LZ Sets a World's Best in the Hunt for Galactic Dark Matter and Gets a New Look at Neutrinos from the Sun's Core

The LUX-ZEPLIN experiment analyzed the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector

December 8, 2025

By Lauren Biron, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

enlarge

enlarge

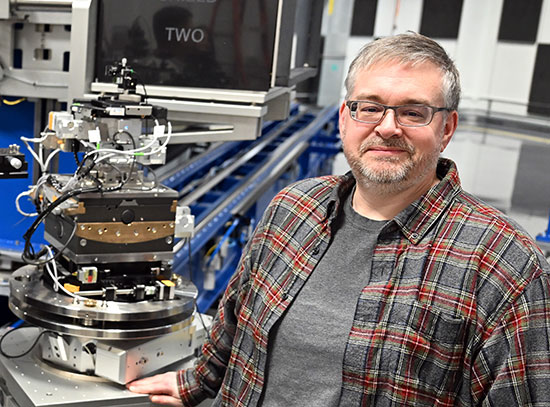

Photomultiplier tubes inside the LZ detector are designed to capture faint flashes of UV light that could signal a dark matter interaction. Credit: Matthew Kapust/Sanford Underground Research Facility

Editor's note: The following news release was origninally issued by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on behalf of the LZ collaboration, a group of scientists conducting an underground experiment designed to directly detect theorized dark matter particles known as WIMPs (weakly interacting massive particles). Scientists from DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory neutrino and nuclear chemistry group (NNC) developed the liquid scintillator that fills an essential component of the detector designed to veto false signals. The group produced 20 tons of gadolinium-doped liquid scintillator and delivered the materials to the LZ detector at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in Lead, South Dakota in 2020. For more information about Brookhaven’s role in this research, contact Karen McNulty Walsh, 631-344-8350, kmcnulty@bnl.gov.

There’s more to the universe than meets the eye. Dark matter, the invisible substance that accounts for 85 percent of the mass in the universe, is hiding all around us – and figuring out exactly what it is remains one of the biggest questions about how our world works. The newest results from LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) extend the experiment’s search for low-mass dark matter and set world-leading limits on one of the prime dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs. They also mark the first time LZ has picked up signals from neutrinos from the sun, a milestone in sensitivity.

LZ is an international collaboration of 250 scientists and engineers from 37 institutions. The detector is managed by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and operates nearly one mile below ground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in South Dakota.

enlarge

enlarge

The LUX-ZEPLIN main detector in a surface lab before installation underground. Credit: Matthew Kapust/Sanford Underground Research Facility

The new results use the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector and have unmatched sensitivity. The analysis, based on 417 live days of data that were taken from March 2023 to April 2025, found no sign of WIMPs with a mass between 3 GeV/c2 (gigaelectronvolts/c2), roughly the mass of three protons, and 9 GeV/c2. It’s the first time LZ researchers have looked for WIMPs below 9 GeV/c2, and the world-leading results above 5 GeV/c2 further narrow down possibilities of what dark matter might be and how it might interact with ordinary matter. The results were presented today in a scientific talk at SURF and will be released on the online repository arXiv. The paper will also be submitted to the journal Physical Review Letters.

“We have been able to further increase the incredible sensitivity of the LUX-ZEPLIN detector with this new run and extended analysis,” said Rick Gaitskell, a professor at Brown University and the spokesperson for LZ. “While we don’t see any direct evidence of dark matter events at this time, our detector continues to perform well, and we will continue to push its sensitivity to explore new models of dark matter. As with so much of science, it can take many deliberate steps before you reach a discovery, and it’s remarkable to realize how far we’ve come. Our latest detector is over 3 million times more sensitive than the ones I used when I started working in this field.”

Dark matter has never been directly detected, but its gravitational influence shapes how galaxies form and stay together; without it, the universe as we know it wouldn’t exist. Because dark matter doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light, researchers have to find a different way to “see” it.

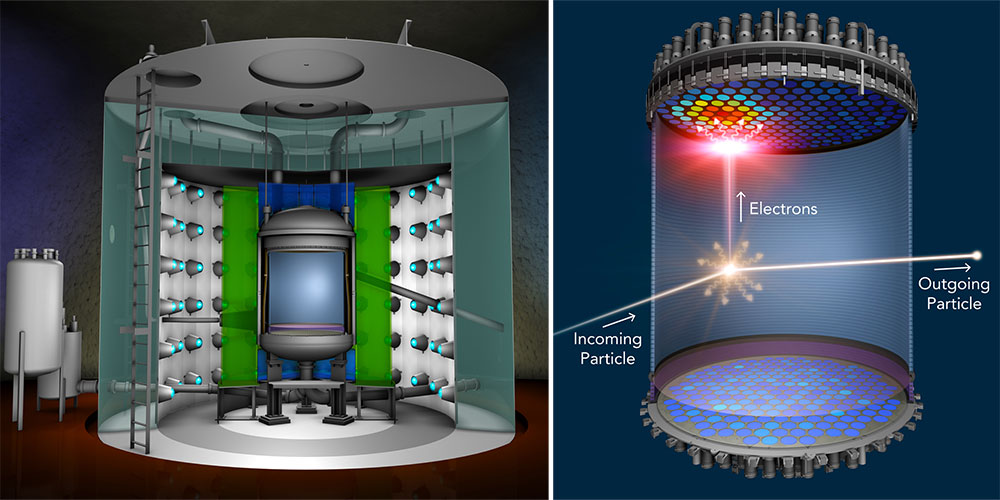

LZ uses 10 tonnes of ultrapure, ultracold liquid xenon. If a WIMP hits a xenon nucleus, it deposits energy, causing the xenon to recoil and emit light and electrons that the sensors record. Deep underground, the detector is shielded from cosmic rays and built from low-radioactivity materials, with multiple layers to block (or account for) other particle interactions – letting the rare dark matter interactions stand out.

“When I step back and consider what we’ve achieved – a world-leading search for these low-mass WIMPs using the faintest signals we can see with our detector – it’s extremely rewarding, and the perfect demonstration of the experiment working as it should,” said David Woodward, a scientist at Berkeley Lab and deputy operations manager for LZ. “The result is possible because of diligent work to keep the experiment operating and collecting high-quality data over several years. It’s a team effort, with each individual bringing their care and expertise.”

LZ’s extreme sensitivity, designed to hunt dark matter, now also allows it to detect neutrinos – fundamental, nearly massless particles that are notoriously hard to catch – in a new way. (Fittingly, LZ sits in the same underground cavern where Ray Davis ran his decades-long, Nobel Prize-winning experiment on neutrinos).

enlarge

enlarge

LZ uses a cylindrical chamber full of liquid xenon to look for dark matter. It is surrounded by additional layers to detect or block background particles (left). When a WIMP or neutrino collides with a xenon atom (right), the xenon atom emits a flash of light and electrons. The light is detected at the top and bottom of the liquid xenon chamber. An electric field pushes the electrons to the top of the chamber, where they generate a second flash of light. Valid WIMP or neutrino interactions cause no signal in the additional layers. Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

The analysis showed a new look at neutrinos from a particular source: the boron-8 solar neutrino produced by fusion in our sun’s core. This data is a window into how neutrinos interact and the nuclear reactions in stars that produce them. But the signal also mimics what researchers expect to see from dark matter. That background noise, sometimes called the “neutrino fog,” could start to compete with dark matter interactions as researchers look for lower-mass particles.

“To maximize our dark matter sensitivity, we had to reduce and carefully model our instrumental backgrounds, and worked hard in calibrating our detector to understand what types of signals solar neutrinos would produce,” said Ann Wang, associate staff scientist at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and co-lead of the analysis. “With this dataset, we have officially entered the neutrino fog, but only when searching for dark matter with these smaller masses. If dark matter is heavier – say, 100 times the mass of a proton – we’re still far away from neutrinos being a significant background, and our discovery power there is unaffected.”

The boron-8 solar neutrinos interact in the detector through a process that was only observed for the first time in 2017: coherent elastic neutrino-nucleus scattering, or CEvNS. In this process, a neutrino interacts with an atomic nucleus as a whole, rather than just one of the particles inside it (a proton or neutron). Hints of boron-8 solar neutrinos interacting with xenon appeared in two detectors last year: PandaX-4T and XENONnT. Those experiments were shy of the standard threshold for a physics discovery, a confidence level known as “5 sigma,” reporting 2.64 and 2.73 sigma (respectively). The new LZ result improves the significance to 4.5 sigma, passing the 3-sigma threshold that is considered “evidence.”

“Seeing these neutrino interactions is a pivotal milestone,” said Dan Kodroff, a Chamberlain Fellow at Berkeley Lab and co-lead of the analysis. “It simultaneously showcases LZ's ability to detect signals of cosmic origin while also giving us new avenues for probing solar and neutrino physics to test the Standard Model.”

While the background signal from neutrinos presents challenges for the dark matter detector at low masses (3-9 GeV/c2), its new secondary role as a solar neutrino observatory gives theorists more information for their models of neutrinos, which still hold many mysteries themselves. LZ can provide an independent measurement of how many boron-8 neutrinos are coming from the sun (known as “neutrino flux”), detect future neutrino bursts to better understand supernovae, and help study one of the fundamental parameters that describe how particles interact (the weak mixing angle).

Reaching into the neutrino fog also highlights LZ’s performance, with the ability to sense incredibly tiny amounts of energy from individual particle interactions.

enlarge

enlarge

LZ's central detector was assembled in a surface cleanroom and moved to the nearly mile-deep campus at the Sanford Underground Research Facility. The underground location shields the experiment from cosmic rays. Credit: Matthew Kapust/Sanford Underground Research Facility

“This result is clear confirmation that LZ could observe even low-mass dark matter,” said Scott Kravitz, assistant professor at The University of Texas at Austin and the analysis coordinator for LZ. “It’s particularly powerful to look at something fully out of our control – nuclear fusion from the sun – and find that the predicted rate of events from that process is consistent with our observations. It means the detector and our experiment are as sensitive as expected, and capable of finding dark matter if it’s within the range where we’re searching.”

LZ is scheduled to collect over 1,000 days of live search data by 2028, more than doubling its current exposure. With that enormous and high-quality dataset, LZ will become more sensitive to dark matter at higher masses in the 100 GeV/c2 to 100 TeV/c2 (teraelectronvolt) range. Collaborators will also work to reduce the energy threshold to search for low-mass dark matter below 3 GeV/c2, and search for unexpected or “exotic” ways that dark matter might interact with xenon.

“We are in discovery territory, and there is a large swath of physics phenomena that LZ can now access with greater sensitivity,” said Alvine Kamaha, assistant professor at UCLA and the chair of LZ’s institutional board. “In addition to WIMPs and boron-8 solar neutrinos, LZ's exceptional sensitivity also enables the exploration of a broad range of other rare physics processes beyond the Standard Model. This includes the inaugural search for millicharged particles in an underground experiment, the search for cosmic-ray boosted dark matter particles, solar axions, and exotic neutrino interactions with electrons.”

Many of the researchers from LZ are also designing a future dark matter detector that uses liquid xenon on an even larger scale. The XLZD detector will combine the best technologies from projects like LZ, XENONnT, and DARWIN for a next-generation WIMP hunter that can also study neutrinos, the sun, cosmic rays, and other unusual candidates for dark matter, such as dark photons and axion-like particles.

LZ is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics, and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science user facility. LZ is also supported by the Science & Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology; the Swiss National Science Foundation; the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics; and the Institute for Basic Science, Korea. Thirty-seven institutions of higher education and advanced research provided support to LZ. The LZ collaboration acknowledges the assistance of the Sanford Underground Research Facility.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to groundbreaking research focused on discovery science and solutions for abundant and reliable energy supplies. The lab’s expertise spans materials, chemistry, physics, biology, earth and environmental science, mathematics, and computing. Researchers from around the world rely on the lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 17 Nobel Prizes. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

2025-22730 | INT/EXT | Newsroom