Metal Deficit in Mouse Brain Plaques Guides Direction of Human Alzheimer’s Disease Research

October 20, 2009

Minuscule plaques in the brains of mice with Alzheimer’s disease contain much less metal than the brains of affected humans, according to a study conducted at the NSLS. This surprising finding could help researchers pinpoint the effect of metal in the human disease, and, in the long term, lead to targets for drug development or prevention methods.

One of the hallmark features of Alzheimer’s diseased brain is amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques, small areas of dense built-up proteins named after a protein they contain. Many scientists believe that these plaques are involved in neurodegeneration – the destruction of brain cells that gradually destroys a person’s ability to learn, reason, communicate, and carry out daily activities.

In previous studies, researchers have found an abundance of zinc, copper, and iron in the amyloid plaques in human Alzheimer’s disease. These metal ions are essential to brain function and present in the body under normal conditions, but elevated levels in the plaques may catalyze the formation of free radicals, which are toxic to brain cells. In studies on mice that were bred to develop Aβ plaques, though, researchers have observed a discrepancy.

“Although the mice are designed to develop one of the features of Alzheimer’s disease, they don’t show severe neurodegeneration, memory deficits, or any of the other terrible things that are associated with human Alzheimer’s disease,” said Stony Brook University graduate student Andreana Leskovjan. That difference might be attributed to a lower concentration of metal in mouse Aβ plaques.

To investigate the possibility that metals might be the cause of one of the disease’s most debilitating symptoms, Leskovjan and her research advisor, Lisa Miller, worked with University of Chicago scientist Tony Lanzirotti to examine the metal content of mouse Aβ plaques.

The researchers used an x-ray fluorescence microscope at NSLS beamline X26A to determine the metal concentration in plaques and surrounding non-plaque tissue taken from mice representing end-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy at beamline U10B also was used to normalize the data for the amount of protein in each plaque. They then compared the metal levels to previously collected data taken from human brains.

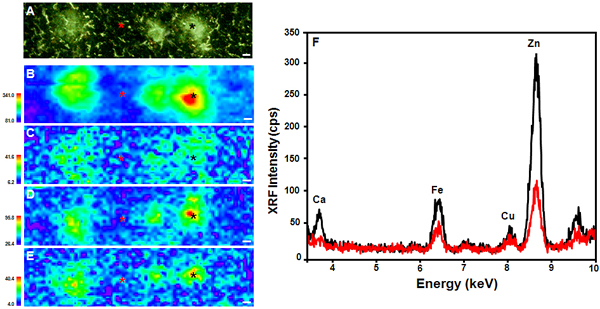

(A) Thioflavin S-stained PSAPP mouse brain tissue. X-ray fluorescence microprobe images of (B) Zn, (C) Cu, (D) Fe, and (E) Ca distribution in the same tissue. (F) XRF microprobe spectra collected from the areas marked with asterisks in (A) – (E), comparing the center of a plaque (black) to the surrounding tissue (red). All scale bars are 5 μm.

Their results were surprising, but important for the Alzheimer’s research field, Leskovjan said. In mice, the plaques only showed an elevation in one type of metal – zinc, up by 29 percent – as compared to the surrounding tissue. But the mouse plaques actually had less copper and iron (about a 22 percent and 17 percent decrease, respectively) than in the surrounding tissue. Human Aβ plaques, by comparison, showed a 339 percent increase in zinc, a 466 percent increase in copper, and a 177 percent increase in iron.

These results were published in the October 1, 2009 edition of the journal NeuroImage.

“Even though the mice don’t match the human results, this study provides some very valuable information,” Leskovjan said. “The metal deficit in mice could actually help us narrow down what’s happening in the brains of human Alzheimer’s disease patients. For instance, maybe the abundance of copper and iron, which aren’t present in mice, could be causing the neurodegeneration that’s seen in humans.”

The mice only provide a limited representation of the human disease, and differences in plaques could be due to a number of factors between the two species, but this study provides a solid path to follow, Leskovjan said.

If metals turn out to be the culprit, further research might lead to the identification of targets for drug development or metal-targeted therapy to remove the excess metals from the plaques.

Now, the researchers are studying the metal concentrations in early-stage Aβ mouse plaques to determine how age affects the levels.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The NSLS is funded by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences within the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

2009-1470 | INT/EXT | Newsroom