survive Katrina I can make it through anything.”

enlarge

enlarge

James Dempsey (fourth from left), facility manager of Brookhaven Lab's solar farm, with SUNO students (left to right) Dulaine Vining, Raven Williams, Chelsea Brown, and Trevor McIntosh prior to going to the experimental sites to collect vegetation and pollinator data.

Academic transformations

According to Kambhampati, these research projects not only provide the students with the scientific expertise they need for natural resource management but also build their self-esteem and confidence and change the manner in which they approach their schoolwork.

“Something as simple and nonscientific as successfully getting a bee into a collection vial can go a long way in boosting their confidence,” said Kambhampati. “Back on campus, they feel more at ease answering questions and interacting with their professors in the classroom and begin to explore other opportunities that will allow them to advance their skills. On average, SUNO students take six to six and a half years to graduate with a bachelor’s degree. By comparison, SUNO students enrolled in STEM programs like this one graduate two years sooner.”

Nearly half of the 35 students have gone on to pursue master’s or doctoral degrees, which have led to careers as research scientists, medical doctors, toxicologists, pharmacists, nurses, and science teachers. Several students have also won national recognition and awards.

“Nobody expects you to become a scientist where I’m from—a very small rural town outside of Houston, Texas—especially as a black woman,” said Octavia Allen, who enrolled in the biology program at SUNO in 2015 after securing a women’s basketball scholarship. “To be frank, no one really expects you to become much of anything.”

In summer 2017, Allen came to Brookhaven Lab with Kambhampati as a SULI program intern. For her project, she conducted an ecological study of the variations in the habitats and clutch sizes of eastern box turtles, which are the most common terrestrial turtles native to the Long Island Pine Barrens.

According to Allen, this experience was transformative: “I had no idea that there are so many national labs that welcome budding scientists to become a part of their team and help develop their skills. Being at Brookhaven Lab gave me an entirely new perspective on what research entails. I absorbed as much as I could from other scientists in various backgrounds, and I gained more confidence in reaching my career goals through hearing how these scientists got to where they are today. Dr. Kam, Dr. Blackburn, and Dr. Green had a profound impact on me not only as a scientist but also as a person. I’m encouraged that my journey is moving in the right direction.”

In May 2018, Allen graduated from SUNO with a bachelor’s degree in biology. Currently, she is at West Chester University (WCU) in Pennsylvania, conducting research on biofuel production from anaerobic microbes by wind-actuated bio-electrochemical systems. In the fall, she will begin her master’s program in biology at WCU.

For many of the students, their internships represented the first time they conducted research.

enlarge

enlarge

Left: SUNO student Raven Williams, who is studying biological science and mathematics, checks a trail camera used to record the number of white-tailed deer who visited a passive feeding station (called a four-poster device). Right: Williams programs the cameras to deploy in the field. For the past five years, Brookhaven Lab has been using these devices, which rub permethrin—a tickicide—onto the necks of the deer as they eat corn. With those devices installed at 14 locations on site, the Lab reduced the tick population by 90 percent. However, filling the posters with corn is time consuming and costly. Last year alone, the deer were fed 77,000 pounds of corn—an amount equivalent to more than $20,000. This summer, Williams is helping start a three-year experiment to see if the amount of corn could be reduced while continuing to effectively control the tick population.

“I had never done research or been to a national lab, so the internship at Brookhaven started off as a challenge,” said Precious Williams, a 2017 CRTP intern. “I had to learn how to use radio telemetry and to notch eastern box turtles in Brookhaven’s pine barrens to observe the relationship between the turtles’ behavior and weather conditions. Even though this research is not directly related to my career goal of becoming an emergency medicine physician, it helped me believe in myself and showed me that I can achieve anything with a little hard work.”

Carmen Maldonado—one of the first students to come to Brookhaven Lab with Kambhampati—expressed a similar sentiment.

“During summers 2007 and 2008 as a SULI intern, I was studying the banded sunfish population, and my mentors showed me what to do but then it was up to me to drive the project,” said Maldonado. “From then on, I wanted to incorporate research into some aspect of my career.”

Maldonado began as a freshman at SUNO—where her parents are alumni—the January following Katrina. It was in this first semester while taking one of Kambhampati’s courses that she was introduced to research.

“My home was flooded with four feet of water because of Katrina, but I was determined to go to school so I could pursue my dreams in the medical field,” said Maldonado. “Dr. Kam not only provided my classmates and I with many research opportunities but also advocated for and believed in us. My time at Brookhaven really solidified my interest in research, and the skills I learned have tremendously helped me throughout the rest of my education and in my career.”

In 2008, Maldonado received the National Role Model Award from Minority Access Incorporated. After graduating summa cum laude from SUNO in 2009, she went on to pursue a master’s degree in health policy and systems management at Louisiana State University, graduating cum laude in 2011. She then attended podiatry school at Temple University and finished her residency in New Orleans this past June.

“Even in my residency, I incorporated research,” said Maldonado. “I was able to hone in on my skills developed while at Brookhaven to look at quality metrics in the department, such as the major factors impacting patient readmission.”

A few weeks ago, Maldonado started a staff position at the Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans.

enlarge

enlarge

SUNO student and 2017 summer intern Precious Williams observes an eastern box turtle held by another intern. The students attached a radio transmitter to the turtle to study its behavior.

The students are not the only ones who benefit from the program. Kambhampati too gains from his time at Brookhaven Lab, bringing techniques or knowledge learned in the field back to the classroom to enhance his curriculum.

“I never thought I would end up in teaching,” said Kambhampati, who earned a PhD in ecology from Andhra University in his native India before enrolling in another PhD program in environmental sciences at Jackson State University in Mississippi. “My passion was research—I wanted to discover something that would help others. In a sense, I did, but not in the way I had originally envisioned. While pursuing my doctorate at Jackson State, one of the faculty invited me to participate in a NASA [National Aeronautics and Space Administration] outreach project for inner-city kids. We ended up getting a small two-year grant—the first funded grant that I helped develop in the United States. In 1994, I got a call from SUNO asking me to teach for the fall semester, and I thought, I am in a PhD program, I do not need a job. But, I reconsidered the offer and ended up accepting it. SUNO asked me to continue in the spring and then offered me a tenure-track position. It was at SUNO that I discovered how I could push women and minorities to take their education to the next level in order to advance their careers. It takes a lot of time and effort, on top of my teaching load, but it is very worthwhile.”

A work in progress

SUNO “reopened” for the fall 2007 semester, operating its administrative offices and classrooms out of trailers provided by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

“When I visited SUNO in spring 2007, Dr. Kam’s office was in the trunk of his car,” said Blackburn.

enlarge

enlarge

SUNO STEM faculty and students participating in research this summer gather outside the Old Science Building on the Southern University at New Orleans campus in May 2018.

SUNO infrastructure has come a long way since then. The trailers were decommissioned in December 2013 with the opening of a new multipurpose complex. However, the devastation caused by Katrina lingers today. The first floors of pre-Katrina buildings remain inaccessible, and the new science complex is still under construction, though it should be ready to occupy by next semester.

Student enrollment has improved—currently approximately 2,500 students attend SUNO—but has not been restored to pre-Katrina rates. Kambhampati and his colleagues have been trying to recruit students from neighboring high schools, but so are educators at Tulane, Loyola, and other nearby colleges devastated by Katrina. This competition makes recruitment difficult, but according to Kambhampati, one of the highest percentage increases in student enrollment among nearby colleges has been at SUNO.

“I believe this increase is due to the success of the students,” said Kambhampati. “Many of our graduates are going on to pursue advanced degrees.”

“I am so thankful that my professor chose me to participate in this research experience,” said Raven Williams, a 2018 CRTP intern and junior at SUNO. “Through my fieldwork, I have learned how to collect and analyze data using biostatistics—skills that will help me back at school with different research projects and increase my competitiveness when applying to graduate or dental school.”

For Brookhaven Lab, the collaboration with SUNO students has led to a basic understanding in many areas related to natural resource management that would not have otherwise been possible.

“The interns’ projects have real impacts,” said Green. “For example, we learned that our pine barrens—which are so-named because of their nutrient-poor soils—have low concentrations of nitrogen because bacteria in the soil immediately uptake and bind this element when rainwater hits the ground. Nitrogen is essential for plant growth and thus greatly contributes to the overall productivity of ecosystems. However, the lack of nitrogen is one of the reasons forests like the Long Island Pine Barrens are termed “barren.” We used Brookhaven Lab’s former National Synchrotron Light Source to identify which kinds of nitrogen were present and bound to soil particles.”

The Brookhaven Lab–SUNO collaboration also provides a “template” for how students can conduct research at a national lab.

“This collaboration has shown how to develop a very sustainable relationship between a university and a national lab,” said Blackburn. “I see it going on for many more years and leading to similar partnerships with other universities.”

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2018-12989 | INT/EXT | Newsroom