Startup Time for Ion Collisions Exploring the Phases of Nuclear Matter

19th year of operations at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider will continue search for critical point in transition from protons and neutrons to quark-gluon plasma.

January 4, 2019

enlarge

enlarge

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) is actually two accelerators in one. Beams of ions travel around its 2.4-mile-circumference rings in opposite directions at nearly the speed of light, coming into collision at points where the rings cross.

UPTON, NY—January 2 marked the startup of the 19th year of physics operations at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Physicists will conduct a series of experiments to explore innovative beam-cooling technologies and further map out the conditions created by collisions at various energies. The ultimate goal of nuclear physics is to fully understand the behavior of nuclear matter—the protons and neutrons that make up atomic nuclei and those particles’ constituent building blocks, known as quarks and gluons.

enlarge

enlarge

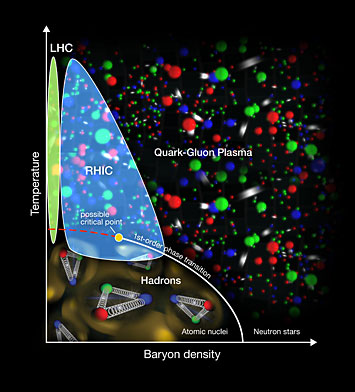

The STAR collaboration's exploration of the "nuclear phase diagram" so far shows signs of a sharp border—a first-order phase transition—between the hadrons that make up ordinary atomic nuclei and the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) of the early universe when the QGP is produced at relatively low energies/temperatures. The data may also suggest a possible critical point, where the type of transition changes from the abrupt, first-order kind to a continuous crossover at higher energies. New data collected during this year's run will add details to this map of nuclear matter's phases.

Many earlier experiments colliding gold ions at different energies at RHIC have provided evidence that energetic collisions create extreme temperatures (trillions of degrees Celsius). These collisions liberate quarks and gluons from their confinement with individual protons and neutrons, creating a hot soup of quarks and gluons that mimics what the early universe looked like before protons, neutrons, or atoms ever formed.

“The main goal of this run is to turn the collision energy down to explore the low-energy part of the nuclear phase diagram to help pin down the conditions needed to create this quark-gluon plasma,” said Daniel Cebra, a collaborator on the STAR experiment at RHIC. Cebra is taking a sabbatical leave from his position as a professor at the University of California, Davis, to be at Brookhaven to help coordinate the experiments this year.

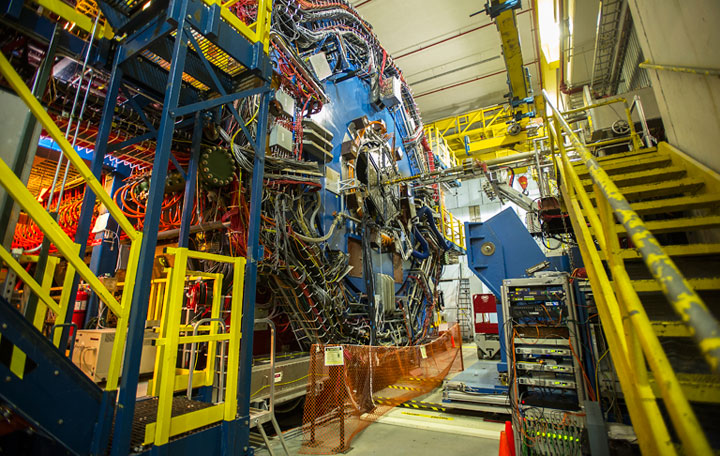

STAR is essentially a house-sized digital camera with many different detector systems for tracking the particles created in collisions. Nuclear physicists analyze the mix of particles and characteristics such as their energies and trajectories to learn about the conditions created when ions collide.

By colliding gold ions at various low energies, including collisions where one beam of gold ions smashes into a fixed target instead of a counter-circulating beam, RHIC physicists will be looking for signs of a so-called “critical point.” This point marks a spot on the nuclear phase diagram—a map of the phases of quarks and gluons under different conditions—where the transition from ordinary matter to free quarks and gluons switches from a smooth one to a sudden phase shift, where both states of matter can coexist.

STAR gets a wider view

STAR will have new components in place that will increase its ability to capture the action in these collisions. These include new inner sectors of the Time Projection Chamber (TPC)—the gas-filled chamber particles traverse from their point of origin in the quark-gluon plasma to the sensitive electronics that line the inner and outer walls of a large cylindrical magnet. There will also be a “time of flight” (ToF) wall placed on one of the STAR endcaps, behind the new sectors.

“The main purpose of these is to enhance STAR's sensitivity to signatures of the critical point by increasing the acceptance of STAR—essentially the field of view captured in the pictures of the collisions—by about 50 percent,” said James Dunlop, Associate Chair for Nuclear Physics in Brookhaven Lab’s Physics Department.

enlarge

enlarge

RHIC's STAR detector tracks the thousands of particles produced by each ion collision. It weighs 1,200 tons and is as large as a house.

“Both of these components have large international contributions,” Dunlop noted. “A large part of the construction of the iTPC sectors was done by STAR’s collaborating institutions in China. The endcap ToF is a prototype of a detector being built for an experiment called Compressed Baryonic Matter (CBM) at the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) in Germany. The early tests at RHIC will allow CBM to see how well the detector components behave in realistic conditions before it is installed at FAIR while providing both collaborations with necessary equipment for a mutual-benefit physics program,” he said.

Tests of electron cooling

enlarge

enlarge

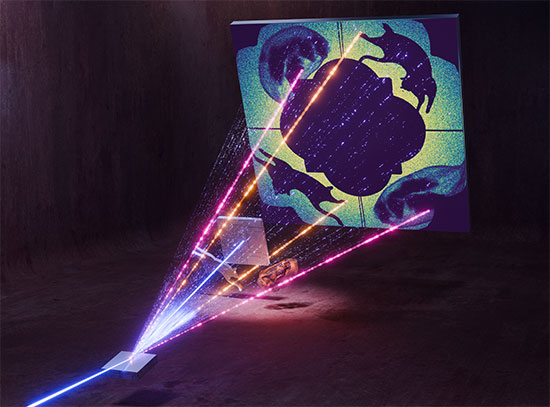

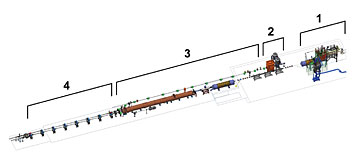

A schematic of low-energy electron cooling at RHIC, from right: 1) a section of the existing accelerator that houses the beam pipe carrying heavy ion beams in opposite directions; 2) the direct current (DC) electron gun and other components that will produce and accelerate the bright beams of electrons; 3) the line that will transport and inject cool electrons into the ion beams; and 4) the cooling sections where ions will mix and scatter with electrons, giving up some of their heat, thus leaving the ion beam cooler and more tightly packed.

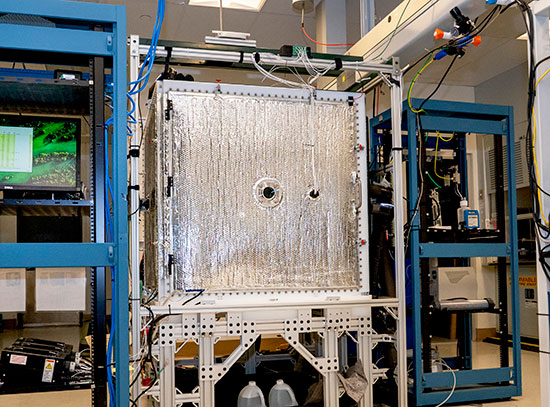

Before the collision experiments begin in mid-February, RHIC physicists will be testing a new component of the accelerator designed to maximize collision rates at low energies.

“RHIC operation at low energies faces multiple challenges, as we know from past experience,” said Chuyu Liu, the RHIC Run Coordinator for Run 19. “The most difficult one is that the tightly bunched ions tend to heat up and spread out as they circulate in the accelerator rings.”

That makes it less likely that an ion in one beam will strike an ion in the other.

To counteract this heating/spreading, accelerator physicists at RHIC have added a beamline that brings accelerated “cool” electrons into a section of each RHIC ring to extract heat from the circulating ions. This is very similar to the way the liquid running through your home refrigerator extracts heat to keep your food cool. But instead of chilled ice cream or cold cuts, the result is more tightly packed ion bunches that should result in more collisions when the counter-circulating beams cross.

Last year, a team led by Alexei Fedotov demonstrated that the electron beam has the basic properties needed for cooling. After a number of upgrades to increase the beam quality and stability further, this year’s goal is to demonstrate that the electron beam can actually cool the gold-ion beam. The aim is to finish fine-tuning the technique so it can be used for the physics program next year.

Berndt Mueller, Brookhaven’s Associate Laboratory Director for Nuclear and Particle Physics, noted, “This 19th year of operations demonstrates once again how the RHIC team — both accelerator physicists and experimentalists — is continuing to explore innovative technologies and ways to stretch the physics capabilities of the most versatile particle accelerator in the world.”

Research at RHIC is funded primarily by the DOE Office of Science (NP) and by these agencies and organizations.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2019-13302 | INT/EXT | Newsroom