LI High School Students Solve Protein Structures at Brookhaven's Light Source

Knowledge gained at world-class research facility could open doors to new treatments for diseases and advance careers of young scientists

December 18, 2019

enlarge

enlarge

Shelter Island High School students Lauren Gurney and Emma Gallagher with a 3-D model of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), a protein involved in a range of diseases whose structure the students solved using x-rays at Brookhaven Lab's National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II, experimental floor in background).

Students from Long Island, New York, high schools have collaborated across districts to decipher the atomic-level structures of two proteins involved in a variety of diseases. The students used very bright x-rays at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II)—a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility at Brookhaven National Laboratory—to identify the 3-D arrangements of atoms that make up functional components of these proteins. These structures have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank, a repository of information accessible to researchers around the world who can use the information to gain a better understanding of the diseases and possibly design new drugs or other treatments.

The students from Shelter Island High School, Connetquot High School, Eastport South Manor Junior-Senior High School, and other districts were participating in a program known as “Student Partnerships for Advanced Research and Knowledge,” or SPARK, run by Brookhaven Lab’s Office of Educational Programs in collaboration with scientists at NSLS-II.

“SPARK brings high school students and their science teachers to the Lab for free access to the Lab’s research facilities—just like the thousands of scientists from around the world who conduct research at Brookhaven every year,” said program coordinator Aleida Perez. “We start them off with a weeklong summer training session where they learn about the capabilities of user facilities like NSLS-II, as well as how to analyze the data. And we give them guidance on how to form a collaboration and write a successful proposal for the research they want to do.”

SPARK proposals, like those submitted by seasoned scientists, are reviewed by a committee of researchers, and only approved projects make it to the experimental floor. Teams whose projects are chosen then work with Brookhaven staff to make the most of the “beamtime” they’ve been granted.

“We share our tools and expertise with SPARK teams to give students and teachers real-world, hands-on research experience,” said John Hill, director of NSLS-II. “Our goal is to ignite their interest in science and the amazing things that happen at Brookhaven Lab, and possibly inspire them to pursue scientific careers and become future users and staff at our facilities.”

enlarge

enlarge

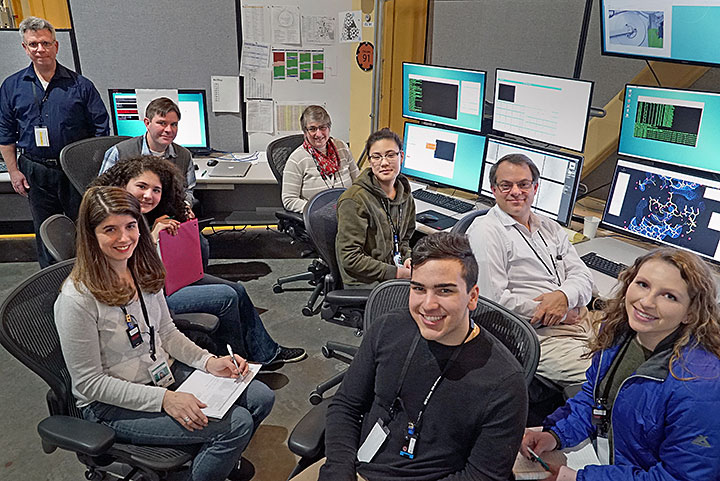

Some of the SPARK students and teachers with Brookhaven Lab staff at NSLS-II's AMX beamline: Standing in back: Dan Williams (Shelter Island High School teacher); clockwise from lower left: Kimberly Collins (Northport High School teacher), Danielle Levanti (Northport), John Halloran (Connetquot High School teacher), Vivian Stojanoff (NSLS-II), Yoora Cho (Northport), Alex Soares (NSLS-II), Giavana Prucha and Christopher Picchiello (both of Connetquot).

Shelter Islanders SPARKed

The Shelter Island project, initiated by Francesa Frasco and later joined by Emma Gallagher and Lauren Gurney, sought to explore the “active site” of a mutant version of a common enzyme (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, or MTHFR) that is involved in many metabolic reactions. The active site of an enzyme determines how it interacts with other molecules. Identifying differences between the mutant and normal enzymes could help scientists understand the mutation’s role in a variety of conditions from recurrent pregnancy loss and a common birth defect to neuropsychiatric diseases and cancer.

“The hope was that by understanding changes in the active site, better treatments for MTHFR diseases might be designed,” said Dan Williams, a New York State master teacher at the Shelter Island school.

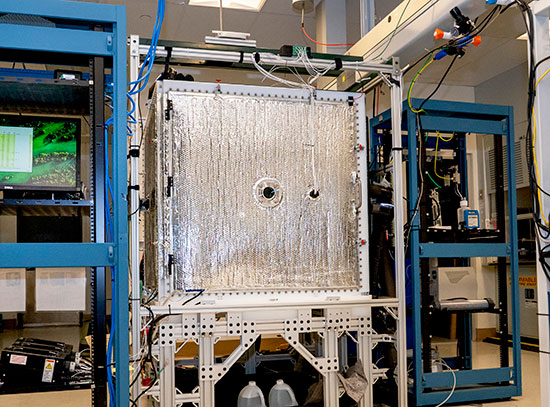

Frasco, Gallagher, and Gurney grew crystals of the protein and harvested them for studies at NSLS-II. They and student collaborators from other districts collected and analyzed data from NSLS-II’s Highly Automated Macromolecular Crystallography (AMX) beamline, which produces diffraction patterns based on how x-rays interact with the protein’s 3-D structure. Additional measurements revealed other details of the enzyme.

enlarge

enlarge

A poster celebrating the success of SPARK and the protein structures solved by students at Connetquot, Northport, and Eastport South Manor high schools (tRNA methyltransferase, or TrmD, left) and Shelter Island High School (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR, right).

The project “gave me real hands-on experience working with a team on a significant project,” Frasco said.

Data analysis took a whole year with students learning from other students and Brookhaven scientists—including Alex Soares and Vivian Stojanoff of NSLS-II, and Seetharaman Jayaraman (no longer at Brookhaven)—who taught them how to use a structural biology modeling program to make sense of their data.

Through these experiments the student scientists discovered a slight change in chemistry at the mutant enzyme’s active site—a swap of one amino acid for another usually found in the wild-type enzyme. The switch explained the protein’s altered binding affinity in key metabolic reactions.

“This collaborative effort—from setting up crystallization plates on Saturdays at Brookhaven, harvesting crystals after school, and beamtime at NSLS-II—has been incredibly rewarding for our students,” Williams said. “They’ve developed skills they would never have had the opportunity to develop in the traditional classroom setting.”

Gallagher agrees. “This project challenged me. It showed me that real scientific achievements can take a very long time to accomplish, and even then, there are always more questions to be asked.”

“I remember all the times where our team got stuck,” Gurney added. “We just kept trying and we'd break through with trial and error and hard work.”

Connetquot/Eastport South Manor collaborators

A second group worked with Stojanoff and Soares on a project initiated by Connetquot High School students Giavana Prucha and Christopher Picchiello along with their teacher, John Halloran. Eastport South Manor students Jason Caesar, Maximilian Carson, Damien Edele, and Christopher Jannotta, along with Danielle Levanti of Northport High School, carried on with the project.

This group set out to determine the complete sequence of an enzyme found in the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum. This microbe has been implicated in a tick-borne disease and bacteria with similar enzymes may contribute to other illnesses.

“A high-resolution structure of this enzyme (tRNA methyltransferase, or TrmD) might serve as a target for developing antibiotics against this pathogen,” said Robert Bolen, a New York State master teacher of advanced placement biology at Eastport South Manor, who noted that interest in developing such drugs has been heightened by an increase in cases of tick-borne illnesses on Long Island. “Recent research has shown that this enzyme may play a role in resistance to antibiotics, so inhibiting its activity might also be a way to increase the effectiveness of current treatments,” he said.

Shelter Island High School student Lauren Gurney chronicled her research experience at Brookhaven Lab in this video blog.

The structure of TrmD solved by these students using the AMX beamline at NSLS-II included the sequence of amino acids that make up a flexible linker region between two lobes of the protein, as well as a flexible halo region in one of the lobes, that each may serve as new targets for the development of inhibitor drugs.

“The collaborative effort to elucidate the structure of this protein spans two years of work by students and teachers from different school districts working on different aspects of the project from crystallization to harvesting and data collection at NSLS-II,” Bolen noted. “The greatest body of work was focused on the careful analysis of the copious amounts of data procured during beamtime data collection.”

Damien Edele and Christopher Jannotta are continuing their work on the project and sharing the skills they’ve developed.

“This structural biology research was all about applying science to the real world,” Jannotta said. “I’ve always loved science and I continue participating so I can help others learn the skills I did, and so I can continue doing what I love with a supportive team of caring and hard-working people.”

Edele also noted the value of “the teamwork, camaraderie, and knowing that we are working our hardest to make even the smallest effect on the scientific community—and knowing that one day I can use these skills in the future when I am a scientist myself.”

Perez, who coordinates SPARK for Brookhaven, says these are exactly the goals of the program—“engaging students in relevant research, complementing their curriculum content, and motivating them to consider careers in STEM.”

“I love this part of what I do, collaborating with the students and teachers,” she said.

The SPARK program and operations of NSLS-II are funded by the DOE Office of Science. The AMX beamline at NSLS-II is funded by the Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health. Future SPARK projects may take place at other Brookhaven Lab user facilities. Several of the students named in this story have since graduated from high school and are now enrolled in universities across the country.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://www.energy.gov/science/

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook

2019-16876 | INT/EXT | Newsroom