Smoking Damages Key Regulatory Enzyme in the Lung

September 6, 2005

UPTON, NY - Smoking appears to reduce a key enzyme in the lungs, possibly contributing to some of smoking's deleterious health effects, according to a study published in the September issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and their collaborators. The study, which used a radiotracer to track the enzyme, also shows that smokers had a lower concentration of the tracer in the bloodstream than nonsmokers did, leading to speculation that smokers and nonsmokers may respond differently to a variety of substances administered by inhalation or intravenously, including therapeutic, anesthetic, and addictive drugs.

Researcher Joanna Fowler

"The effects of smoking on human health are enormous; yet, little is known about the pharmacologic effects of smoking on the human body apart from the effects of nicotine," noted lead author Joanna Fowler, director of the Center for Translational Neuroimaging at Brookhaven.

Fowler and collaborators from Brookhaven, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and Stony Brook University used positron emission tomography (PET) scanning and a tracer chemical that binds to a specific form of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO A) to track MAO A levels in nine smokers and nine nonsmokers. With whole-body PET imaging, researchers could measure the concentration and movement of the radiotracer and MAO A, a subtype of the enzyme crucial to mood regulation and one that breaks down chemical compounds that regulate blood pressure.

The scans revealed that MAO A was fairly well "intact" in all of the peripheral organs except in smokers' lungs, said Fowler. Smokers had MAO A levels that were 50 percent lower than in nonsmokers, she said, noting that a prior study had also shown a significant reduction of MAO A in smokers' brains.

MAO A breaks down many compounds that affect blood pressure, and the lung is a major metabolic organ in degrading some of these compounds, Fowler said. So reduced levels of MAO A in smokers' lungs may be a significant factor contributing to some of the physiological effects of smoking, including changes in blood pressure and pulmonary function.

enlarge

enlarge

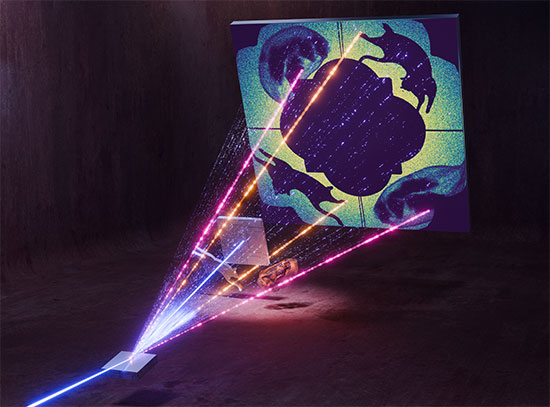

A whole-body PET scan showing the concentration of the enzyme MAO A in various body organs in a nonsmoker. Differences between smokers and nonsmokers are too small to observe visually, but mathematical analysis of the raw data clearly shows a lower concentration of MAO A in the lungs of smokers compared to nonsmokers. (Click image to download hi-res version.)

Smokers' lungs also held onto the tracer chemical much longer than nonsmokers, and the delivery of tracer into the arterial blood supply was much lower for smokers, particularly for the first few minutes after being injected, Fowler added. This finding could imply that smokers and nonsmokers respond differently to other substances that enter the body via the bloodstream, including therapeutic drugs, anesthetics, abused substances, environmental agents - even nicotine.

Fowler and her colleagues have been studying MAO for more than 30 years. Previous research by their group revealed that smokers have reductions in another subtype of the enzyme, MAO B, in the brain and in a variety of the body's peripheral organs when compared to nonsmokers (see: this release).

"These studies showing for the first time that smokers have reduced levels of MAO in their brains and in certain peripheral organs shed mechanistic light on some of the more puzzling aspects of smoking, including a reduced rate of Parkinson's disease in smokers and a high rate of smoking among people with depression and those addicted to other substances," Fowler said. The role played by MAO in other conditions associated with smoking may also be significant and deserves further investigation, considering the differences observed in the enzyme level between smokers and nonsmokers, she said.

Cigarette smoking accounts for 440,000 deaths each year in the United States, or nearly one of every five deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking kills more Americans than AIDS, illegal drugs, alcohol, car accidents, suicides and murders combined and increases one's chances of developing lung, bladder, esophageal and throat cancers; chronic lung diseases; and coronary heart and cardiovascular diseases. This research was funded by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research within the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, and by NIDA, a division of the National Institutes of Health. PET imaging is a direct outgrowth of the Department of Energy's long-standing investment in basic physics research.

"It's important that the public know about the benefits derived from the DOE's long-term investments in basic science - especially in radioisotope and radiotracer chemistry and imaging physics - which have played such an important role in introducing new nuclear medicine procedures into the practice of health care," Fowler said.

2005-10364 | INT/EXT | Newsroom