Capturing Ghosts

Quantum "ghost imaging" technique paves the way for nanoscale-resolution images at a lower X-ray dose

February 18, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

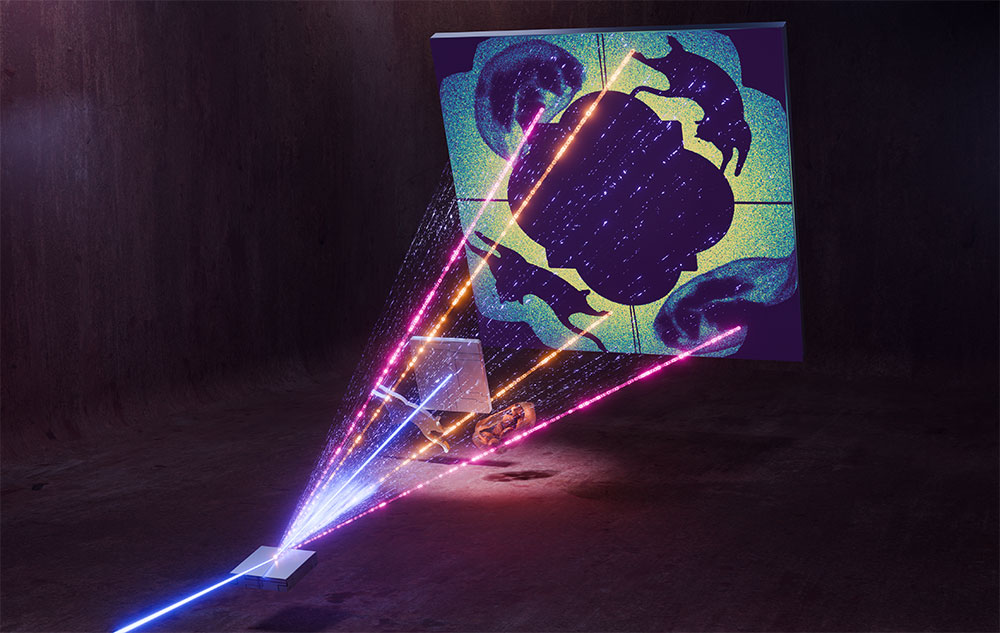

A conceptual schematic of "ghost imaging" displays the samples being imaged, which include a cat-shaped tungsten test pattern and an E. cardamomum seed. The objects are placed inside a ring on the lower two detector chips, while the upper chips are left open. By measuring paired X-ray signals at the same time, the system produces two matching images. (Valerie A. Lentz/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

UPTON, N.Y. — A group of researchers led by scientists at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, is exploring a quantum-inspired imaging approach that could set the stage for obtaining high-resolution data while reducing X-ray exposure. The method relies on pairs of quantum-entangled X-ray photons, linked particles of light from the same origin that share properties and information. In each entangled pair, one photon interacts with a sample while its partner does not. By analyzing these pairs, the team demonstrated that information carried by the untouched photon can be used to form an image, complementing information obtained from its partner. This early proof of concept could ultimately enable longer, lower-dose studies of delicate biological materials, such as plant tissues, and may one day inform lower-dose medical imaging. Their results were published in Optica.

Seeing “ghosts”

Quantum “ghost” imaging is a technique that is as intriguing as its name suggests. In conventional X-ray imaging, X-ray photons directly interact with the sample being studied. Ghost imaging, instead, uses pairs of photons that are created together and share linked properties, known as quantum correlations. One photon from each pair travels through the sample, while its partner never interacts with it at all. Despite this, the untouched photon behaves as if it has encountered the sample.

enlarge

enlarge

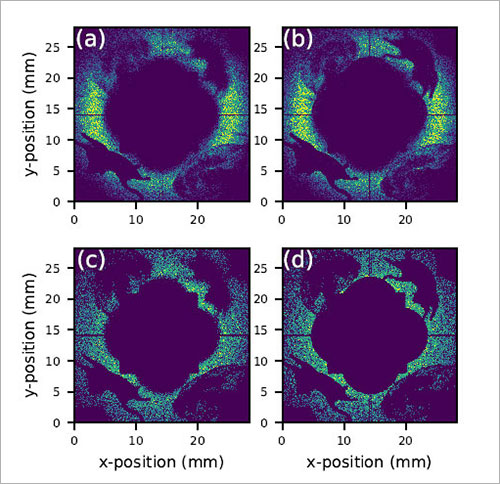

X-ray images showing how pairs of related X-ray signals line up, using both real measurements and computer models. (a) The original experimental image collected over 38 hours, before any adjustments were made. (b) The same image after researchers corrected the data to improve accuracy. (c) A computer-generated image that assumes the X-ray emission angles vary slightly around an average value. (d) A computer-generated image that assumes the X-ray emission angle stays perfectly constant. (Brookhaven National Laboratory)

“Imagine sending out pairs of sealed envelopes that contain matching codes,” explained Justin Goodrich, an assistant physicist at NSLS-II and lead author of this paper. “One envelope from each pair passes through a machine that blocks, alters, or distorts some of the codes, while its partner remains sealed and untouched. Looking at either envelope alone gives only limited insight. But when the altered envelopes are later matched with their untouched partners, the correlations between them reveal how the machine affected the codes. Quantum imaging works in much the same way: One photon probes the sample, its partner does not, and new information emerges from analyzing their correlations rather than either photon by itself.”

Taking advantage of this remarkable property, scientists can quickly reconstruct detailed information about the sample by measuring both photons to form detailed images.

Creating these correlated pairs of photons is not easy, though. The process begins by sending light through a “nonlinear” material. Unlike ordinary materials, which allow photons to reflect and refract proportionally to a light source’s intensity, nonlinear materials interact with photons in complex, disproportionate ways. This interaction can alter the photons and, under the right conditions, give rise to unusual quantum effects, like the splitting of a single photon into a correlated pair.

This process is inherently probabilistic and unpredictable, however, as not every incoming photon will divide into two linked ones. While this technique has been demonstrated many times with visible light, such as lasers, generating a substantial number of X-ray photons with the required properties is far more challenging.

“It’s very difficult to generate entangled states with X-rays,” Goodrich said. “X-rays don’t interact with matter as strongly as visible light. You can’t see through walls, but X-rays can pass right through them. Research on entanglement using lasers and visible light has been going on since the 1960s, but we’re only just beginning to catch up experimentally with X-rays. That’s what makes this work so important.”

Why X-rays?

X-rays are a powerful tool for studying nanoscale details in small biological samples, like cell organelles and plant tissues. These samples tend to be tiny and delicate, though.

“When we image tiny biological samples, the X-rays can affect the structure over time,” explained Andrei Fluerasu, lead beamline scientist at the Coherent Hard X-ray Scattering (CHX) beamline at NSLS-II. “We need to balance how much information we can get before the sample is damaged by the X-rays, which can limit how sharp or detailed our images are.”

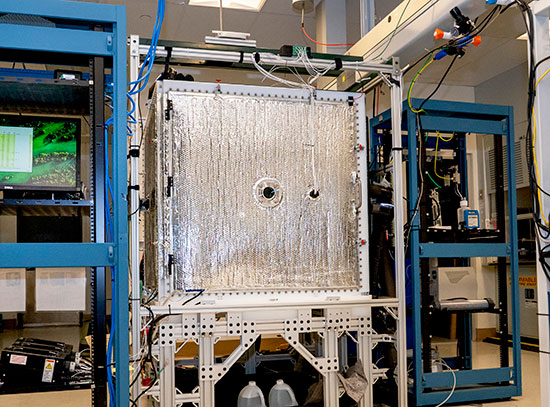

This is where correlated X-ray photons prove to be helpful. Each of the entangled photons provides valuable information to create a detailed image, including the one that doesn’t touch the sample. To test this method, the team configured the CHX beamline and employed a specialized detector setup to isolate the correlated photons. Scientists used two chips on the top of the detector to detect the “idler” photons — the ones that have not touched the sample — while the bottom two chips were positioned to pick up the “signal” photons that had interacted with the sample.

Researchers strategically placed samples in this setup, including a piece of tungsten cut into the shape of a cat, a nod to quantum mechanics pioneer Erwin Schrödinger, and a cardamom seed, serving as a small biological specimen. The team used the X-ray source at the beamline to image the sample over several hours, and they applied a formula to the resulting data to correct the blurry aberrations that can occur in images produced by the idler photons.

This approach creates what is known as a "coincidence image" that combines data from events in which both photons in a pair reach the detector. The photon on the idler side is recorded, but when scientists filter the data for these coincidences, they see the "ghost" or "twin" images appear. The presence of the idler photon is very important, as calculating the correlations or ratios of idler photons recorded to signal photons recorded enables scientists to get better statistics and information from their measurements.

The team was pleased to see that their results aligned closely with computer simulations that were performed prior to the experiment for both the original and corrected images. They also measured how closely these photon pairs are linked in space and the rate at which they are produced, recording about 7,800 photon pairs per hour.

As the experiment progressed, the researchers paid close attention to the methods and experimental conditions at the time and how they affected the quality of the image. These data will ultimately help them develop even more effective techniques in future experiments.

Collaborative efforts, comprehensive results

“Work like this required a truly multidisciplinary team,” said Sean McSweeney, director of the Biological, Environmental, Earth, and Planetary Sciences division at NSLS-II. “We brought together biologists, physicists, computational and data scientists, and synchrotron scientists. Getting this novel setup constructed and operational required the hard work and ingenuity of talented technicians and engineers at the facility. Although our focus was on biological applications, this breadth of expertise helped us optimize our experiments and gain deeper insights from the resulting data.”

Deploying advanced detectors capable of capturing individual X-ray photons while recording the precise location and arrival time of each, down to the nanosecond, drew on a wealth of internal and external expertise. Members of both NSLS-II’s Data Science and Systems Integration division and the Lab’s Computing and Data Sciences directorate were instrumental in this effort and helped the team process the massive amounts of data created by each photon event to eventually create the images.

These accomplishments represent early steps toward making the technique a practical tool for studying delicate biological materials, like cells and plant tissues, with reduced damage from intense X-ray beams. What they uncover may ultimately inform lower-dose imaging approaches in a number of fields, possibly inspiring future medical imaging approaches. Future work will focus on faster imaging, higher resolution, and the ability to study larger biological samples, including plants, seeds, and roots, to better understand living systems.

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science, the DOE Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists, the DOE Quantum Information Science Enabled Discovery program, and Brookhaven Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22772 | INT/EXT | Newsroom