Brood XIV Cicadas Emerge for First Time in 17 Years

This keystone species is loud, large, and fast — but completely harmless

June 30, 2025

enlarge

enlarge

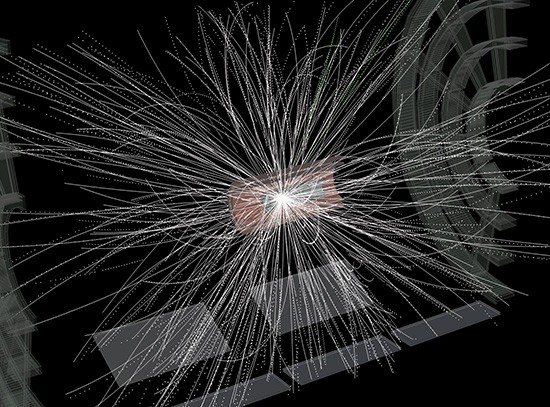

Brood XIV cicada are identifiable by their red eyes and gold wings. (Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Lab has received some noisy guests this summer — a brood of cicadas that has been incubating for the last 17 years.

This species, Brood XIV, is different from the annual cicadas that hatch in Suffolk County, identifiable by their dark bodies, gold wings, and red eyes. Their distinctive high-pitched drone has earned them the name “Pharaoh cicada,” because individual cicadas seem to buzz the syllables, “pharaoh.” But most Lab staff only hear a constant din from thousands of the critters. The insects, and their noise, could stick around until mid-July, though the population is quickly declining.

“They spend 17 years underground feeding on the tree sap from roots, and when they emerge after 17 years, you see the exoskeletons that they shed left on the trees,” explained Kathy Schwager, the natural resource manager for the Lab.

After that final molt, the insects live for a few weeks and their only goal is to reproduce, which is critically important for the ecosystem.

“They are a keystone species,” Schwager explained, noting the Lab’s location in the Long Island Central Pine Barrens, a 105,000-acre protected habitat. “They are the foundation of the ecosystem in many respects because they provide food for everything else: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and other insects.”

Brood XIV have been dive-bombing staff and crashing into windows and windshields, but Schwager says they are not harmful to people.

“They don’t bite, they don’t sting, they don’t transmit diseases. They’re just big and maybe a little eerie- looking to some people,” she said.

Brookhaven National Lab, 17 years ago

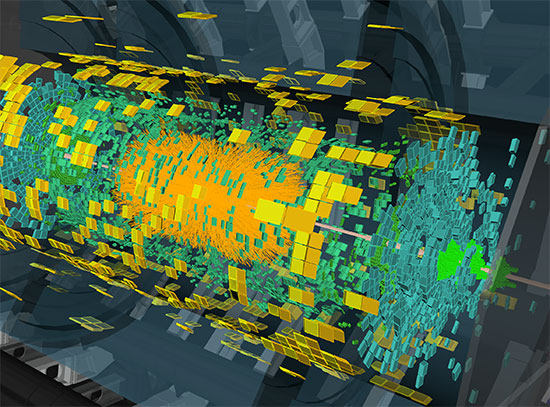

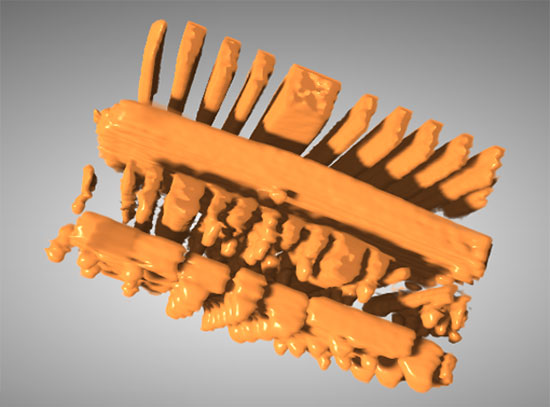

The last time Brood XIV was heard at Brookhaven Lab, in 2008, researchers were building parts for the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, which had its first collisions that year. Brookhaven Lab physicists were also making breakthroughs in high-temperature superconductors and analyzing results from recently completed collisions of deuterons with gold ions as well as polarized protons at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC). As that year’s brood laid the eggs that would become this year’s swarm, the songs of the summer were “Pocketful of Sunshine” by Natasha Bedingfield and “Disturbia” from Rihanna; the first “Iron Man” movie had just hit theaters, and the first “Hunger Games” book arrived that fall.

Since then, over the last 17 years, the U.S. has seen an overall decline in insect populations. Insects are especially vulnerable to habitat loss, as their natural areas become developed for human use.

“Cicada numbers in general have been declining so much over the years,” said Schwager. Brookhaven Lab carefully considers all new developments and rarely expands further into the woods, preserving these habitats for the next appearance of Brood XIV and the Lab’s other native wildlife.

The presence of the cicadas at Brookhaven Lab is promising. When Brood XIV comes back in 2042, they’ll get to see the next generation of cutting-edge research.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2025-22516 | INT/EXT | Newsroom