Brookhaven Lab Builds Successful 'Cloud in a Box'

New convection cloud chamber produces clouds — and research possibilities

February 17, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

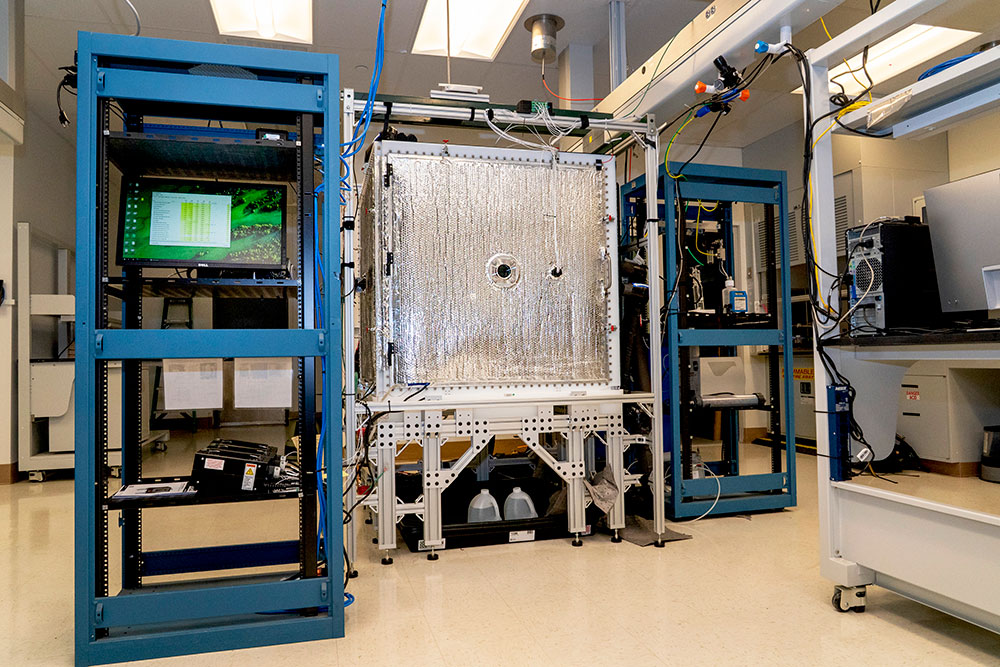

A new cloud chamber at Brookhaven National Laboratory will allow scientists to study clouds in a controlled setting. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

In a quiet laboratory, a team of atmospheric scientists and engineers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory recently gathered around a workstation to watch as little floating speckles, illuminated by a curtain of green light, swirled into a haze, then wisp of a cloud.

This instance of creation unfolded inside a programmable atmosphere they’d built from scratch.

“We saw the birth of a cloud,” said Brookhaven atmospheric scientist Arthur Sedlacek. “There was a lot of excitement and happiness, and relief, in that moment. Needless to say, we definitely weren’t quiet after that.”

Researchers will use the new convection cloud chamber, a customizable one-cubic-meter metal box, to tackle fundamental unknowns that remain about clouds.

Clouds might seem simple — white, fluffy shapes drifting overhead — but they remain one of the biggest sources of uncertainty in models of weather and Earth’s complex atmospheric system.

enlarge

enlarge

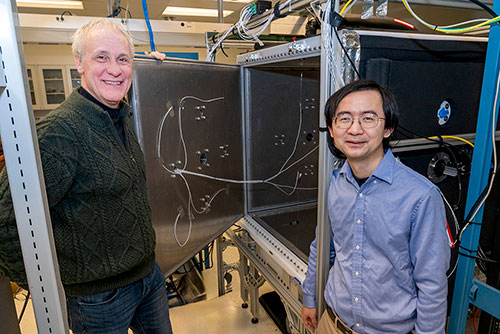

Atmospheric scientists Arthur Sedlacek (left) and Fan Yang in the cloud chamber laboratory, where they can study cloud properties under controlled conditions. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Scientists know that clouds play important roles in regulating Earth’s energy balance, controlling how water moves through the atmosphere, driving storm formation, and influencing how intense weather systems become. Still, researchers’ understanding of the physics underlying cloud processes is limited.

“We need repeatable, controlled experiments in order to tease out the key factors and mechanisms governing those underlying small-scale processes,” Sedlacek said. “For example, one long-standing unsolved problem in our community is how drizzle or raindrops are formed in warm clouds. Why do some clouds precipitate while others do not?”

Collecting key and abundant measurements from clouds in nature, while challenging, provides some data needed to address these questions. Brookhaven scientists and their collaborators have piloted specially equipped aircraft through clouds to collect such data. But each flythrough hits a cloud that has already changed since the plane’s first pass.

The cloud chamber will allow scientists to study clouds in a more controlled setting.

“The cloud chamber provides us with a unique environment to isolate and rigorously study important but still poorly understood cloud microphysical processes,” said Brookhaven atmospheric scientist Fan Yang. “We can use it to mimic real atmospheric clouds under well-controlled laboratory conditions and perform detailed, repeatable cloud measurements.”

Watch as a cloud forms in the chamber. Scientists use a green laser to see the process. (Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Controlled cloud making

Brookhaven Lab’s convection cloud chamber combines ingredients needed to make a cloud: air that is supersaturated with water and aerosol particles, tiny particles suspended in the atmosphere that can trigger the condensation of water vapor into cloud droplets.

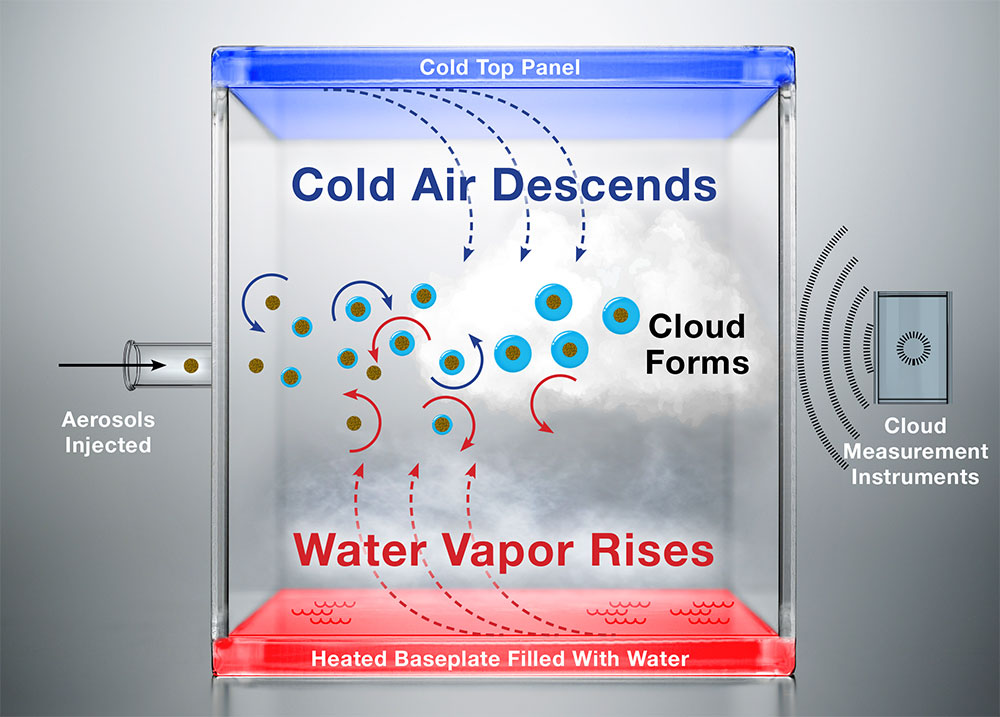

Scientists first fill the chamber’s bottom baseplate with water. Then they heat it up, releasing water vapor into the chamber through evaporation. The top panel of the box is cold. As the warm water vapor from the bottom rises and mixes with cool air from the top, it builds up an atmosphere where the air is “thick” with humidity.

“Cloud formation requires the relative humidity to be greater than 100% — a condition we refer to as supersaturation,” Sedlacek said. “Such a supersaturated environment is achieved in the chamber by the mixing of warm humid air with cold humid air.”

enlarge

enlarge

Researchers inject a mixture of table salt into the cloud chamber to provide "seeds" for cloud formation. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

To trigger cloud droplet formation in this supersaturated atmosphere, scientists inject aerosol particles, such as table salt, into the chamber to serve as “seeds” for cloud formation. When water vapor from the air condenses on the salt particles, it forms tiny cloud droplets. In the humidified environment, these droplets will continue to grow through additional condensation of water vapor. Eventually, this establishes a steady state between the cloud droplet particle size and the relative humidity.

“One major advantage of a convection cloud chamber, compared with other types of cloud chambers, is that we can maintain a turbulent cloud for hours in a steady state,” Yang said. “This will allow repeated measurements of cloud properties, which improves statistical robustness.”

The cloud chamber at Brookhaven Lab is made up of individual heating and cooling side panels that allow researchers to steer settings such as relative humidity, temperature, and the degree of mixing and swirling in the air, or turbulence, to create a complex structure. Rearranging the heating and cooling side panels will allow the creation of different internal chamber conditions, resulting in more complex cloud schemes to be formed. Additionally, the chamber is designed so that scientists can measure the influences of things like aerosol composition and size, temperature on cloud formation, cloud droplet size distribution, and cloud persistence.

“From an experimental perspective, there are lots of knobs we can turn to create specific atmospheric conditions within the chamber,” Sedlacek said. “We’ve started thinking about how we can incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning into the cloud chamber’s workflow.”

The unique modular design also offers flexibility for the future. For example, the structure is meant be expandable. Adding another cubic meter on top would expand the working volume, leading to increased cloud lifetime. This would open the door to even more ambitious studies of drizzle and rain drop formation, the researchers said.

enlarge

enlarge

This graphic illustrates how a cloud forms inside the cloud chamber as warm, moist air rises from the heated baseplate and cooler air descends from the cold top panel, driving convection. Aerosols injected into the chamber act as seeds for cloud droplets that are measured by instruments on the side of the chamber. (Joanna Pendzick/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Making measurements with advanced imaging

A crucial component of these studies is using tools that can take measurements inside the cloud chamber without touching and disrupting the cloud and its environment. The Brookhaven team is developing next-generation instrumentation and methods to make this possible.

“We want to be able detect the transition of aerosols to cloud droplets to drizzle without sticking instruments inside the chamber so that we don’t disrupt the air flow,” Sedlacek said. “To realize this goal, we’ll use light.”

Scientists aim to, first, detect aerosols particles that activate into cloud droplets by tagging the particles with fluorescent dye. Tagged and activated aerosols will light up when hit by a laser. Next, researchers will use time-correlated photon-counting lidar — a laser-based remote-sensing instrument — to observe a cloud’s structure at the scale of a single centimeter. Then, to detect drizzle and follow its movement within the cloud chamber, they plan to use novel THz radar that captures individual droplets and measures how fast they fall.

Powered by collaboration

What started out as brainstorming, scribbles, and long chats turned into a solid design for a successful convection cloud chamber — one of only two in the nation — thanks to close collaboration between scientists, engineers, and support staff across Brookhaven Lab.

“The expertise necessary to create something like this chamber requires modelers, observationalists, experimentalists, and engineers to pull it all together — and that is part and parcel of what national labs do,” Sedlacek said.

Engineers from the Lab’s Instrumentation Department and scientists from the Environmental Science and Technology Department began collaborating on the cloud chamber a few years ago, after a meeting that highlighted Instrumentation’s capabilities and how they could support scientific research. That discussion sparked the idea to build a cloud chamber together.

enlarge

enlarge

The cloud chamber design and build process was a team effort that included scientists, technicians, engineers, business support, and administrative staff. A portion of the team, from left to right: Cole Trapani, Ruba Akram, Steven Andrade Scott Smith, Donna Jean Chiossone, Connie-Rose Deane, Andrew McMahon, Fan Yang, Arthur Sedlacek, Sean Robinson, Nathaniel Speece-Moyer. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

As the team formed, engineers refined the design while learning more about the scientific requirements — especially the need for precise temperature control.

“It was a very iterative process,” said mechanical engineer Nathaniel Speece-Moyer. “We have great people and resources on site, and we used our engineering judgment to weigh different design options with frequent input from the scientific staff. We converged on a final design that the group is happy with.”

The final design is modular and carefully controls temperature while ensuring that air and particles inside the chamber remain undisturbed. All of the hardware is located outside the chamber to avoid interfering with experiments.

Many of the components were fabricated in house by Brookhaven Lab’s fabrication services, which reduced costs and allowed the engineering team to make adjustments along the way, said mechanical engineer Connie-Rose Deane.

“This cloud chamber is a great example of how engineers, scientists, and technicians can collaborate together to achieve something special,” Deane said. “We also had a lot of support from budget, safety, and facilities staff. What really powered me through this work was the excitement everyone brought to the project.”

Throughout the process, the team also drew on experience gained from the Michigan Technological University’s (MTU) Pi Cloud Chamber, the only other convection cloud chamber in the United States. Raymond Shaw, a professor at MTU, has a joint appointment with Brookhaven’s Environmental Science and Technology Department and was key to developing both chambers.

“Cloud chamber science is experiencing a resurgence for several reasons,” Shaw said. “Perhaps most importantly, the atmospheric physics community has realized that there are still fundamental questions about how aerosol and cloud particles interact that directly influence how we can simulate atmospheric flows using coarse-resolution models, such as for storm or weather forecasting. The simplified, controlled, repeatable, and well-characterized conditions provided by a laboratory experiment in a cloud chamber can provide important insights.”

At the same time, additional advances now make it possible to simulate these processes in great detail, enabling direct comparisons between experiments and computational models, Shaw said.

Yang added: “The cloud chamber at Brookhaven Lab is the outcome of more than 10 years of experience. We’ve learned a lot from the Michigan Tech Pi Cloud Chamber group and from a multi-institution research activity jointly funded by DOE and the National Science Foundation aimed at exploring ideas for a larger-scale cloud chamber facility. We want to shout out all the work that led to this very smart design.”

Scientists, engineers, and technicians worked together to assemble Brookhaven Laboratory's convection cloud chamber. (Timothy Kuhn/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Looking beyond the clouds

The potential of Brookhaven Lab’s new “cloud in a box” testbed stretches beyond just studying clouds. Its creators encourage suggestions for other research areas it can support.

Ideas floated for potential uses so far include investigations into how atmospheric conditions impact the performance of energy and information infrastructure, as well as the movement of bioaerosols — tiny natural particles such as pollen and pathogens.

“The environment we create inside this chamber opens up other applications,” Sedlacek said. “We welcome the opportunity for ‘out-of-the-box' ideas that this brand-new capability at Brookhaven Lab can provide.”

This work was supported by Brookhaven’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22711 | INT/EXT | Newsroom