Two Beams, One Detector, Most Precise Search for 'Sterile' Neutrinos

Brookhaven Lab team led approach and analysis of results

December 3, 2025

enlarge

enlarge

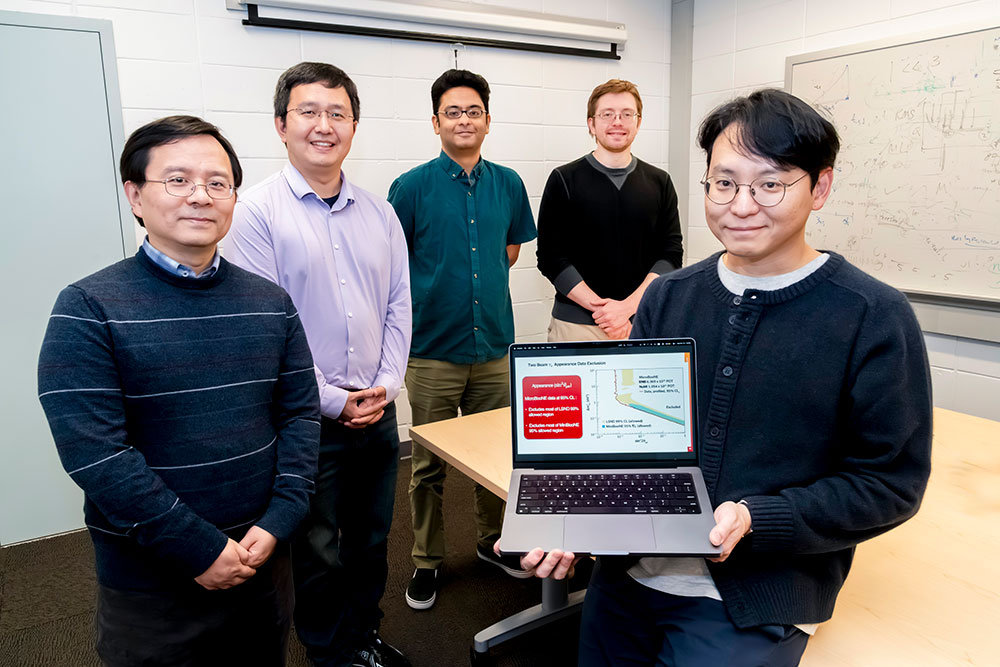

Brookhaven National Laboratory neutrino hunters Chao Zhang, Xin Qian, Bannanje Nitish Nayak, Sergey Martynenko, and Jay Hyun Jo display the latest result from the MicroBooNE experiment at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. The Brookhaven team led the development of the two-beam approach and the overall scientific analysis that enabled this result. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

In the search for evidence of a ghostly particle called the “sterile” neutrino, the latest results from the MicroBooNE detector at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) are a big deal. The results rule out the possibility that a fourth neutrino type could explain anomalous results observed by earlier neutrino-hunting experiments.

“This is the first time a single experiment has been able to rule out the type of sterile neutrino hypothesized to explain results from the Liquid Scintillator Neutrino Detector (LSND) and the MiniBooNE detector, and it was done with a high degree of precision,” said Jay Hyun Jo, a physicist at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and member of the MicroBooNE collaboration.

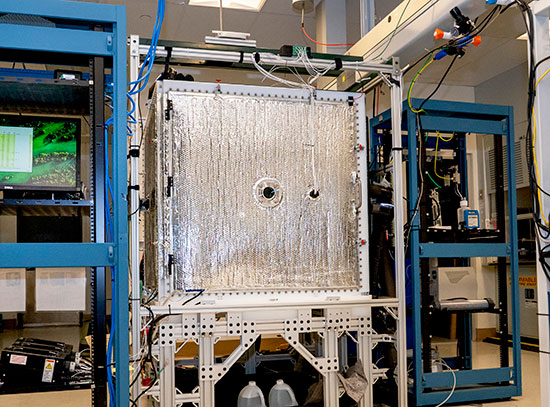

Scientists from Brookhaven have been involved in all aspects of the MicroBooNE experiment since its inception. The detector was originally conceived to look for excess events in the ghostlike transformations among three known neutrino types, or “flavors.” Those excesses hinted there might be a fourth, extra-elusive neutrino variety. MicroBooNE’s original analysis used the same Fermilab booster neutrino beam where MiniBooNE had observed excess events.

“We did not find the excess so that could have been the end of the story,” Jo said.

enlarge

enlarge

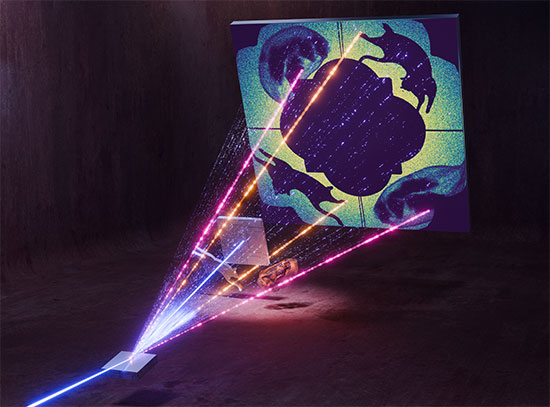

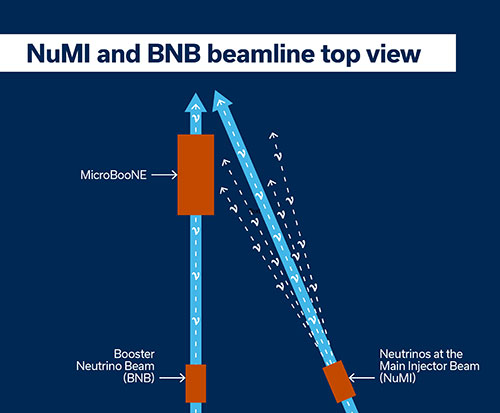

One detector, two beams: In addition to seeing neutrinos (ν) produced by Fermilab's Booster Neutrino Beam, the MicroBooNE detector also captures neutrinos from a slice of the NuMI beam as it travels to faraway targets such as the NOvA and MINOS experiments. By comparing how neutrinos from these two beams interact in the same detector, scientists have sharpened their ability to rule out potential hiding places for sterile neutrinos. (Samantha Koch/Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory)

But there was some wiggle room in the data, and there were large uncertainties about the detector performance, the model of how neutrinos interact with the liquid that fills the detector, and the production of neutrinos in the beam. In other words, sterile neutrinos might still be “hiding.”

For the new paper just published in Nature, thanks to innovative techniques developed by Brookhaven Lab physicists, the MicroBooNE team expanded their analysis to include a second Fermilab neutrino beam that enabled them to look in more potential hiding places.

This second beamline — the main injector beamline, known as NuMI — was designed to send neutrinos to an experiment 800 miles away. But as the beam travels, it spreads out, just like the beam from a flashlight. Some of the neutrinos in the fanned-out beam passed right through the MicroBooNE detector.

“It is fortuitous that the location of the MicroBooNE detector allowed us to see both neutrino beams,” said Brookhaven physicist Mary Bishai, a member of the MicroBooNE collaboration and a former co-spokesperson for the much larger Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), currently under construction.

First, the NuMI beam adds to the sheer number of rare neutrino interactions within the detector. That increases the statistical power of the analysis. But adding NuMI on top of the booster neutrino beam does much more. Because each beam has a different mix of neutrinos, it allows a certain amount of cross-checking and canceling out of quirks that might show up in one or the other data set but not when the data sets from both beams are combined. In addition, making all the measurements from two different beams in a single detector eliminates all the complexity of comparing results from different experiments with different detector responses, different kinds of neutrino interactions, and a host of other variables.

Still, all that luck would have been essentially worthless if the physicists had not been able to fully understand the characteristics of the neutrinos in the portion of the NuMI beam striking the MicroBooNE detector.

“It’s just a sliver of the beam, about eight degrees off the central axis,” Bishai said. Particle decays within the fanned-out tails of the beam affect the mix of neutrinos in ways that would be irrelevant for a detector right in the line of sight of the beam, she noted.

“We knew we could see those neutrinos, but nobody expected that we could use that information with the precision that we have,” she said.

The Brookhaven team played a central role in modeling the neutrino mix in the off-axis sliver of the NuMI beam. Jo’s team then mathematically combined the results from the two beams.

“Jay’s team drove the analysis techniques to extract more power from the two beams that made this a much more powerful measurement than just adding statistics,” Bishai said.

The off-axis modeling success will likely pay off again at DUNE, where physicists will intentionally move one “near” detector on and off axis to measure different mixes, or spectra, of neutrinos.

“The NuMI beamline is very similar to the DUNE beamline,” Bishai said. “Now that we understand the challenges of modeling the beam off axis, that will help with DUNE.”

The Brookhaven Lab-led analysis team included current Brookhaven Lab postdoctoral fellows Sergey Martynenko and Nitish Nayak. The team also worked in close collaboration with Hanyu Wei and Xiangpan Ji, junior faculty members at Louisiana State University and Nankai University, respectively, who are both former Brookhaven Lab postdocs.

Brookhaven Lab’s contributions to MicroBooNE and DUNE are funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2025-22313 | INT/EXT | Newsroom