Brookhaven Physicist Teams with AI to Solve a Decades-old Physics Maze

The study shows AI's power to help solve highly complex scientific problems — and its role in a new era of research

January 5, 2026

By partnering with artificial intelligence (AI), a researcher at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory has solved a long-standing physics problem and uncovered the mathematical trickery that underlies the generalization of recently discovered, extremely surprising new states of matter. The work exemplifies the paradigm shift that is taking place in research, as scientists learn to see AI as a valuable asset in advancing knowledge and discovery.

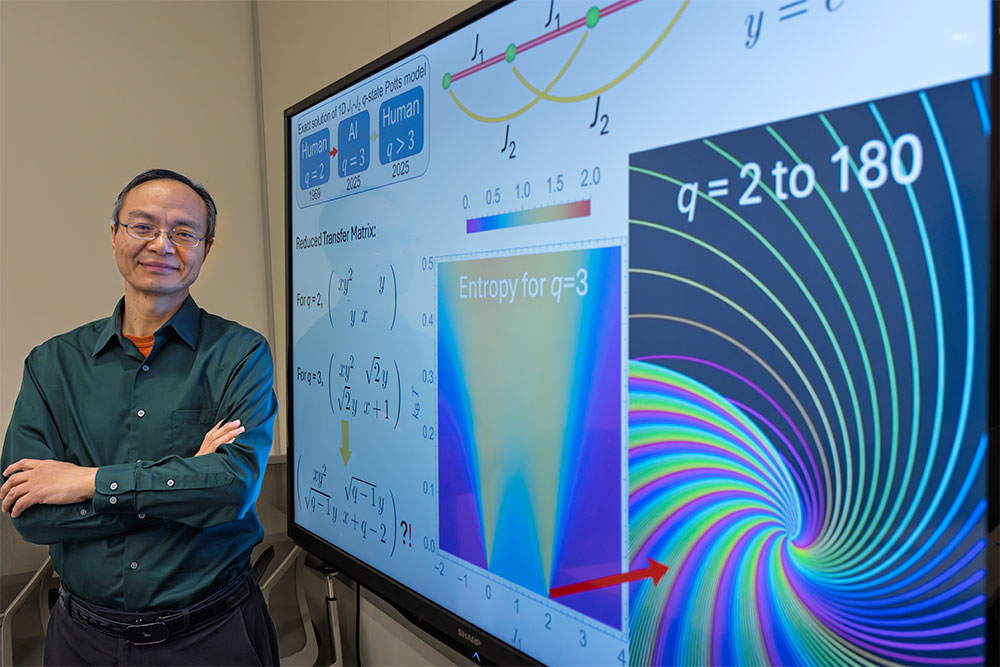

The study, conducted by Brookhaven theoretical physicist Weiguo Yin and described in a recent paper in Physical Review B, is the first paper emerging from the “AI Jam Session” earlier this year, a first-of-its-kind event hosted by DOE and held in cooperation with OpenAI to push the limits of general-purpose large language models applied to science research. The event brought together approximately 1,600 scientists across nine host locations within the DOE national laboratory complex. At Brookhaven, more than 120 scientists challenged and evaluated the capabilities of OpenAI’s latest step-based logical reasoning AImodel built for complex problem solving.

Yin’s AI study focused on a class of advanced materials known as frustrated magnets. In these systems, the electron spins — the tiny magnetic moments carried by each electron — cannot settle on an orientation because competing interactions pull them in different directions. These materials have unique and fascinating properties that could translate to novel applications in the energy and information technology industries.

In the 1960s, physicists reported exact solutions to the simplest case of a one-dimensional (1D) chain of atoms, which permits only two spin orientations: pointing up or pointing down. This is known as the 1D frustrated Ising model. But in many other systems that Yin studies, where the strange rules of quantum physics apply, there can be infinite orientations, making computational modeling very difficult. For example, the Potts model generalizes the Ising model to permit up to infinite spin orientations. It turns out that this 1D frustrated Potts model was just difficult enough to remain unsolved, even for only three spin orientations, and here is where AI comes into play.

Testing the AI

“We know AI is powerful in data analysis and optimization,” Yin said. “But I was skeptical about what it could do in theoretical physics, which is deeply grounded in mathematics. Still, I was willing to give it a try — especially in the classroom-like, synergetic atmosphere of the Jam.”

To gauge the validity of the work of the AI — OpenAI’s then-latest reasoning model, “o3-mini-high" — Yin first fed it a study it could not already know: his recent unpublished paper on a new model for frustrated magnets. He asked the AI to derive the underlying complex mathematics that make that model possible.

To Yin’s surprise, for a critical equation, the AI did not reproduce his exact result but instead produced a mathematically equivalent one — expressed in a form that was far more elegant.

“This is proof that the AI did its own math,” he said. “It was a turning point, and now I was fully convinced that the AI could be my research partner.”

enlarge

enlarge

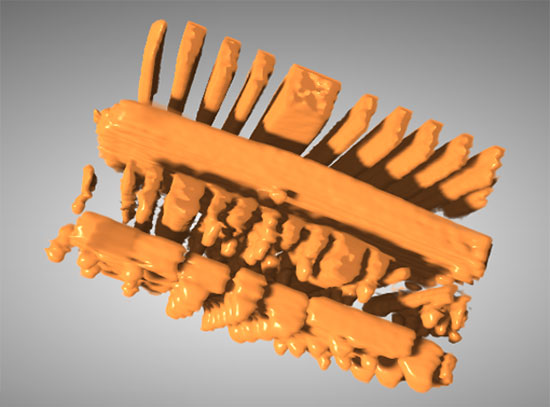

A rendering of the human-AI collaboration: The AI explored at lightning speed, while the human promptly responded to block mistakes. Through this fast iterative interplay, the right path was eventually uncovered. (Lisa Jansson/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Solving the Potts maze: from the specific to the general

The 1D frustrated Potts model can be likened to a square-shaped maze. The challenge arises from the rapid increase in the maze’s size as the maze becomes more complex.

“We used to hesitate at the entrance of even the next simplest maze for three spin orientations, because its corridors look endlessly long,” said Yin. “It was the AI’s lightning speed that made us dare to walk into it.”

Indeed, AI exploited symmetry to simplify the maze and solved the case for three spin orientations — in only one day.

Like any colleague, the AI was not perfect. It did often make mistakes during the prompts, exactly like what happens when one navigates a maze.

“It is up to us to spot its errors quickly,” Yin said. “By effectively blocking AI’s wrong moves, we help it to find the right ones — even when we have no idea of the right direction ourselves.”

Now having the results for two simplest cases in hand, Yin identified a pattern and worked out a rigorous proof for an arbitrary number of spin orientations. The result was a remarkably simple solution that extended all the way to infinite possible spin orientations. This 1D frustrated Potts model — once a daunting, fundamental problem in statistical mechanics and materials science — was thus fully solved.

Unveiling the unknowns

Yin’s general solution revealed a rich phase diagram that could explain how atomic layers stack in materials that have applications in traditional computing, electronics, and next-generation quantum and photonic devices. The solution also uncovered several unexpected novel results, including an exact mapping of this frustrated Potts model onto a simpler Potts model in an effective external magnetic field. The existence of infinitely many exact mappings raises the general question of to what extent the frustration induced by an external magnetic field corresponds to the geometrical frustration arising spontaneously from competing spin interactions. These unknowns can guide not only fundamental research but also material designs. These insights have already been used in Yin’s recent work with experimental groups at Brookhaven.

“Interacting with AI is like engaging with the collective knowledge of the world,” said Yin.

He noted that he appreciated the conversational aspect of the AI reasoning system because interaction felt not just logical but dialogical.

“Like in a Socrates-style dialogue, both people are trying to find the ‘magic’ in the other person’s argument and then identify something new that inspires them to solve a problem,” he said. “The solution, or even the problem, emerges from the conversation.”

As a next step, Yin will use this AI-aided approach to model systems with more complex atomic and electronic structures, such as strongly correlated electronic systems with intertwined charge, spin, orbital, and lattice characteristics that can host exotic phenomena, including high-temperature superconductivity and quantum entanglement vital to energy and information technology applications.

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22742 | INT/EXT | Newsroom