Imaging Study Reveals Effect of Smoking on Peripheral Organs

September 8, 2003

UPTON, NY - Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, who previously found reduced levels of the enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO B) in the brains of smokers, now provide compelling evidence that MAO in peripheral organs - the kidneys, heart, lungs, and spleen - is also affected by smoking. This crucial enzyme breaks down neurotransmitters and dietary amines, and too much or too little MAO B can adversely affect health and even personality.

"When we think about smoking and smoking toxicity, we usually think of the lungs," said Brookhaven chemist Joanna Fowler, one of authors of the study, which will be published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of September 8, 2003. "Here we see a very marked effect of smoking on one of the major enzymes in the body, and we see that this effect extends far beyond the lungs."

"The ground-breaking findings by Joanna Fowler's group at Brookhaven National Laboratory on the systemic effects of tobacco smoking are the result of years of investment by the Office of Science in the fundamental sciences of radiochemistry and in imaging instrumentation development," said Dr. Raymond L. Orbach, Director of the DOE's Office of Science. "With the new radiotracers we are developing, for the first time we shall be able to understand the abnormal metabolism of the brain and other organs in a wide range of disease states."

The Brookhaven team's previous research showed that the reduction of MAO B in the brains of smokers was not due to nicotine, but rather, to some other component of tobacco smoke.

"Since smoking exposes the entire body to the tobacco compounds that inhibit MAO B, we believed it had the potential to limit MAO B activity throughout the body," said Fowler, who conducted the current study to investigate this effect.

enlarge

enlarge

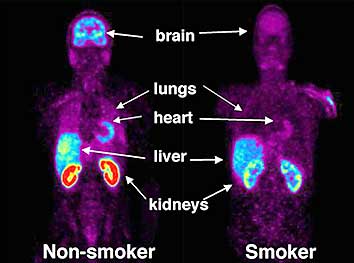

Whole body PET scans showing the distribution of radiolabeled monamine oxidase in one of the nonsmokers and one of the smokers. Red is the highest radiotracer concentration; purple is the lowest. Images are scaled so that they can be compared directly. (Click image for a 300-dpi, high-res version.)

She and her colleagues in the Medical and Chemistry Departments at Brookhaven Lab and the Psychiatry and Applied Mathematics Departments at Stony Brook University used radiotracers - radioactively "tagged" molecules designed to bind to specific biochemicals, which can then be traced using positron emission tomography (PET) scans - to determine whether smokers have reduced MAO B activity in their peripheral organs.

The scientists administered MAO B-specific binding radiotracers labeled with carbon -11 to twelve smokers and performed whole-body PET scans to measure the level of MAO B in various organs. They then compared the results with those from a group of eight nonsmokers. The study found that MAO B activity in the heart, lungs, kidneys, and spleen was significantly reduced in the smokers relative to the nonsmokers. Reductions ranged from 33 to 46 percent.

"The consequences of these reduced MAO-B levels need to be examined in greater detail," declared Fowler, "but, at the very least, it is clear that enzyme levels in smokers' peripheral organs are significantly impacted by their habit."

One of the functions performed by MAO in the body is to break down chemical compounds that elevate blood pressure, such as chemicals found in certain foods like cheese and wine, as well as some chemicals that are released by nicotine. Thus, the health consequences of reduced MAO B may be indirect and associated with other dietary substances or environmental compounds normally broken down by the enzyme.

"With the whole body exposed to the thousands of compounds in tobacco smoke, we need to be aware that these may contribute to the physiological effects of smoking," Fowler said.

This work was funded by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research within U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science; the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

2003-10207 | INT/EXT | Newsroom