New Insights into Nanoplate Self-Assembly

February 11, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

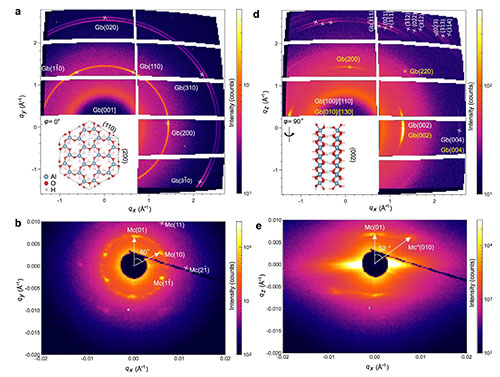

(a/b) WAXS/SAXS patterns with the mesocrystal placed in the x-y plane and the X-ray beam oriented perpendicular to the gibbsite lattice index plane. (d/e) WAXS/SAXS patterns with the mesocrystal placed in the y–z plane and the X-ray beam parallel to the gibbsite lattice index plane.

The Science

Researchers demonstrate how gibbsite nanoplates self-assemble into larger, ordered “mesocrystals” by sliding into a stable, staggered arrangement rather than perfectly aligning.

The Impact

These findings reveal how atomic-scale forces influence macroscopic mesocrystal structure, which could help design better materials made by particle attachment.

Summary

Oriented attachment is a crystal growth process in which nanocrystals self-assemble along specific crystallographic directions to form larger structures, like “mesocrystals.” Although this process plays an important role in geochemical, biomineral, and synthetic material systems, its underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Earlier research largely focused on the forces that help particles line up their crystal structures, but it was still unclear what forces control how they stack evenly into larger, ordered structures.

To address this, a research collaboration between the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, and Brookhaven National Laboratory studied how tiny, flat gibbsite nanoplates self-assemble into much larger mesocrystals. To start, the nanoplates were synthesized with uniform dimensions (~93 nm wide and ~9.5 nm thick) and left sealed and undisturbed in deionized water at room temperature for six months. In that time, the particles settled into a sediment of flake-like aggregates ranging from a few micrometers to several hundred micrometers in size. When examined under a polarized-light microscope, these aggregates exhibited regions of shared orientation, indicating that the nanoplates within each region were partially ordered rather than randomly oriented.

Using a combination of in situ liquid-cell transmission electron microscopy, X-ray scattering, electron microscopy, and molecular dynamics simulations, the team directly observed and modeled how individual nanoplates attach. They found that attachment occurs in two distinct steps: a rapid rotation or jump that brings the basal planes into contact, followed by a directional sliding motion that increases the area of overlap. This sliding is strongly favored along one crystallographic direction, leading to a regular, staggered stacking arrangement. Simulations revealed that this offset configuration is energetically more stable than perfect alignment and that sliding in the preferred direction requires less energy. The models also showed that water molecules at the particle surfaces play a critical role in mediating interactions, enabling the nanoplates to organize over long distances. Wide- and small-angle X-ray scattering experiments were performed at the Complex Materials Scattering beamline at NSLS-II to understand the long-range order of a single aggregate and how it links to the crystallographic orientation of the nanoplates.

Together, these results show that crystal growth by oriented attachment is governed by an underlying energy landscape, not just by particle alignment. This improved understanding helps explain how complex, hierarchical structures form in nature and could guide the design of new materials with architectures promoting desired properties.

Download the research summary slide (PDF)

Related Links

Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64852-7

Contact

Kevin M. Rosso

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

kevin.rosso@pnnl.gov

Xin Zhang

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

xin.zhang@pnnl.gov

Publications

Xiaoxu Li, Tuan A. Ho, Honghu Zhang, Lili Liu, Ruipeng Li, Ping Chen, Mark E. Bowden, Sebastian T. Mergelsberg, Hongyou Fan, James J. De Yoreo, Carolyn I. Pearce, Kevin M. Rosso, & Xin Zhang. Mesocrystal growth through oriented sliding and attachment of nanoplates. Nat Commun 16, 11240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64852-7

Funding

This material is based on work supported by the Ion Dynamics in Radioactive Environments and Materials (IDREAM) program, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (FWP 68932). X.L., C.P., D.J.J., K.M.R., and X.Z. also acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division through its Geosciences Program at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) (FWP 56674). PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated by Battelle Memorial Institute under contract no. DE-AC05-76RL01830 for the DOE. T.A.H. acknowledges support by the DOE Office of Science, BES, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division through its Geosciences Program at Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) (FWP 24-015452). This article was authored by an employee of National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC, under contract no. DE-NA0003525 with the US DOE. This research also utilized the Complex Materials Scattering (CMS, 11-BM) beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated by the DOE Office of Science at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. A portion of the work was carried out in the Environmental and Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL), a national scientific user facility at PNNL sponsored by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under user proposals 10.46936/lser.proj.2020.51382/60000186 and 10.46936/lser.proj.2021.51922/60000373.

2026-22833 | INT/EXT | Newsroom