New Evidence for Small, Short-Lived Drops of Early Universe Quark-Gluon Plasma?

Scientists reveal correlated flow of particles emerging from even the lowest-energy, small-scale collisions at Big-Bang particle collider

September 18, 2017

enlarge

enlarge

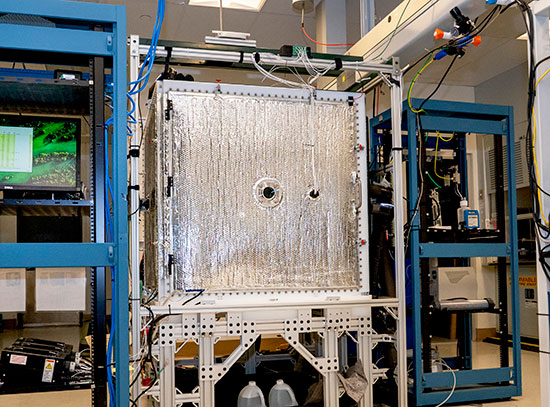

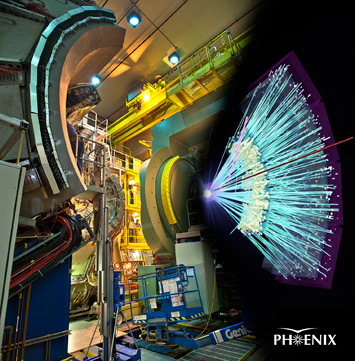

The PHENIX detector at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) with a superimposed image of reconstructed particle tracks picked up by the detector.

Scientists built RHIC, in large part, to create this “quark-gluon plasma” (QGP) so they could study its properties and learn how Nature’s strongest force brings quarks and gluons together to form the protons, neutrons, and atoms that make up the visible universe today. But they initially expected to see signs of QGP only in highly energetic collisions of two heavy ions such as gold. The new findings—correlations in the way particles emerge from the collisions that are consistent with what physicists have observed in the more energetic large-ion collisions—add to a growing body of evidence from RHIC and Europe’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that QGP may be created in smaller systems as well.

The PHENIX collaboration has submitted the findings in two separate papers to the journals Physical Review Letters and Physical Review C, and will present these results at a meeting in Krakow, Poland this week.

“These are the first papers that come out of the 2016 deuteron-gold collisions, and this is one indication that we are probably creating QGP in small systems,” said Julia Velkovska, a deputy spokesperson for PHENIX from Vanderbilt University. “But there are other things that we have seen in the larger systems that we have yet to investigate in this new data. We’ll be looking for other evidence of QGP in the small systems using different ways to study the properties of the system we are creating,” she said.

Collective flow

One of the earliest signs that RHIC’s collisions of two gold ions were creating QGP came in the form of “collective flow” of particles. More particles emerged from the “equator” of two semi-overlapping colliding ions than perpendicular to the collision direction. This elliptical flow pattern, scientists believe, is caused by interactions of the particles with the nearly “perfect”—meaning free-flowing—liquid-like QGP created in the collisions. Since then, collisions of smaller particles with heavy ions have resulted in similar flow patterns at both RHIC and the LHC, albeit on a smaller scale. There has also been evidence that flow patterns have a strong relationship with the geometrical shape of the projectile particle that is colliding with the larger nucleus.

“With these results in hand, we wanted to try smaller and smaller systems at different energies,” Velkovska said. “If you change the energy, you can change the time that the system stays in the liquid phase, and maybe make it disappear.”

In other words, they wanted to see if they could turn the creation of QGP off.

We are trying to understand how the perfect-fluid behavior emerges and evolves.

— PHENIX deputy spokesperson Julia Velkovska, Vanderbilt University

“After so many years we have learned that when QGP is created in the collisions we know how to recognize it, but that doesn’t mean we really understand how it works,” Velkovska said. “We are trying to understand how the perfect-fluid behavior emerges and evolves. What we are doing now—going down in energy, changing the size—is an effort to learn how this behavior arises in different conditions. RHIC is the only collider in the world that allows such a range of studies over different collision energies with different colliding particle species.”

Turning down the energy

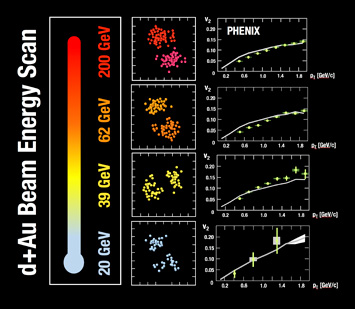

Over a period of about five weeks in 2016, the PHENIX team explored collisions of deuterons (made of one proton and one neutron) with gold ions at four different energies (200, 62.4, 39, and 19.6 billion electron volts, or GeV).

“Thanks to the versatility of RHIC and the ability of the staff in Brookhaven’s Collider-Accelerator Department to quickly switch and tune the machine for different collision energies, PHENIX was able to record more than 1.5 billion collisions in this short period of time,” Velkovska said.

enlarge

enlarge

For each collision energy in the beam energy scan, the central panel shows an early-time snapshot of the coordinates of quarks emerging from a deuteron-gold (d-Au) collision as simulated in a transport-model theory calculation. The right panel shows the elliptic flow of the final-state hadrons as measured by PHENIX (closed points), along with the prediction from the theory (solid curve).

“Using a deuteron projectile produces a highly elliptical shape, and we observed a persistence of that initial geometry in the particles we detect, even at low energy,” McGlinchey said. Such shape persistence could be caused by interaction with a QGP created in these collisions. “This result is not sufficient evidence to declare that QGP exists, but it is a piece of mounting evidence for it,” he said.

Ron Belmont, a PHENIX collaborator from the University of Colorado, led an analysis of how the flow patterns of multiple particles (two and four particles at each energy and six at the highest energy) were correlated. Those results were submitted to PRL.

“We found a very similar pattern in both two- and four-particle correlations for all the different energies, and in six-particle correlations at the highest energy as well,” Belmont said.

“Both results are consistent that particle flow is observed down to lowest energy. So the two papers work together to paint a nice picture,” he added.

There are other possible explanations for the findings, including the postulated existence of another form of matter known as color glass condensate that is thought to be dominated by the presence of gluons within the heart of all visible matter.

“To distinguish color glass condensate from QGP, we need more detailed theoretical descriptions of what these things look like,” Belmont said.

Velkovska noted that many new students have been recruited to continue the analysis of existing data from the PHENIX experiment, which stopped taking data after the 2016 run to make way for a revamped detector known as sPHENIX.

“There is a lot more to come from PHENIX,” she said.

Research at RHIC is funded by the DOE Office of Science (NP) and by the agencies and institutions associated with PHENIX listed here.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

2017-12493 | INT/EXT | Newsroom