MicroBooNE Finds no Evidence for a Sterile Neutrino

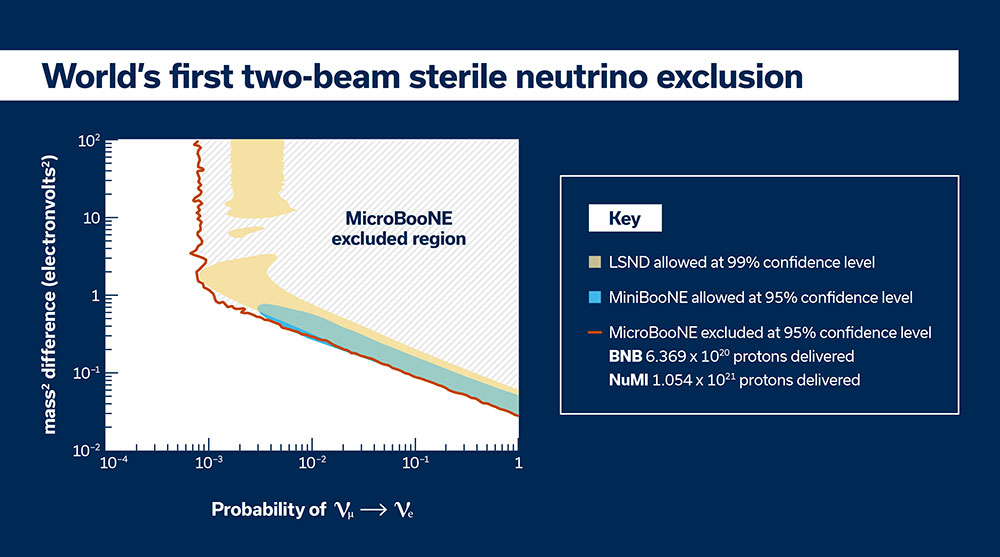

Scientists on the MicroBooNE experiment further ruled out the possibility of one sterile neutrino as an explanation for results from previous experiments. In the latest MicroBooNE result, the collaboration used one detector and two beams to study neutrino behavior, ruling out the single sterile neutrino model with 95% certainty.

December 3, 2025

enlarge

enlarge

Previous experiments indicated where a fourth neutrino may be observed. MicroBooNE scientists have ruled out the region where a single sterile neutrino may have been found with 95% certainty. The collaboration combined data collected from two different neutrino beams to achieve this result. Credit: MicroBooNE collaboration

Editor’s note: The following news release about the search for evidence of sterile neutrinos by the MicroBooNE experiment was originally issued by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, where the MicroBooNE experiment is located. Scientists from DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory have made major contributions to this experiment and to developing the capabilities needed for the newly published results. For more information about Brookhaven’s role in this work, see the related Brookhaven Lab feature article, or contact Karen McNulty Walsh, kmcnulty@bnl.gov, (631) 344-8350.

Scientists are closing the door on one explanation for a neutrino mystery that has plagued them for decades.

An international collaboration of scientists working on the MicroBooNE experiment at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory announced that they have found no evidence for a fourth type of neutrino. The paper was published today in Nature.

Earlier physics experiments saw neutrinos behaving in a way inconsistent with the Standard Model of particle physics. Theorists have suggested that a sterile neutrino could explain those anomalies. However, with this new result, MicroBooNE has been able to rule out a single sterile neutrino explanation with 95% certainty.

The Standard Model is the best theory scientists have for explaining how the universe works. However, it is incomplete.

“We know that the Standard Model does a great job describing a host of phenomena in the natural world,” said Matthew Toups, Fermilab senior scientist and co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE. “And at the same time, we know it’s incomplete. It doesn’t account for dark matter, dark energy or gravity.”

So, physicists are on the hunt for new physics that may shed light on some of the biggest mysteries in the universe.

Neutrinos are tantalizing particles when it comes to searches for new physics because so many questions surround these ghostly particles. One mystery in particular has haunted physicists for decades.

According to the Standard Model there are three types, or flavors, of neutrino: muon, electron and tau. Neutrinos oscillate between these flavors, changing, for instance, from a muon neutrino to an electron neutrino or to a tau neutrino. Scientists have been studying how neutrinos oscillate between these flavors for decades, giving them a strong foundation for understanding how often neutrinos are supposed to change flavor.

The first suggestion that something unexpected may be occurring when neutrinos oscillate was observed by the Liquid Scintillator Neutrino Detector (LSND) at Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1995. Fermilab’s MiniBooNE experiment was initiated to verify those results. Both LSND and MiniBooNE made observations suggesting that muon neutrinos were oscillating into electron neutrinos over shorter distances than are possible with only three neutrino flavors.

“They saw flavor change on a length scale that is just not consistent with there only being three neutrinos,” explained Justin Evans, professor at the University of Manchester and co-spokesperson for MicroBooNE. “And the most popular explanation over the past 30 years to explain the anomaly is that there’s a sterile neutrino.”

Although neutrinos aren’t known for being particularly social particles, they do occasionally interact with matter via the weak force. For there to be an undiscovered neutrino it would have to be even less interactive. In the case of a sterile neutrino, this hypothetical particle would only interact via gravity.

“MicroBooNE is finally closing the chapter on one of the strongest explanations over the past few decades for those anomalies,” said Nitish Nayak, a postdoctoral research associate at Brookhaven National Laboratory and collaborator on the MicroBooNE experiment.

enlarge

enlarge

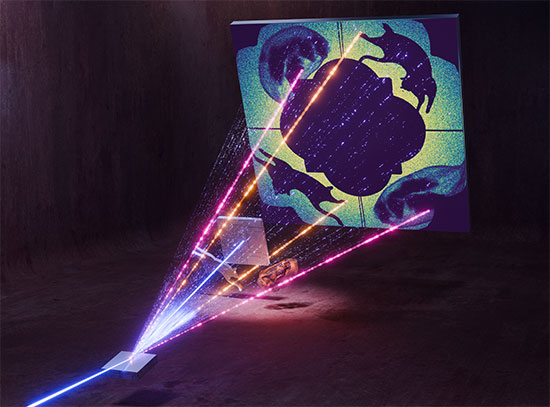

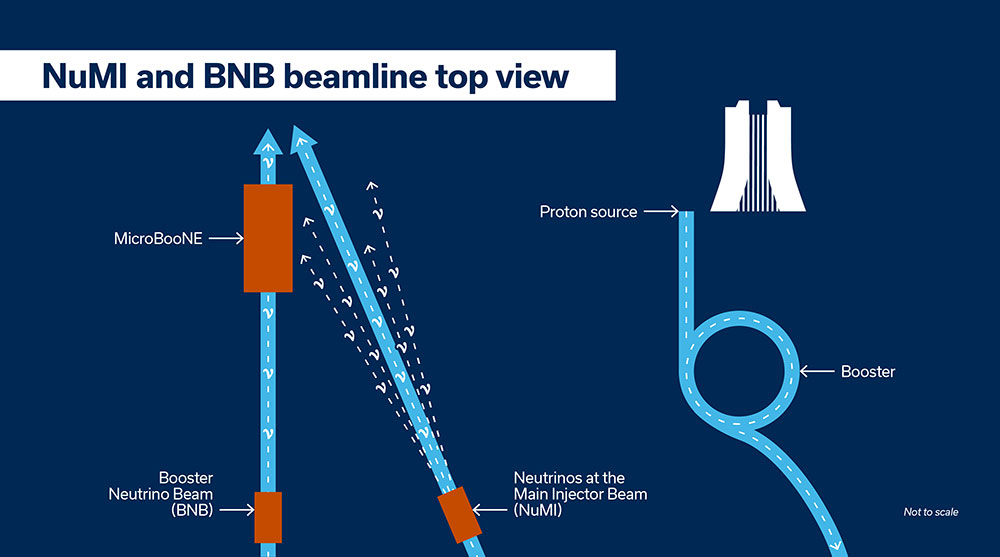

For this result, MicroBooNE observed neutrinos from both the Booster Neutrino Beam (BNB) and NuMI. Credit: Samantha Koch, Fermilab

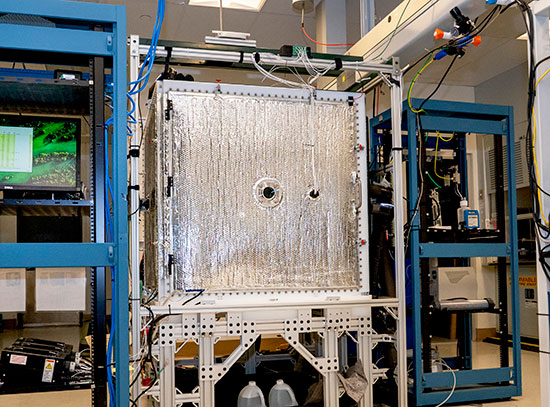

MicroBooNE, a liquid-argon time projection chamber experiment, sits along the Booster Neutrino Beam (BNB), just 70 meters in front of where MiniBooNE measured the anomaly. From that position, MicroBooNE observed neutrino interactions from the BNB and from another neutrino beam at Fermilab, NuMI. MicroBooNE collected data from 2015 to 2021.

“MicroBooNE is the first experiment that has done a sterile neutrino search with one detector and two beams simultaneously,” said Sergey Martynenko a research associate at Brookhaven Lab and collaborator on the MicroBooNE experiment.

Observing neutrinos from both beams reduced the uncertainties in MicroBooNE’s result, making it possible to exclude nearly the entire favored region in which a single sterile neutrino could be hiding.

“It’s really exciting to be doing both cutting-edge science that has a major impact on our field as well as developing novel techniques that will support and enable future scientific measurements,” said Toups.

In addition to continuing to search for new physics, the MicroBooNE collaboration is providing insight into how neutrinos interact in liquid argon, an important metric that will benefit other liquid-argon time projection chamber experiments such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment.

enlarge

enlarge

Members of the MicroBooNE collaboration pose in front of Wilson Hall with a 3D-printed model of the MicroBooNE detector. The collaboration consists of 193 scientists from 40 institutions. Credit: Dan Svoboda, Fermilab

Although one explanation for the anomalies seen by MiniBooNE and LSND has been ruled out, the mystery still remains.

This result used just 60% of MicroBooNE’s total data set and scientists are already beginning to sift through the rest. And MicroBooNE isn’t the only collaboration on the case.

The Short-Baseline Neutrino Program adds a powerful multi-detector approach with a near detector and a far detector to determine whether a more complicated model could explain the LSND and MiniBooNE anomalies. ICARUS, the far detector in the program, began taking beam data at Fermilab in 2021 and the Short-Baseline Near Detector (SBND) started data in 2024.

“Any time you rule out one place where physics beyond the Standard Model could be, that makes you look in other places,” said Evans. “This is a result that is going to really spur a creative push in the neutrino physics community to come up with yet more exciting ways of looking for new physics.”

The international MicroBooNE collaboration is hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The collaboration consists of 193 scientists from 40 institutions including national labs and universities from six countries.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory is America’s premier national laboratory for particle physics and accelerator research. Fermi Forward Discovery Group manages Fermilab for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. Visit Fermilab’s website at www.fnal.gov and follow us on social media.

2025-22312 | INT/EXT | Newsroom