Fundamental Physics Lessons in Sub-Saharan Africa

Brookhaven Lab Supports Third African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications

September 30, 2014

enlarge

enlarge

2014 African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications participants. Brookhaven Lab physicist and organizing committee member Ketevi Assamagan is in the back row, sixth from the left. Brookhaven Lab was among nearly 50 supporting institutions from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Nearly four thousand miles east of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven Lab, 56 students gathered in the sub-Saharan nation of Senegal to talk physics at the 2014 African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications last month. There, 36 scientists from around the world introduced the students to the theories, experiments, and technologies that power major physics collaborations like those at RHIC and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN in Europe, where scientists are exploring the universe’s tiniest building blocks of matter.

“We show the students that the mathematical and scientific principles we teach are important for applications ranging from medical procedures and devices to nanotechnology and energy. And we hope these aspiring young physicists continue in the field, and become collaborators or users at Brookhaven and the other national labs."

— Ketevi Assamagan, Brookhaven Lab physicist & organizing committee member

This third biennial event was held from Aug. 3 to Aug. 23 at the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal's capital city, located on the westernmost peninsula along Africa’s Atlantic coast.

Brookhaven Lab was among nearly 50 institutions from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Africa—including DOE's Fermilab, Jefferson, Sandia, SLAC national laboratories; the National Science Foundation; and CERN—that supported the school by helping pay for the program, organizers, and students.

With high temperatures and humidity levels outside, the 18 women and 38 men undergraduate, graduate, and Ph.D. students selected from 328 applicants enjoyed air-conditioned classrooms inside while participating in lectures and interactive exercises from 9 a.m. to as late as 6:30 p.m. five days a week. During the first week, they learned about nuclear and particle physics theory, and completed a primer on the Linux computer operating system, which scientists often use for experiments, data analysis, and simulations. Participants learned about experimental physics in the second week, focusing on detector designs and construction, and they wrapped up the last week with discussions about physics and its relevance in applications for impact in medical, solar energy, and nanotechnology.

Students and lecturers as well as delegates from conference supporters CERN and the International Telecommunication Union also met with members of the local and central Senegalese governments during the three-week session to discuss plans for education in Africa, and to identify African nations' common issues and opportunities for cooperation.

enlarge

enlarge

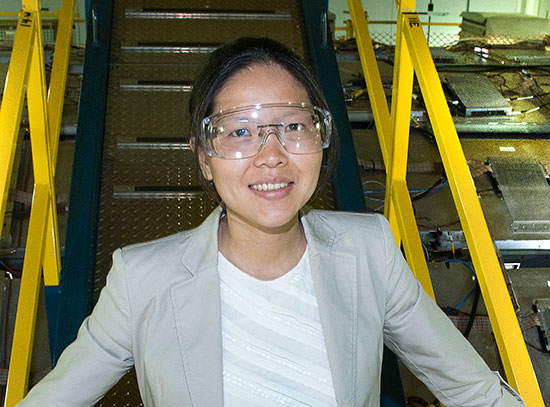

Ketevi Assamagan, a Brookhaven Lab physicist and organizing committee member, during the 2014 African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications

"These are very smart students with great enthusiasm and potential, so we're glad to give them this opportunity and inspire them to see how fundamental physics can ultimately benefit the human race," said organizing committee member and Brookhaven Lab physicist Ketevi Assamagan.

In addition to Assamagan, members of the school's organizing committee included Bobby Acharya of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics and King’s College London; Christine Darve of the European Spallation Source in Sweden; John Ellis, also of King’s College London; Steve Muanza of the National Centre for Scientific Research National Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics in France; and Rudiger Voss of CERN. Brookhaven Lab's Associate Laboratory Director for Nuclear & Particle Physics Berndt Mueller and Physics Department Deputy Chair Howard Gordon are members of the school's international advisory committee.

Assamagan added, "We had to make some last-minute changes to the curriculum this year, when some lecturers cancelled because of Ebola outbreaks in other African countries. We kept monitoring World Health Organization updates before and during the school, and since Senegal was not really affected at time, the school could go on. And I'm glad it did, because it was a great experience for the students and the instructors."

Organizers also planned social activities for weekends to foster networking among participants, who were invited to a banquet, and excursions to Bandia Nature Reserve—which is home to giraffes, rhinoceroses, zebras, buffaloes, and more—and Goree Island, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization World Heritage site.

Few African Scientists in International Collaborations

enlarge

enlarge

Organizing committee member Bobby Acharya of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics and King's College London with students Ibrahim Omer Abdallah, Abdul Rahim Umar, and Jaouad El Falaki

“In general, we see few scientists from Africa participating in physics experiments and programs at major labs around the world. This program gives students from Africa the opportunity network with members of the international physics community and each other, so they can be inspired, well informed, and well connected, which will help them succeed wherever they go," Assamagan said.

“We show the students that the mathematical and scientific principles we teach are important for applications ranging from medical procedures and devices to nanotechnology and energy,” Assamagan added. "And we hope these aspiring young physicists continue in the field, and become collaborators or users at Brookhaven and the other national labs."

Assamagan himself was born in the African country of Gabon and raised in Togo. He earned a Ph.D. in nuclear and particle physics and is a physicist at Brookhaven Lab and member of the U.S. ATLAS collaboration at the LHC. In the hunt for the Higgs Boson, the particle from the Standard Model of Physics—the theory that identifies all known subatomic particles and explains how they interact—Assamagan worked with the ATLAS detector’s muon spectrometer to measure paths and momenta of charged particles called muons that emerge from collisions and are about 200 times heavier than electrons. He also works with ATLAS analysis software, led the ATLAS Higgs Physics Working Group for two years, and is currently involved in various analyses in search of possible new physics discoveries.

Fostering Scientific Literacy & Future Scientists

“The African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications is possible because our sponsors, including Brookhaven, are committed to promoting scientific literacy and helping inspire the next generation of scientists who will work to answer serious scientific questions,” said Assamagan, noting that Brookhaven’s Diversity Office was particularly supportive of the program.

It’s early to plan for the next school scheduled for 2016, but Assamagan and his five fellow members of the international organizing committee will begin making preparations later this year. In the meantime, they stay in touch with nearly all 171 students who have completed the program—56 in 2014, 50 in 2012, and 65 in 2010— emailing participants updates about opportunities such as internships and scholarships. Participants stay connected via Facebook too.

“We may be separated by land and a big ocean, but this a great time in history to collaborate!” Assamagan said.

Watch a video about the 2014 African School of Fundamental Physics and its Applications online.

2014-5187 | INT/EXT | Newsroom