Tiny Particles that Seed Clouds Can Form from Trace Gases Over Open Sea

Understanding previously undocumented source of new particle formation will improve models of aerosols, clouds, and their impact on Earth's climate

January 22, 2021

enlarge

enlarge

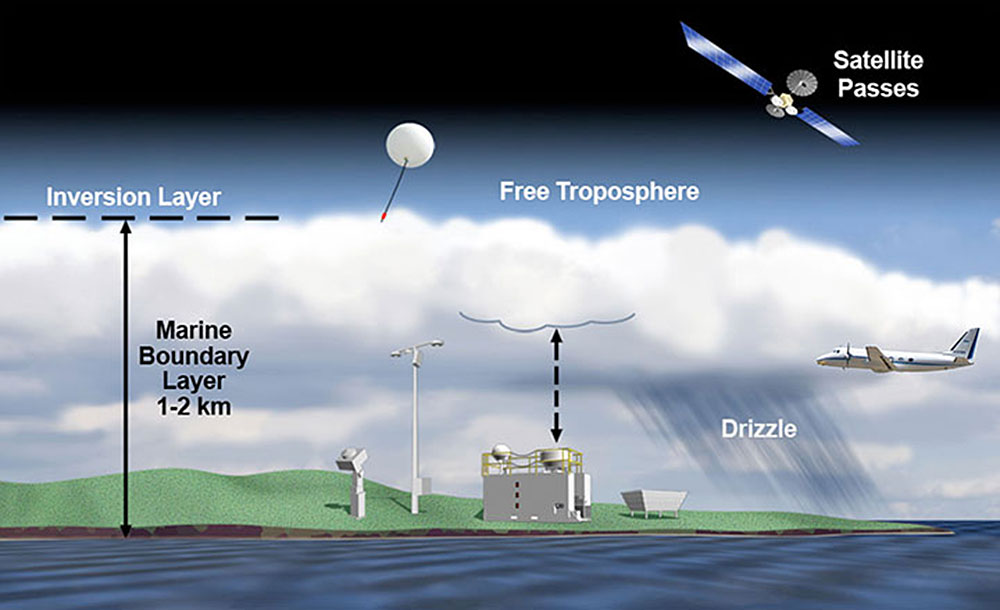

Results from a study of clouds and aerosols conducted in the Azores revealed that new particles can seed the formation of clouds in the marine boundary layer—the atmosphere up to about a kilometer above Earth's surface—even over the open ocean, where the concentration of precursor gases was expected to be low. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

UPTON, NY – New results from an atmospheric study over the Eastern North Atlantic reveal that tiny aerosol particles that seed the formation of clouds can form out of next to nothingness over the open ocean. This “new particle formation” occurs when sunlight reacts with molecules of trace gases in the marine boundary layer, the atmosphere within about the first kilometer above Earth’s surface. The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, will improve how aerosols and clouds are represented in models that describe Earth’s climate so scientists can understand how the particles—and the processes that control them—might have affected the planet’s past and present, and make better predictions about the future.

“When we say ‘new particle formation,’ we’re talking about individual gas molecules, sometimes just a few atoms in size, reacting with sunlight,” said study co-author Chongai Kuang, a member of the Environmental and Climate Sciences Department at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory. “It’s interesting to think about how something of that scale can have such an impact on our climate—on how much energy gets reflected or trapped in our atmosphere,” he said.

enlarge

enlarge

Using an aircraft outfitted with 55 atmospheric instrument systems, scientists traversed horizontal tracks above and through clouds and spiraled down through atmospheric layers to provide detailed measurements of aerosols and cloud properties. The aircraft data were supplemented by measurements made by ground-based radars and other instruments. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

But modeling the details of how aerosol particles form and grow, and how water molecules condense on them to become cloud droplets and clouds, while taking into consideration how different aerosol properties (e.g., their size, number, and spatial distribution) affect those processes is extremely complex—especially if you don’t know where all the aerosols are coming from. So a team of scientists from Brookhaven and collaborators in atmospheric research around the world set out to collect data in a relatively pristine ocean environment. In that setting, they expected the concentration of trace gases to be low and the formation of clouds to be particularly sensitive to aerosol properties—an ideal “laboratory” for disentangling the complex interactions.

“This was an experiment that really leveraged broad and collaborative expertise at Brookhaven in aerosol observations and cloud observations,” Kuang said. Three of the lead researchers—lead authors Guangjie Zheng and Yang Wang, and Jian Wang, principal investigator of the Aerosol and Cloud Experiments in the Eastern North Atlantic (ACE-ENA) campaign—began their involvement with the project while working at Brookhaven and have remained close collaborators with the Lab since moving to Washington University in St. Louis in 2018.

Land and sea

enlarge

enlarge

Brookhaven Lab atmospheric scientist Chongai Kuang (center) with Art Sedlacek (left) and Stephen Springston (right) aboard ARM's Gulfstream-159 (G-1) aircraft during a 2010 atmospheric sampling mission that was not part of this study. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

The study made use of a long-term ground-based sampling station on Graciosa Island in the Azores (an archipelago 850 miles west of continental Portugal) and a Gulfstream-1 aircraft outfitted with 55 atmospheric instrument systems to take measurements at different altitudes over the island and out at sea. Both the ground station and aircraft belong to the DOE Office of Science’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility, managed and operated by a consortium of nine DOE national laboratories.

The team flew the aircraft on “porpoise flights,” ascending and descending through the boundary layer to get vertical profiles of the particles and precursor gas molecules present at different altitudes. And they coordinated these flights with measurements taken from the ground station.

The scientists hadn’t expected new particle formation to be happening in the boundary layer in this environment because they expected the concentration of the critical precursor trace gases would be too low.

“But there were particles that we measured at the surface that were larger than newly formed particles, and we just didn’t know where they came from,” Kuang said.

The aircraft measurements gave them their answer.

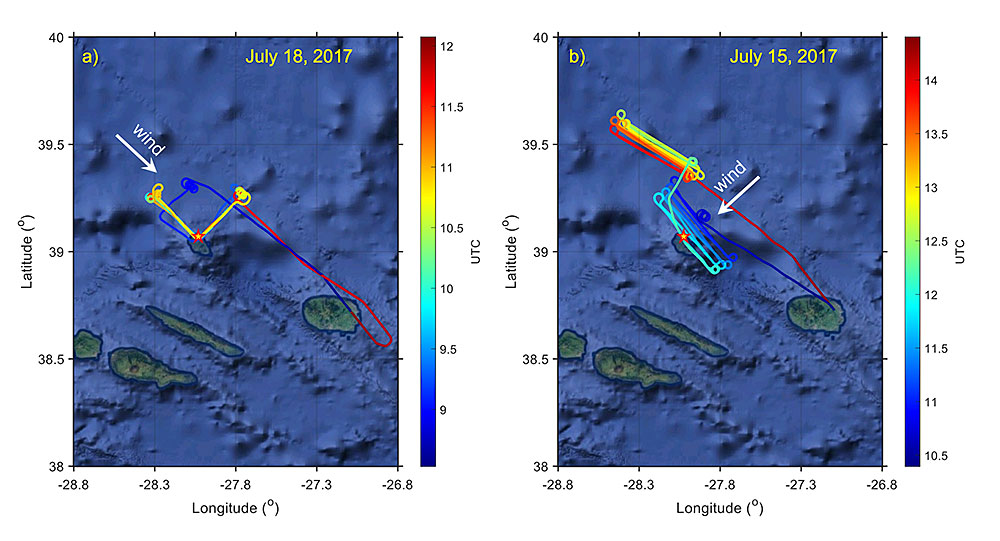

enlarge

enlarge

Many of the choreographed flight paths for this study traversed the open ocean and also crossed within the ranges of the ground-based scanning radars at DOE's Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Climate Research Facility on Graciosa Island in the Azores. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

“This aircraft had very specific flight patterns during the measurement campaign,” Kuang said. “They saw evidence that new particle formation was happening aloft—not at the surface but in the upper boundary layer.” The evidence included a combination of elevated concentrations of small particles, low concentrations of pre-existing aerosol surface area, and clear signs that reactive trace gases such as dimethyl sulfide were being transported vertically—along with atmospheric conditions favorable for those gases to react with sunlight.

“Then, once these aerosol particles form, they attract additional gas molecules, which condense and cause the particles to grow to around 80-90 nanometers in diameter. These larger particles then get transported downward—and that’s what we’re measuring at the surface,” Kuang said.

“The surface measurements plus the aircraft measurements give us a really good spatial sense of the aerosol processes that are happening,” he noted.

At a certain size, the particles grow large enough to attract water vapor, which condenses to form cloud droplets, and eventually clouds.

Both the individual aerosol particles suspended in the atmosphere and the clouds they ultimately form can reflect and/or absorb sunlight and affect Earth’s temperature, Kuang explained.

Study implications

enlarge

enlarge

Framed by a brilliant rainbow, ARM's Gulfstream-159 (G-1) research aircraft sits on the tarmac on Terceira Island during the Aerosol and Cloud Experiments in the Eastern North Atlantic (ACE-ENA) winter 2018 intensive operation period in the Azores. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

So now that the scientists know new aerosol particles are forming over the open ocean, what can they do with that information?

“We’ll take this knowledge of what is happening and make sure this process is captured in simulations of Earth’s climate system,” Kuang said.

Another important question: “If this is such a clean environment, then where are all these precursor gases coming from?” Kuang asked. “There are some important precursor gases generated by biological activity in the ocean (e.g., dimethyl sulfide) that may also lead to new particle formation. That can be a nice follow-on study to this one—exploring those sources.”

Understanding the fate of biogenic gases such as dimethyl sulfide, which is a very important source of sulfur in the atmosphere, is key to improving scientists’ ability to predict how changes in ocean productivity will affect aerosol formation and, by extension, climate.

The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science, DOE’s Atmospheric System Research, and by NASA. In addition to the researchers from Brookhaven Lab and Washington University, the collaboration included scientists from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory; Missouri University of Science and Technology; the University of Washington, Seattle; NASA Langley Research Center; Science Systems and Applications Inc. in Hampton, Virginia; the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany; and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2021-17638 | INT/EXT | Newsroom