Beetlejuice! Secrets of beetle sprays unlocked at the Advanced Photon Source

May 5, 2015

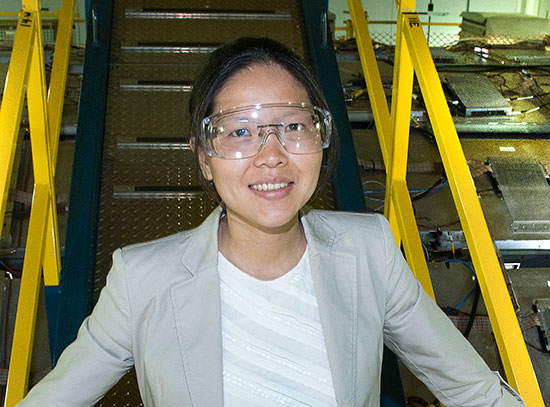

The following news release was issued by Argonne National Laboratory on April 30, 2015. Wah-Keat Lee, a beamline scientist at Brookhaven National Laboratory, is a co-author on the corresponding paper published in Science, which describes a study of the defense mechanism used by bombardier beetles, which eject rapid pulses of a hot, noxious spray from their abdomens via a succession of internal chemical reactions and explosions. Lee, who is developing the Full-Field X-Ray Imaging beamline at Brookhaven's new synchrotron, founded a program at Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) to use x-ray imaging to study insect behavior and anatomy. In this work, he assisted a team of biologists with the x-ray study, including guiding specimen preparation, experimental setup, and image processing. At NSLS-II, Brookhaven's newest synchrotron and the world leader in x-ray brightness and flux, the Full-Field X-ray Imaging beamline will be able to accommodate complementary studies into insect anatomy using preserved specimens.

We humans forbade it a long time ago, but there's one insect that uses chemical warfare of the sort we banned in the Geneva Conventions. That's the bombardier beetle, which creates a noxious, boiling hot stream of chemicals inside its body to spray at enemies when threatened.

Researchers using the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, have gotten the first-ever look inside the living beetle as it sprays. The results are published today in Science.

Scientists and engineers have long been interested in the beetles' rapid-pulse firing—more than 600 times per second—with the intent of stealing the technology: it's been studied for everything from ways to design jet engines that re-start in midair to a deterrent to ATM vandals.

"You could take high-speed photographs of the outside as the spray came out, and you could dissect it to look at the anatomy," said Brookhaven National Laboratory physicist and former Argonne scientist Wah-Keat Lee, who co-authored the study, "but you really couldn't see inside a living insect until we were able to do this study at the APS."

"We were not only able to see how the gas and vapor react inside the beetle, but also quantify the reactions that happen," he said.

The beetles store the chemicals in two separate compartments inside their bodies: a reservoir holding most of the chemicals and an armored chamber that contains enzymes to jump-start the reaction. When they're ready to fire, a valve between the two compartments opens and the chemicals react to form a boiling, high-pressure cloud that is ejected with a bang.

"What's interesting," Lee said, "is that it appears the reaction creates such high pressure that it pushes the valve closed automatically, which readies it for the next pulse. This means the beetle doesn't need a high-speed muscle to repeatedly open and close the valve, and only has to expend energy to open it." At 600 times per second, that's a lot of energy saved.

This new understanding of how the glands produce—and survive—repetitive explosions could provide new design principles for technologies relating to blast mitigation and propulsion, the authors said.

The GIF below shows the reaction, which takes place over 28 milliseconds in real time—slowed down so you can follow the action at 25 frames per second. (Researchers at the APS took video at 2,000 frames per second.)

"The APS is a powerful tool that allowed an entire new line of investigation into living insects," Lee said. "There's much more that's waiting to be studied."

The paper, "Mechanistic Origins of Bombardier Beetle (Brachinini) Explosion-Induced Defensive Spray Pulsation," was published in Science on May 1.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office through the MIT Institute of Soldier Nanotechnologies; by the National Science Foundation; by the U.S. Department of Defense; and by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The Advanced Photon Source is supported by the Department of Energy's Office of Science.

Other study authors were MIT's Christine Ortiz and Eric Arndt and the University of Arizona's Wendy Moore.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

2015-11719 | INT/EXT | Newsroom