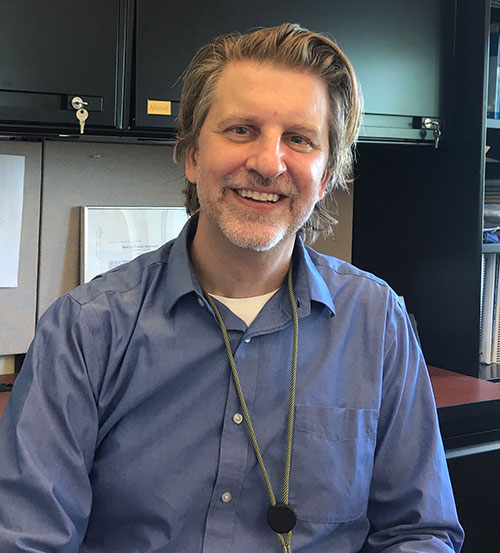

A Message from Chuck Black

insights from the CFN Director

September 15, 2021

Chuck Black

The Olympic Games took place this past summer in Tokyo, and like some of you, I’m sure, I watched as much of them as I could. I have loved the Olympics ever since I was a kid. Watching amazing athletes from all over the world represent their countries and compete at the absolute highest levels is, for me, a truly special occasion—one not to be missed.

At the Olympics, the stakes are so high and the pressure so intense, with many talented athletes spending their lifetimes preparing for this single sporting event. The two weeks of competition provide a rare opportunity for all of us to witness the best of what human beings can do. As I have gotten older, I have increasingly enjoyed observing excellence, in all its different forms. It’s enthralling to see humans perform with excellence—whether in sports, in the case of the Olympics, or in science, the arts, or any other vocation. The beauty of these kinds of performances can inspire so much respect and admiration that it brings a lump to your throat. Along with the heroic victories, the Olympics also generate heartbreaking disappointments and inspiring moments of resilience. The tragic events are poignant and can be difficult to watch, but they remind me that sometimes in life it’s important to take the risk of committing to something absolutely. As the American middle-distance runner Isaiah Jewett told a reporter after his race, “If you’re giving everything you have, you don’t have anything to regret.”

Watching Olympic athletes striving to achieve their ultimate professional goals made me think about CFN staff and users, who are also working to advance our field of nanoscience in ways that make a difference. Let me share three short stories from this year’s Olympics and why I will remember them:

-

In our household, we love the swimmer Katy Ledecky, and if you have ever seen Ledecky swim and heard her speak, I bet you do, too. She is a phenomenal athlete, a world record holder, and one of the best swimmers the world has ever seen. In this Olympics, Ledecky competed in four different events. One night, the schedule was organized such that Ledecky would swim the finals of two different races spaced just an hour or so apart—a very difficult challenge. In the first final, Ledecky swam to fifth place, which I doubt is the result she was expecting.

All of us have had similar experiences, where we feel intense disappointment after striving and failing to achieve a personal goal.Few will ever experience the weight of that disappointment in front of the world, with the expectations of being a world champion representing our country resting on our performance. After her fifth-place finish and with just an hour between races, Ledecky collected herself for the second final. In that race, Ledecky swam and won the gold medal, jumping and slapping the water in joy, and crying in happiness when she realized what she had done. Witnessing the totality of her performance—her disappointment, followed by her resilience, and ultimately her triumph and joy—brought me to tears.

Ledecky is 24 years old, and this summer marked her third time competing in the Olympics. When her races finished, Ledecky was asked, “Do you think this is your last Olympics, forever?” I will remember her response, which was first to look at the reporter without speaking. It seemed for a moment as if she couldn’t understand the question. After the short pause, Ledecky answered, “Absolutely not. I love swimming so much. I'll definitely be back for the next Olympics in 2024, and hopefully for 2028, too." In that brief exchange, Ledecky reminded me that one of life’s most satisfying aspects is finding your passion—and committing wholly to it.

-

I have a special respect for runners. I am astonished by the explosive power and raw speed of sprinters, the strength and mental will of longer-distance runners, and the unreal combination of speed, strength, and endurance of middle-distance runners. This year, the semifinal of the men’s 800-meter event featured Isaiah Jewett. Jewett, only 24 years old and a college student, had won the U.S. Olympic trials earlier this summer and arrived at the Olympics with his performance peaking at just the right time. He seemed poised to contend for a medal.

In the semifinal, Jewett was running well and in good position to qualify for the finals. Upon approaching the final turn, however, disaster struck. Jewett and another runner, Nijel Amos, were running very close together, and tangled their legs. In an instant, the two fell crashing to the track. The rest sped away toward the finish while Jewett and Amos lay crumpled on the ground. In a split second, all of Jewett’s plans and aspirations for this Olympics were gone.

And yet, as the world watched, Jewett got to his knee, looked over at Amos, and extended his arm so that the two could pull each other to their feet. They traded private words, perhaps even in different languages, and walked the last 100 meters arm-in-arm to the finish.

When talking later about the race, Jewett described his feelings upon falling to the track: “As I was falling, at first I felt like this wasn’t really me. That this was happening to somebody else. I could feel myself start to get down.”

Jewett continued: “But when I was on the ground, I looked over at the other runner and saw the defeat on his face. I didn't want to hurt, and I didn't want him to hurt. I wanted to do something that was good, to do something that was right. So, I said, ‘Let’s get up and finish this race.’”

I was struck my Jewett’s magnanimity, especially after learning his thoughts just as the fall happened. Placed in a similar circumstance, I’m not sure I could put aside my hurt and disappointment so quickly. In that moment, Jewett reminded me of the balance we continually seek in our lives, between satisfying our personal ambitions and helping others in kinship.

“If you are giving everything you have, you don’t have anything to regret,” said Jewett. “Things might turn out differently than you want, but that’s life.”

-

A couple of days before seeing Jewett run his race, I watched a preliminary round of the same event—the men’s 800-meter run. Very close to the beginning of that race, I saw a runner urgently competing to get to the front of the group. Here too, as happened several days later in Jewett’s race, there was a tangle of legs and bodies because so many people were running so close together, and this runner fell to the track. The pack of others quickly moved on, leaving the fallen runner behind. This time, however, the fallen runner got back up, and, although he was alone and hopelessly lagging the others, he ran on.

The race finished, with the winner breaking the tape and others with sufficiently fast times also qualifying to continue to the next round. After everyone else had finished, the runner who had fallen crossed the line, crying. Once through the finish, the runner lay down on the track and continued crying, disconsolate. Before cutting away to show another event, the television announcer said the runner James Chiengjiek was a member of the Refugee Olympic Team—athletes without a home country. I later learned Chiengjiek was born in South Sudan but fled his home country after some of his family members were killed in civil war. Chiengjiek settled in a refugee camp in Kenya, where he later found a passion for running.

It’s difficult for me to take concrete lessons from witnessing this heartbreaking event. I have such respect for Chiengjiek’s resilience as a human being. After learning his life story, I understand a bit why Chiengjiek got back to his feet and continued racing after falling to the track, even though he was hurt, deeply disappointed, and far behind. Chiengjiek has persevered in circumstances far more challenging than a sporting event can ever be. In a larger sense, I am astounded by the human spirit; a person who fled their home country in extreme distress can still feel called by their passion and compelled to commit to it so completely. And I am troubled by a world in which so many people are without even their home country to be a member of.

If I had to take a lesson from these Olympic stories, it is this:

I feel so fortunate to live in the United States, which for all its challenges will always be the place I love the most. And, regardless of our home countries, those of us connected to the CFN as staff members, users, or friends are fortunate to be participants in a society that values science and knowledge so much that we have created a system of U.S. National Laboratories, staffed them with talented scientists, and charged us with a mission to carry out transformative research to create a better future for us all.

In exchange for this tremendous, good fortune, I believe we owe the world our best scientific efforts. I talk often about the importance of the CFN mission, which is to understand the nanoscience of materials so that we can improve our world. After experiencing the Olympics this summer, I felt compelled to ask myself some hard questions. You may consider asking yourself the same ones:

- Am I truly giving my best effort? Am I fully committed and giving everything I have, even knowing the risk of failure?

- Am I resilient after setbacks? Am I getting back up after being knocked down?

- Am I truly doing important work, of the type that can transform the future and make the world better?

The world needs our best efforts, now more than ever. Let’s continue to work together to make a difference.

— Charles Black

CFN Director

2021-19128 | INT/EXT | Newsroom