"Wombat" Detector Up and Running in Australia

Will enable structural and dynamic studies of materials for electronics, energy conversion, and more

July 28, 2008

enlarge

enlarge

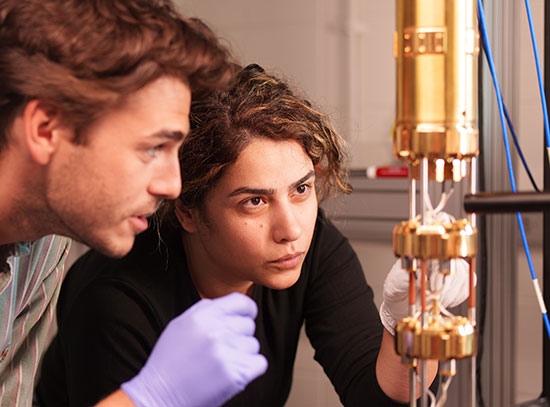

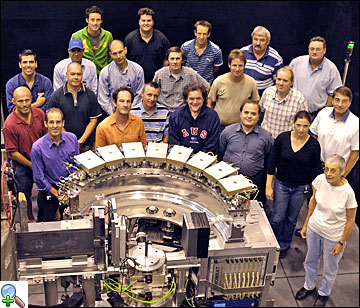

The Australian Nuclear Science & Technology Organization research team gather around their BNL-built detector.

A neutron detector designed and built by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory is now up and running at Australia's new OPAL nuclear research reactor, which is operated by the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization (ANSTO). The detector is a major component of Wombat (named for the native Australian marsupial), one of several new instruments at OPAL. Wombat will soon be collecting data on the properties of a wide range of materials with potential applications in electronics, drug delivery, and energy conversion and storage.

The detector project drew upon the expertise of physicists, engineers, and technical staff within Brookhaven Lab's Instrumentation Division. That team, with mechanical engineering assistance from the Collider-Accelerator Department and support from Central Fabrication Services Division, had designed and built a nearly identical neutron detector for biologists at Los Alamos National Laboratory, where it has been operating successfully for structural studies of proteins since 2002. A visit there prompted a group of Australian scientists to request a similar design.

"It was quite an honor to carry out this work," said Brookhaven physicist Graham Smith, who led the project. "We're not in the business of production-line assembly, but this detector is not something the Australians could have purchased commercially. All the parts are unique and all were designed here at Brookhaven. The Australians came to us because we have a long track record of building one-of-a-kind, precision detectors for research facilities. So we were delighted to do this for the benefit of science."

Brookhaven Lab was compensated through a "work for others" arrangement.

Like its counterpart at Los Alamos, the detector on the Australian Wombat instrument is made of eight identical multi-wire segments arranged side-by-side inside an arc-shaped aluminum pressure vessel containing a rare form of helium gas. As a neutron beam from the OPAL reactor scatters off a sample placed at the center of the arc, neutrons scatter, or diffract, off the sample, travel into the vessel, and collide with helium atoms.

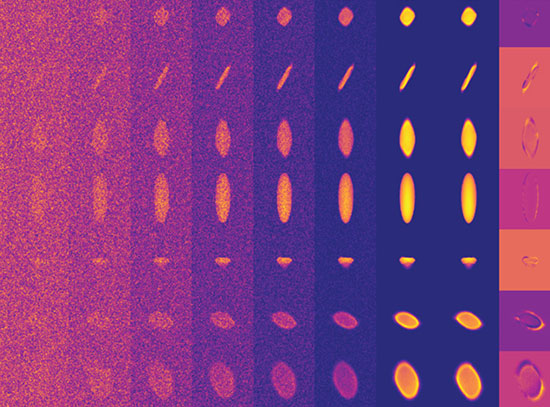

These collisions produce a telltale track of electrons, which are sensed by low-noise electronics sitting on top of the vessel, and translated into a diffraction pattern - a scatter plot of dots that indicate the direction and intensity of the scattered beam. This information enables the experimenter to determine the positions of hydrogen atoms in the sample, which can then be used to piece together important structural details of the sample. By taking several "snapshots" over time, the scientists can also use the detector to make "movies" of how a material's structure changes, for example, when the sample is placed under pressure or when an electric current is applied.

"We've already had a lot of interest in using Wombat for rapid real-time measurements," said ANSTO researcher Andrew Studer. "For example, there's a lot of interest in looking at phase changes in various materials. We've also had interest from chemists who want to look at how hydrogen arranges itself in hydrogen-storage materials as they're being charged up: Where in the structure does it go first? How does it shuffle around as the charging continues? How does the structure change after repeated use? Wombat can answer these sort of questions, which may help lead to better storage solutions."

Although the Wombat detector was the second of its kind built by the Brookhaven team, research and development was carried out to improve its performance from the initial design, primarily upgrades to several electronic elements to increase the rate of data collection.

"It was also a big effort in terms of logistics," Smith said, "even bigger than the detector built for Los Alamos, because everything had to be moved halfway around the world."

All the parts were packaged in crates made by Brookhaven carpenters. "They did an exceptional job," Smith said. "When we unpacked at ANSTO, everything was in perfect condition and worked without a fault."

Instrumentation's Neil Schaknowski and Joe Mead accompanied Smith to Australia in early 2007 for the onsite assembly and instrument commissioning, which went without a hitch. A temporary reactor shutdown then resulted in all OPAL instruments having no neutrons until the reactor came back online in May 2008. Now up and running, Wombat is poised for scattering studies and - the Brookhaven team anticipates - stunning science.

2008-770 | INT/EXT | Newsroom