Staying Cool: Saharan Silver Ants

Researchers first to show that Saharan silver ants can control electromagnetic waves over an extremely broad range of the electromagnetic spectrum—findings may lead to biologically inspired coatings for passive radiative cooling of objects

June 18, 2015

The following press release was first issued by Columbia Engineering. Some of the research was carried out at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory. See sidebar and accompanying feature story for more info on Brookhaven Lab's role.

Columbia Engineering media contact: Holly Evarts, Director of Strategic Communications and Media Relations, 212-854-3206 (o), 347-453-7408 (c), holly.evarts@columbia.edu

enlarge

enlarge

Silver ant optical macro with two panels:Left: Sahara silver ants forage in the midday sun and look like droplets of mercury rolling on the desert surface. Right: The silvery appearance is created by a dense array of uniquely shaped hairs. Credit: Norman Nan Shi and Nanfang Yu, Columbia Engineering

New York, NY—June 18, 2015—Nanfang Yu, assistant professor of applied physics at Columbia Engineering, and colleagues from the University of Zürich and the University of Washington, have discovered two key strategies that enable Saharan silver ants to stay cool in one of the hottest terrestrial environments on Earth. Yu's team is the first to demonstrate that the ants use a coat of uniquely shaped hairs to control electromagnetic waves over an extremely broad range from the solar spectrum (visible and near-infrared) to the thermal radiation spectrum (mid-infrared), and that different physical mechanisms are used in different spectral bands to realize the same biological function of reducing body temperature. Their research, "Saharan silver ants keep cool by combining enhanced optical reflection and radiative heat dissipation," is published June 18 in Science magazine.

"This is a telling example of how evolution has triggered the adaptation of physical attributes to accomplish a physiological task and ensure survival, in this case to prevent Sahara silver ants from getting overheated," Yu says. "While there have been many studies of the physical optics of living systems in the ultraviolet and visible range of the spectrum, our understanding of the role of infrared light in their lives is much less advanced. Our study shows that light invisible to the human eye does not necessarily mean that it does not play a crucial role for living organisms."

The project was initially triggered by wondering whether the ants' conspicuous silvery coat was important in keeping them cool in blistering heat. Yu's team found that the answer to this question was much broader once they realized the important role of infrared light. Their discovery that that there is a biological solution to a thermoregulatory problem could lead to the development of novel flat optical components that exhibit optimal cooling properties.

"Such biologically inspired cooling surfaces will have high reflectivity in the solar spectrum and high radiative efficiency in the thermal radiation spectrum," Yu explains. "So this may generate useful applications such as a cooling surface for vehicles, buildings, instruments, and even clothing."

Saharan silver ants (Cataglyphis bombycina) forage in the Saharan Desert in the full midday sun when surface temperatures reach up to 70°C (158°F), and they must keep their body temperature below their critical thermal maximum of 53.6°C (128.48°F) most of the time. In their wide-ranging foraging journeys, the ants search for corpses of insects and other arthropods that have succumbed to the thermally harsh desert conditions, which they are able to endure more successfully. Being most active during the hottest moment of the day also allows these ants to avoid predatory desert lizards. Researchers have long wondered how these tiny insects (about 10 mm, or 3/8" long) can survive under such thermally extreme and stressful conditions.

enlarge

enlarge

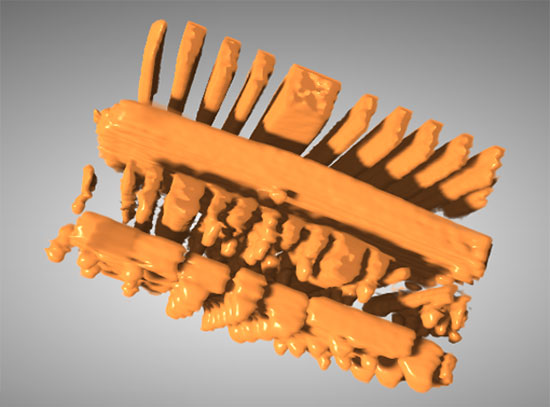

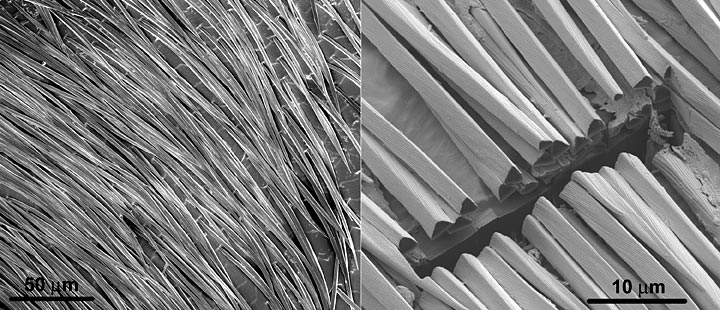

Scanning electron micrographs of the hair coating on the silver ant. The hairs grow parallel to the skin and are separated from the skin by a small air gap. The hairs have triangular cross-sections with two corrugated top facets and a flat bottom facet facing the ant's body. Credit: Norman Nan Shi and Nanfang Yu, Columbia Engineering

Using electron microscopy and ion beam milling, Yu's group discovered that the ants are covered on the top and sides of their bodies with a coating of uniquely shaped hairs with triangular cross-sections that keep them cool in two ways. These hairs are highly reflective under the visible and near-infrared light, i.e., in the region of maximal solar radiation (the ants run at a speed of up to 0.7 meters per second and look like droplets of mercury on the desert surface). The hairs are also highly emissive in the mid-infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, where they serve as an antireflection layer that enhances the ants' ability to offload excess heat via thermal radiation, which is emitted from the hot body of the ants to the cold sky. This passive cooling effect works under the full sun whenever the insects are exposed to the clear sky.

"To appreciate the effect of thermal radiation, think of the chilly feeling when you get out of bed in the morning," says Yu. "Half of the energy loss at that moment is due to thermal radiation since your skin temperature is temporarily much higher than that of the surrounding environment."

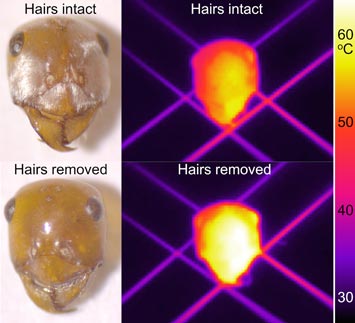

The researchers found that the enhanced reflectivity in the solar spectrum and enhanced thermal radiative efficiency have comparable contributions to reducing the body temperature of silver ants by 5 to 10 degrees compared to if the ants were without the hair cover. "The fact that these silver ants can manipulate electromagnetic waves over such a broad range of spectrum shows us just how complex the function of these seemingly simple biological organs of an insect can be," observes Norman Nan Shi, lead author of the study and PhD student who works with Yu at Columbia Engineering.

enlarge

enlarge

Thermodynamic figure comparing the temperature of ant head with and without hairs. The hair coating helps reduce body temperature substantially (via enhanced reflection of solar radiation and enhanced thermal radiation). Credit: Norman Nan Shi and Nanfang Yu, Columbia Engineering

Yu and Shi collaborated on the project with Rüdiger Wehner, professor at the Brain Research Institute, University of Zürich, Switzerland, and Gary Bernard, electrical engineering professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, who are renowned experts in the study of insect physiology and ecology. The Columbia Engineering team designed and conducted all experimental work, including optical and infrared microscopy and spectroscopy experiments, thermodynamic experiments, and computer simulation and modeling. They are currently working on adapting the engineering lessons learned from the study of Saharan silver ants to create flat optical components, or "metasurfaces," that consist of a planar array of nanophotonic elements and provide designer optical and thermal radiative properties.

Yu and his team plan next to extend their research to other animals and organisms living in extreme environments, trying to learn the strategies these creatures have developed to cope with harsh environmental conditions.

"Animals have evolved diverse strategies to perceive and utilize electromagnetic waves: deep sea fish have eyes that enable them to maneuver and prey in dark waters, butterflies create colors from nanostructures in their wings, honey bees can see and respond to ultraviolet signals, and fireflies use flash communication systems," Yu adds. "Organs evolved for perceiving or controlling electromagnetic waves often surpass analogous man-made devices in both sophistication and efficiency. Understanding and harnessing natural design concepts deepens our knowledge of complex biological systems and inspires ideas for creating novel technologies."

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation under the Electronics, Photonics, and Magnetic Devices program (ECCS-1307948) and Physics of Living Systems program (PHY-1411445), and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) Multidisciplinary Research Program of the University Research Initiative (MURI) program (FA9550-14-1-0389).

Research was also carried out in part at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, Brookhaven National Laboratory.

2015-11737 | INT/EXT | Newsroom