Coming Out is a Lifelong Process

CFN's Sara E. Mason explains the need to constantly explain—and what can help change that

June 22, 2023

enlarge

enlarge

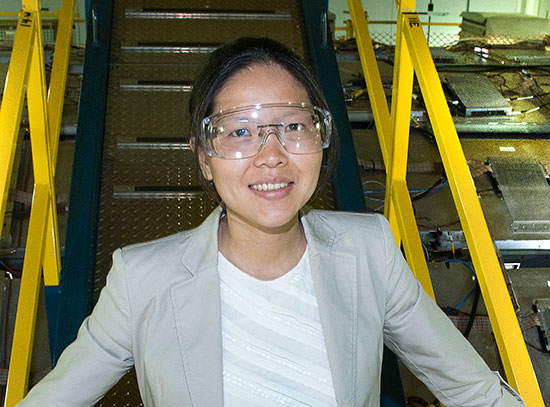

Sara E. Mason, Group Leader in Theory and Computation at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials

When Pride Month comes to mind, a flood of familiar images tends to take hold. Parades, celebrations of LGBTQ+ culture, and rainbows as far as the eye can see—but those only account for what is visible on the surface. Beneath the fanfare, there is a vast pool of personal connections and experiences that is as deep as it is wide. Some members of the Pride community remember a time where big, important parts of their lives needed to be hidden. Now, they can celebrate how far they’ve come to live authentically and proudly. Others are watching from the sidelines, waiting for the right moment to come out. Hope for a fair, better future weaves through the history of a long and often difficult past. There is no monolithic “queer experience” that lays out a simple path to follow, and the resilience and strength of each individual in this diverse community is something to have a lot of pride in.

Sara E. Mason is a group leader in theory and computation at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory. Mason is also an adjunct associate professor at the University of Iowa, a mentor, a parent, and a spouse, among many other things. There is a misconception that orientation and identity are purely personal, as they touch so many interconnected aspects of life. Recently joining the Lab and relocating to New York, Mason has had to work hard to reconnect all those ties while building new relationships and routines.

“In media, you‘ll see that someone came out of the closet, and it will play out like a one-time thing. In actuality, it is a constant process and it can be exhausting,” explained Mason. “It can be something as small as someone seeing my wedding ring and asking about my ‘husband.’ Every moment like that, I have a choice. Is it worth it to give everyone a mini thesis about my life? Do I just shrug it off and continue? It’s in those moments that I realize how much representation matters. The more we normalize the different shapes relationships and families can take, and the more we all start to speak more inclusively, it takes that exhausting burden off of one group to constantly explain and educate others in nearly every situation, even small talk.”

The history of the western nuclear family as the norm is not a long one, emerging and solidifying itself in the 20th century, but it is one that is deeply engrained in American culture and the human psyche. It’s not an easy trope to unravel, but recognizing and leaving behind unconscious assumptions can make a world of difference.

“My children share my last name, but my spouse has a different last name and things like that require a lot of explanation. My wife works from home right now and is pretty close to the school, so it made sense to make her the first point of contact at school. If one of the kids gets a fever and needs to be picked up, when someone sees two femme-identified names and only one matches the kid's last name, who do you think they end up calling? It sounds like a little thing, but constantly needing to reexplain after designating a contact adds up, along with every other misunderstanding in other areas of life. It can feel like the sting of several papercuts.”

In the same way one would study nanostructures and complex materials, Mason was able to probe these feelings and experiences, learn a lot from them, and publish the results to inspire others. Some of these insights were distilled into a chapter of a Springer publication called “Mom the Chemistry Professor” that delved into how personal family lives play into professional lives.

“At the time, I was writing from a very tough place in life,” recalled Mason. “Being an assistant professor and having a queer identity was hard enough, struggling with infertility and being on the tenure track—it was a lot to handle at once. It was important to write about though. When I felt like no one understood what I was going through, it emphasized how much representation matters.”

Representation is one way people and organizations can help take the onus off LGBTQ+ people. By showcasing a rich variety of relationships, family structures, gender expressions, and identities, moving beyond preconceived notions becomes easier. By making the world shown in media reflect diverse, real-world communities, more of society can feel a sense of belonging, instead of just the perceived majority.

While individuals can do a lot to lift up those around them and help to develop a culture of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility, larger organizations and institutions can make a significant impact. This can be through making forms and policies more inclusive, by modifying constrictive language, by providing educational resources that take the responsibility off of individuals, and by promoting an inclusive culture where people don’t feel like outliers.

Mason was optimistic about the role the STEM community could play in a better future for the LGBTQ+ community. “If anyone can really make advances in this, I'm so optimistic that scientists are the ones who can. We learn the newest information and we adjust our thinking. If a new theory came out that disproved everything we've been doing, while we might be rattled by that, we would pick up the pieces and move forward from there.”

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2023-21291 | INT/EXT | Newsroom