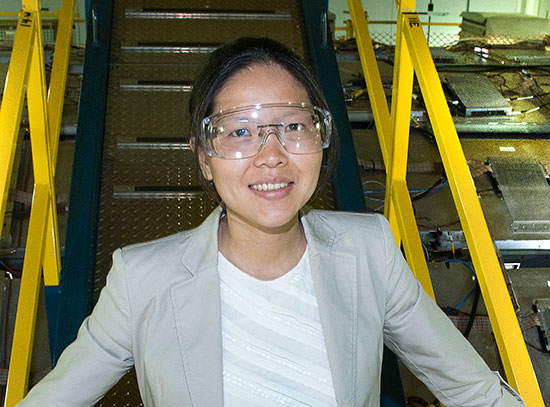

Q&A With Katherine Bachner: How intercultural awareness can improve science communication—from nuclear security to synchrotron science

April 15, 2016

Katherine Bachner, a scientific associate in the Non-proliferation and National Security Department at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, has traveled all over the world helping scientists and government officials understand how to communicate with one another. Her approaches have relevance for how all scientists engage with one another and the public to increase scientific understanding.

Q. You started out with an undergraduate degree in anthropology from Hartwick College and a Masters in cultural anthropology from Columbia University. How did that background lead to a career in non-proliferation and national security?

A. Well, after I finished at Columbia, I decided to travel to Mongolia to study Central Asian shamanism. Having a broad interest in world religions, I later participated as a post-graduate student in a religious studies study abroad program for university students in India. After India, I spent some time working on a goat dairy in Hawai’i, and then went back to upstate New York, where I was a goat milker on an organic farm. All of those were incredible experiences. But eventually I wanted to do more ambitious things and thrive in a more intellectual environment. I wanted to get involved with something that was international, something that crossed country borders. I also wanted something that would help people and keep me fascinated forever. I had always been interested in the Monterey Institute of International Studies in California, so I applied and decided to study international policy with certificates in non-proliferation and Russian studies.

Q. What is non-proliferation and what about it fascinates you?

A. Nuclear non-proliferation is the field of work, study, and policy that endeavors to prevent the further spread of nuclear weapons. Many in the community also see it as an important step on the path to nuclear disarmament (reducing and eliminating nuclear weapons). I was interested in studying non-proliferation not only from a policy perspective, but also taking into account how people’s different cultures influence their misunderstandings, which can contribute to the development of weapons programs. I was also interested in how understanding those cultural differences can help to improve non-proliferation and ultimately reduce the number of weapons.

Q. So, since you received your second masters in non-proliferation, what have you been doing to help countries increase their understanding of one another?

A. After studying at Monterey, I spent six months at the United Nations in Geneva and worked on various disarmament issues at the Conference on Disarmament. I learned a lot about the inner workings of treaty agreements, including the important lesson that it is not easy to get countries to agree on a treaty no matter how hard you work. From there, I was really lucky to be selected for a non-proliferation graduate fellowship at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) in Washington, D.C., where I started working on non-proliferation programs in the Russian Federation and former Soviet Union countries.

Q. You’ve been working as a scientific associate at Brookhaven Lab since 2011. What does your job here entail and how do you see it progressing in the future?

A. When I first came here I worked mainly on international nuclear safeguards engagement, which involves providing training on issues relevant to nuclear safeguards to countries that request it. Nuclear safeguards are part of what a nation signs up for when they join the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear weapons (NPT), and they basically are a system of tools that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) uses to confirm that no nuclear materials are unaccounted for, and that no undeclared nuclear activities are taking place in in states that are party to the treaty. I travelled to many countries and collaborated with various counterparts abroad as they improved their nuclear materials accounting systems and control over nuclear materials.

Nowadays, I work on a broad spectrum of issues that are tied together by being relevant to safeguards policy. One of my unique areas of expertise—at least in the national laboratory complex—is in the area of intercultural competency. Intercultural competency is having a cognitive framework to draw on that allows one to understand the under-the-surface drivers of behaviors that may be at work in intercultural exchanges, discussions, negotiations, and collaborations. This means, for example, that I can help people with a generally U.S.–centric mindset be a little more sensitive to cultural differences, so that when they work abroad or host people from other countries, they’ll build relationships with their counterparts abroad more effectively, smoothing the way for the success of their technical endeavors.

Q. You also work on the idea of “transparency.” What does that mean and how is it achieved?

A. Transparency is embracing openness and sharing knowledge related to technical and policy issues with stakeholders and other interested parties. An important part of this is avoiding unnecessary opacity. Another important part is making an effort to translate technical jargon into comprehensible, accessible language. This is critical when trying to help bridge the gap between scientists and the public to ultimately come to an agreement. With nuclear power, for example, to build a working relationship between citizens and the government or power authority, the organization spearheading the endeavor needs to be transparent about not only its intentions, but also any safety information that could be of interest to the public. There is a lot of fear when it comes to something like nuclear power and the more trust that is established, the easier it can become to work together toward a common goal, like clean energy. I’ve found that the biggest keys to being transparent with the public are knowing and understanding their concerns and making sure to continually engage with them by holding routine public meetings, or having a board or stakeholders association so that the public can be directly involved in all decisions. The bottom line is: know your audience, listen to their concerns, and tailor your message to their communication style so they can absorb and benefit from what you are saying. One of my current interests is in civilian nuclear transparency, which I recently wrote about to earn a diploma in international nuclear law from the University of Montpellier, France.

Q. It sounds like transparency has a lot to do with science communication in general. Could the idea of transparency help scientists in other fields?

A. I think all scientists can benefit from trying to see the utility in sharing their ideas more broadly. Part of the brilliance of scientists is that they are (often) thinking about the problems they are solving more than they are thinking about how to communicate those problems to the public or even to other scientists. I do a lot of work helping scientists understand different communication styles and training scientists to understand their counterparts’ behavior so they can communicate more effectively.

Q. What are some of the ways scientists can be more transparent, especially when it comes to energy?

A. We as a society are very much focused on the “now” and maybe one generation down. But do a lot of people think about five generations from now and what the world is going to look like for them? I don’t think so. I think that there could be a more constructive engagement between scientists and activists, and the public in general about sustainable energy sources like nuclear and how they could help offset our carbon emissions. It’s all about breaking down the walls between the ivory tower of science and the people that need it, that’s what needs to happen.

Q. From your perspective, how well do scientists at Brookhaven share their ideas with the surrounding public, and how do you think they could improve those initiatives?

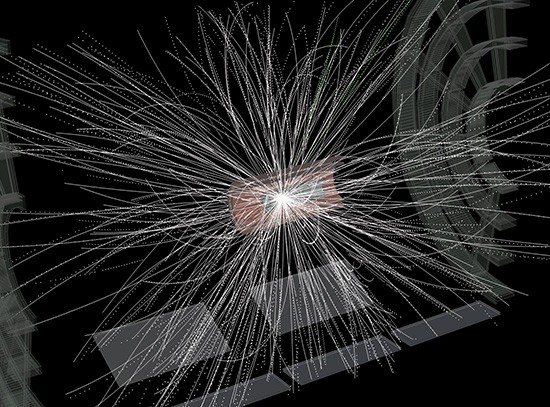

A. Brookhaven is doing a lot of really important work in cutting-edge sciences with state-of-the-art facilities like the National Synchrotron Light Source II, and other facilities. A lot of people here are very transparent and want to share their enthusiasm, but they need to practice explaining their research to people who don’t have the terminology in their everyday vocabulary. Likewise, the public should take up every opportunity that the Lab offers to engage with our scientists, such as Summer Sundays held multiple weeks during the summer, opportunities for kids, or the seminars held throughout the year that are open to the public. The Lab’s Community Advisory Council is another important venue where scientists and the public can exchange ideas. These programs help the Lab determine how the public is responding to our science, and they also help the scientists learn how to communicate their work better I also think it would be great for the Lab to continue increasing its visibility, to expand programs involving collaboration with the local community, and to strengthen our focus on understanding local and regional perspectives.

2016-6276 | INT/EXT | Newsroom