Epilepsy Drug Stops Nicotine's Effects in Animals

Same Drug Already Shows Promise in Animals For Treating Cocaine Addiction

December 2, 1998

Washington, DC — Smokers who want to kick the habit may find powerful help from a European epilepsy drug that already has shown promise in treating cocaine's effects in animals, U.S. Secretary of Energy Bill Richardson announced today.

That is the conclusion of animal studies published today in the journal Synapse by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), St. John's University, New York University School of Medicine and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

"Smoking-related diseases are responsible for 1 in 5 deaths in the U.S.," said Energy Secretary Bill Richardson at a press conference. "With 35 million smokers trying to quit each year, and only 7 percent succeeding for more than a year, this new effort, if successful, could save millions of lives. Once again, government-funded scientists are at the forefront of the cutting- edge research enabling us to confront a major health problem."

The same team published results in August showing that the epilepsy drug — known as gamma vinyl-GABA, or GVG — looks very promising as a treatment for cocaine addiction. In animals, it prevented the dramatic changes in brain chemistry and behavior brought on by cocaine.

The new paper shows that GVG does the same for nicotine. And, the dose needed to block nicotine was about one-tenth of that used to block cocaine's effects in animals. The nicotine-blocking dose corresponds to about one-tenth to one-twentieth the dose currently used to treat epilepsy in humans. Upcoming clinical trials will determine the dosage needed in humans.

According to Dr. Alan I. Leshner, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, "This study confirms the importance of the brain's GABA system as an important target for potential anti-addiction medications, like GVG. It also emphasizes that there likely are common brain mechanisms underlying addiction to all drugs and gives hope that we can develop a single medicine to use in treating addiction, whatever the primary addictive drug."

The evidence is so strong that the scientists think GVG might work better and have fewer side effects than other stop-smoking treatments available today. It is not addictive, is not based on nicotine and has been used safely in Europe by epileptic children for more than a decade.

"Of all the addictive drugs that exist, nicotine is the most frequently abused drug in the world, and every smoker who's tried knows how hard it is to quit," said Stephen Dewey, the lead author on the paper. "We've shown in animals that the proper dose of GVG can stop nicotine's addictive effects entirely."

The team's research also suggests that GVG may work against a variety of other addictions.

"We're gaining confidence that this approach could offer hope to all addicts, from smokers and alcoholics to hard-core heroin and cocaine users," said team member Charles Ashby of St. John's.

Added co-author Jonathan Brodie of New York University, "Since the same brain chemistry changes may be common to all these addictions, it follows that a single well-aimed strategy, combined with a person's desire to quit, could assist in defeating them all."

In order to show whether GVG could be as effective in humans as it was in animals, clinical trials are now being planned at institutions in Europe, Canada and the United States.

Though GVG is not currently approved in the U.S. to treat epilepsy, U.S. institutions can apply to conduct clinical trials under "investigative new drug" protocols from the federal Food & Drug Administration.

The research grew out of pioneering cooperative work to understand the brain's chemical messengers, called neurotransmitters, and the effect of addictive drugs on the balance of those chemicals in the brain. One neurotransmitter in particular, called dopamine, plays a central role in the sensations and behaviors associated with all drug use.

The GVG results on cocaine were published after more than a decade of investigation that started when Dewey and Jonathan Brodie of New York University looked at the way brain cells talk to one another, especially in people with schizophrenia. Soon after receiving encouraging results on cocaine, the team began testing GVG against other addictive substances. Work on alcohol, heroin, morphine, amphetamines and methamphetamines is nearing completion.

Fighting Tobacco's Addictive Hook

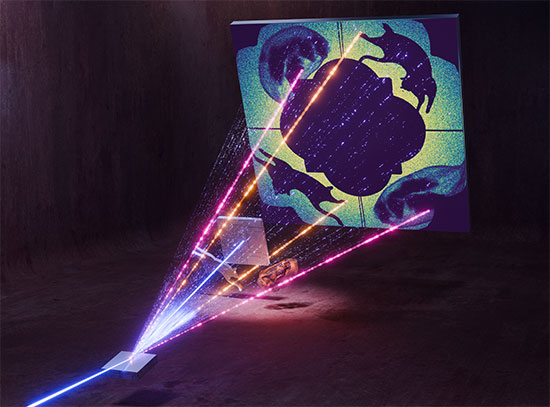

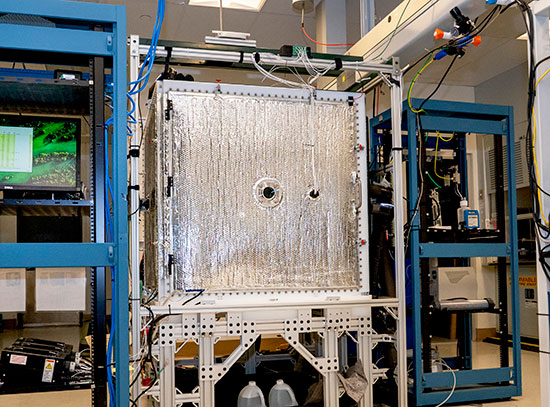

The researchers looked carefully at how different doses of GVG changed nicotine's ability to alter brain dopamine levels in rodents and primates. They used sophisticated imaging techniques to measure dopamine concentrations in the brains of both nicotine-addicted rodents and those that had never been exposed to nicotine. And they performed brain scans on female baboons given intravenous nicotine.

"Nicotine doubles the brain's dopamine level, sending a rush of pleasure and a signal that you should smoke over and over again," said Dewey. "But an appropriate dose of GVG taken before nicotine exposure can completely block nicotine's effects on brain dopamine."

GVG increases the levels of another brain chemical, GABA, which decreases dopamine production. So, GVG prevents nicotine from causing dramatic changes.

Studying the Behavioral Effects

As any smoker will attest, nicotine addiction is not just a matter of the mild rush caused by smoking. The mere sight or smell of cigarettes, or of a smokers' hangout, can bring on a craving.

This kind of behavioral effect is what makes quitting smoking so hard. So, Ashby and his colleagues tested GVG's effect on rats' tendency to seek out a place where they had previously received nicotine, and their ability to acquire that tendency in the first place. The technique is called conditioned-place preference, or CPP.

"It was astounding," said Ashby. "Not only could GVG keep addicted animals from returning to the nicotine-associated place — a somewhat higher dose kept non-addicted ones from getting the habit in the first place." He noted that similar tests have not been done on stop-smoking therapies currently on the market.

The research was funded by the Energy Department, the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Mental Health. In addition to Dewey, Ashby and Brodie, the paper's authors are Bryan Horan of St. John's, Madina Gerasimov of BNL and Eliot Gardner of Einstein.

1998-10857 | INT/EXT | Newsroom