Unstoppable Magnetoresistance

October 14, 2014

By Tien Nguyen

enlarge

enlarge

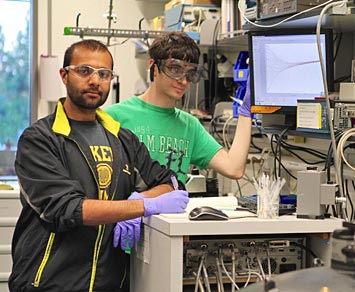

Mazhar Ali (left) and Steven Flynn (right), co-authors on the Nature article

Photo credit: C. Todd Reichart

This feature story was written by Tien Nguyen, a communications specialist in the Department of Chemistry at Princeton University, about research done in partnership with Jing Tao, a scientist in the Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science Department at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Mazhar Ali, a fifth-year graduate student in the laboratory of Bob Cava, the Russell Wellman Moore Professor of Chemistry at Princeton University, has spent his academic career discovering new superconductors, materials coveted for their ability to let electrons flow without resistance. While testing his latest candidate, the semimetal tungsten ditelluride (WTe2), he noticed a peculiar result.

Ali applied a magnetic field to a sample of WTe2, one way to kill superconductivity if present, and saw that its resistance doubled. Intrigued, Ali worked with Jun Xiong, a student in the laboratory of Nai Phuan Ong, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics at Princeton, to re-measure the material’s magnetoresistance, which is the change in resistance as a material is exposed to stronger magnetic fields.

“They have unique capabilities at Brookhaven. One is that they can measure diffraction at 10 Kelvin (-441 °F).”

— Bob Cava, Princeton University

“He noticed the magnetoresistance kept going up and up and up—that never happens.” said Cava. The researchers then exposed WTe2 to a 60-tesla magnetic field, close to the strongest magnetic field mankind can create, and observed a magnetoresistance of 13 million percent. The material’s magnetoresistance displayed unlimited growth, making it the only known material without a saturation point. The results were published on September 14 in the journal Nature.

Electronic information storage is dependent on the use of magnetic fields to switch between distinct resistivity values that correlate to either a one or a zero. The larger the magnetoresistance, the smaller the magnetic field needed to change from one state to another, Ali said. Today’s devices use layered materials with so-called “giant magnetoresistance,” with changes in resistance of 20,000 to 30,000 percent when a magnetic field is applied. “Colossal magnetoresistance” is close to 100,000 percent, so for a magnetoresistance percentage in the millions, the researchers hoped to coin a new term.

Their original choice was “ludicrous” magnetoresistance, which was inspired by “ludicrous speed,” the fictional form of fast-travel used in the comedy “Spaceballs.” They even included an acknowledgement to director Mel Brooks. After other lab members vetoed “ludicrous,” the researchers considered “titanic” before Nature editors ultimately steered them towards the term “large magnetoresistance.”

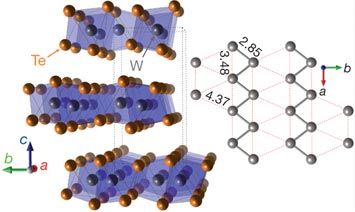

Terminology aside, the fact remained that the magnetoresistance values were extraordinarily high, a phenomenon that might be understood through the structure of WTe2. To look at the structure with an electron microscope, the research team turned to Jing Tao, a researcher at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

“Jing is a great microscopist. They have unique capabilities at Brookhaven,” Cava said. “One is that they can measure diffraction at 10 Kelvin (-441 °F). Not too many people on Earth can do that, but Jing can.”

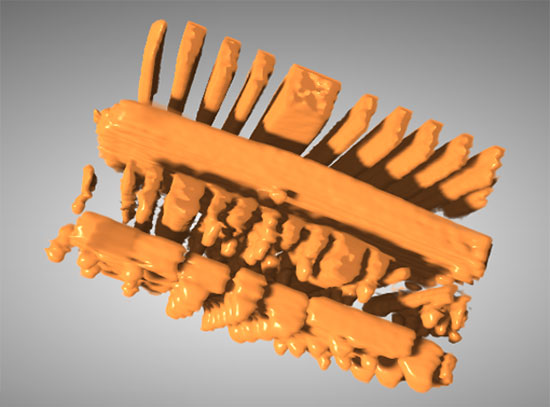

Electron microscopy experiments revealed the presence of tungsten dimers, paired tungsten atoms, arranged in chains responsible for the key distortion from the classic octahedral structure type. The research team proposed that WTe2 owes its lack of saturation to the nearly perfect balance of electrons and electron holes, which are empty docks for traveling electrons. Because of its structure, WTe2 only exhibits magnetoresistance when the magnetic field is applied in a certain direction. This could be very useful in scanners, where multiple WTe2 devices could be used to detect the position of magnetic fields, Ali said.

“Aside from making devices from WTe2, the question to ask yourself as a scientist is: How can it be perfectly balanced, is there something more profound,” Cava said.

2014-5262 | INT/EXT | Newsroom