Brookhaven Lab Helps Develop Technology to Turn Dredged Material into Cement

April 7, 2004

EPA contact for this release: Nina Habib Spencer, (212) 637-3670, habib.nina@epamail.epa.gov .

Upton, NY - Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory have helped develop a new technology that converts material dredged from the bottoms of harbors and waterways into a substance that can be made into construction-grade cement. The technology, called Cement-Lock, was developed in collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the State of New Jersey, and other government and public groups.

"This technology will greatly help to increase the health of many U.S. harbors and waterways, such as the Port of New York and New Jersey," said Keith Jones, an environmental scientist at Brookhaven who took part in Cement-Lock's development. "These waterways are contaminated by metals and pollutants from many human activities, such as sewer overflow systems and discharges from industrial operations."

To ensure that the port can continue to service large container ships, which need deep water, it must be dredged regularly, Jones explained. But because the dredged material is contaminated, there are very strict restrictions on where and how it can be disposed of.

According to Eric Stern, the EPA Regional Contaminated Sediment Program Manager, "Sediment decontamination is a component of an overall dredged material/contaminated sediment management strategy. What sets this program apart from typical remediation is that beneficial use products - cement, lightweight aggregates, bricks, and soils - are the end result. These products then serve as economic drivers for the restoration and revitalization of impacted waterways, ports, and harbors around the entire world."

Brookhaven Lab has been involved in the development of sediment decontamination strategies since 1994, when it began collaborating on a decontamination program for the Port of New York and New Jersey, called the New York/New Jersey Harbor Sediment Decontamination Project, led by Stern. The collaboration also includes the EPA, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) Office of Maritime Resources, which joined the collaboration in 1998.

Many researchers at Brookhaven Lab participated in that project, and began by performing basic research on contamination chemistry. For example, the bright beams of x-rays produced at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven were used to closely study how contaminants in the sediment are distributed.

Brookhaven researchers also determined which experimental treatment methods would be tested and selected several technology companies to perform bench and pilot-scale tests, which can treat a few gallons and several cubic yards of sediment, respectively.

Once those test results were completed, the Brookhaven group reviewed the results and selected several treatment methods for full-scale demonstrations. As a result, Brookhaven and the EPA awarded contracts for the construction and operation of two large-scale sediment treatment facilities that can treat thousands of cubic yards of material. The Gas Technology Institute (GTI) in Des Plaines, Illinois, which developed Cement-Lock during the initial testing phases, is one of the two winning companies. GTI is an independent company that develops energy and environmental technologies.

"The GTI group developed a process that can treat all types of sediment, and highly contaminated ones, in particular," said Jones, who is also the project's technical manager. "The facility has potential for use on major problem spots in the region, including the Hudson and Passaic Rivers."

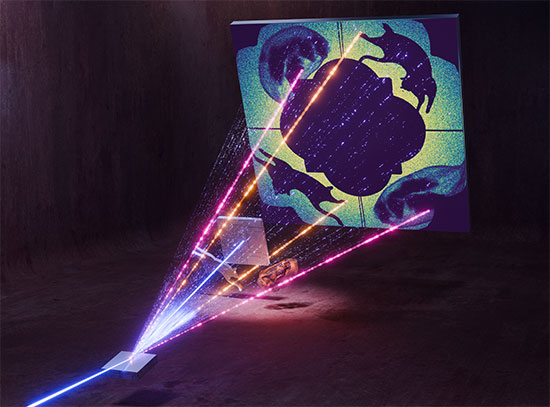

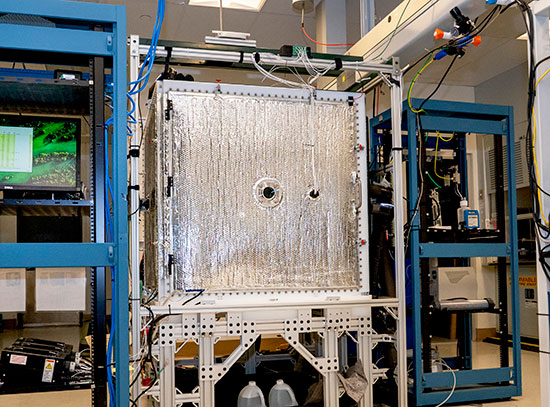

GTI is now carrying on a large-scale demonstration of the Cement-Lock process with a specially constructed 10-foot diameter by 30-foot long rotary kiln melter that they built for the demonstration in Bayonne. In the process, dredged material and modifying minerals are loaded into the kiln and heated to between 2,400 and 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit, creating a molten material. The high temperature causes some contaminants in the material to break down into environmentally safe components that are vented to the atmosphere, while the contaminants that do not break down are incorporated into the melt. The resulting treated material, called "Ecomelt," is then ground to a powder and blended with cement. The Ecomelt takes part in the hardening process of concrete, which is a mixture of cement, sand, gravel, and water. Further, Ecomelt reduces the quantity of other raw materials that are typically used in cement manufacturing, such as shale.

After the testing phase, which will treat 400 cubic yards of dredged material from New Jersey's upper Newark Bay, EPA and NJDOT will work with GTI to develop a commercial kiln that can treat up to 500,000 cubic yards of sediment per year.

The Cement-Lock process may also help ease tension between Long Island and Connecticut officials, who disagree about a possible long-term EPA plan to dispose of dredged materials in the Long Island Sound. Long Island residents and officials do not want potentially contaminated sediment discarded in the Sound. However, dredged material from Connecticut harbors is typically discarded there, prompting concern that its ports could become un-navigable if dredging is reduced. Using the dredged material in the Cement-Lock technology may help to provide a solution to this problem.

The research is funded by EPA, the NJDOT Office of Maritime Resources, and GTI.

2004-10155 | INT/EXT | Newsroom