Harvard Physicist Peter Galison to Speak at Brookhaven Lab on the History of Physics, November 2 and 3

September 28, 2006

UPTON, NY - Peter Galison, Pellegrino Professor of the History of Science and Physics at Harvard University, will give a series of three lectures at the Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, all in Berkner Hall. On Thursday, November 2, at 4 p.m., he will discuss "Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps," and on Friday, November 3, he will give two lectures: one at 11 a.m. about the restructuring of modern physics, titled "The Pyramid and the Ring," and another at 4 p.m. - a brief history of scientific objectivity from the 19th century to the present, titled "Picturing Objectivity."

Sponsored by Brookhaven Science Associates through the George B. Pegram Lectureship Series in which distinguished scholars examine topics of both scientific and general interest, the free lectures are open to the public. Visitors age 16 and over must bring a photo ID.

In the November 2 lecture at 4 p.m., Galison will discuss how the world-famous physicist Albert Einstein and Henri Poincaré, a well-known nineteenth-century mathematician and theoretical physicist, were able to develop the insights that led to their groundbreaking discoveries in special relativity, which describes the motion of particles at close to the speed of light. Galison asserts that they were both immersed in practical jobs that brought them in close contact with new developments in science and technology. Einstein's job in a patent office located him squarely in the middle of a wealth of technological developments and patents related to the coordination of clocks. Working at the Paris Bureau of Longitude, Poncaré was involved with the use of precision-coordinated clocks for long-distance longitude determination.

The second lecture, on November 3 at 11 a.m., will focus on the restructuring of physics in modern times. Galison maintains that certain branches of research that are generally thought to be physics are not considered part of the discipline by some scientists. For example, string theory is accused of being too far from experiment and closer to mathematics or philosophy than physics, and nanoscience is accused of being too close to engineering and not basic enough to be physics. Galison believes that the discipline of physics is changing, moving from a pyramid-like structure with fundamental physics at the top, to something more like a ring, with connected parts but no universally accepted center.

In his final talk, at 4 p.m. on November 3, Galison will discuss the history of scientific objectivity, from the early 19th century to the present. In the early 1800s, scientific objectivity became a goal. Between 1830 and 1930, scientific atlases helped define "mechanical objectivity" at the time - performing science according to a certain set of procedures without variation. But the fate of scientific objectivity kept changing. Twentieth-century scientists questioned mechanical objectivity and demanded more individual input and interpretation of results. With that shift came a new view of the "right" scientific self, one now explicitly making use of intuition, expertise, and the unconscious.

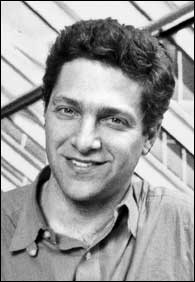

Peter Louis Galison received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in both physics and the history of science, in 1983. Before he joined the Harvard faculty in 1992, Galison was Professor of History, Philosophy, and Physics at Stanford University. In 1997, he was named a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellow, and, in 1999, he won the Max Planck Research Award.

Galison's work focuses on the exploration of twentieth century physics, and, in particular, he explores how experimenters, instrument makers and theorists are interconnected. Among his numerous publications are: How Experiments End (Chicago University Press, 1987), Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics (Chicago University Press, 1997), and Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps (WW Norton & Co, Inc. 2003).

2006-10540 | INT/EXT | Newsroom