AI Streamlines Deluge of Data from Particle Collisions

Scientists' custom algorithm compresses data and speeds processing to capture more collisions for discoveries

February 2, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

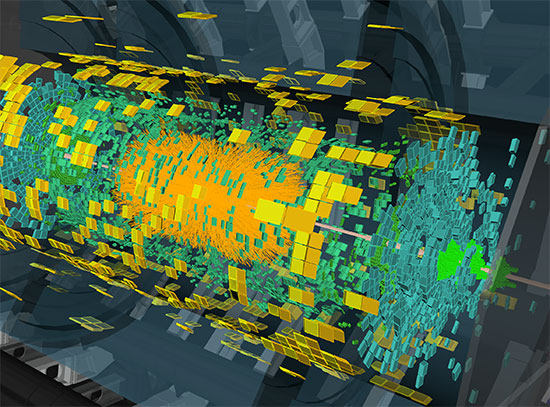

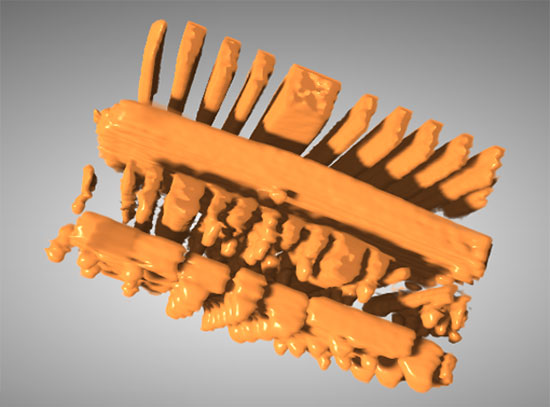

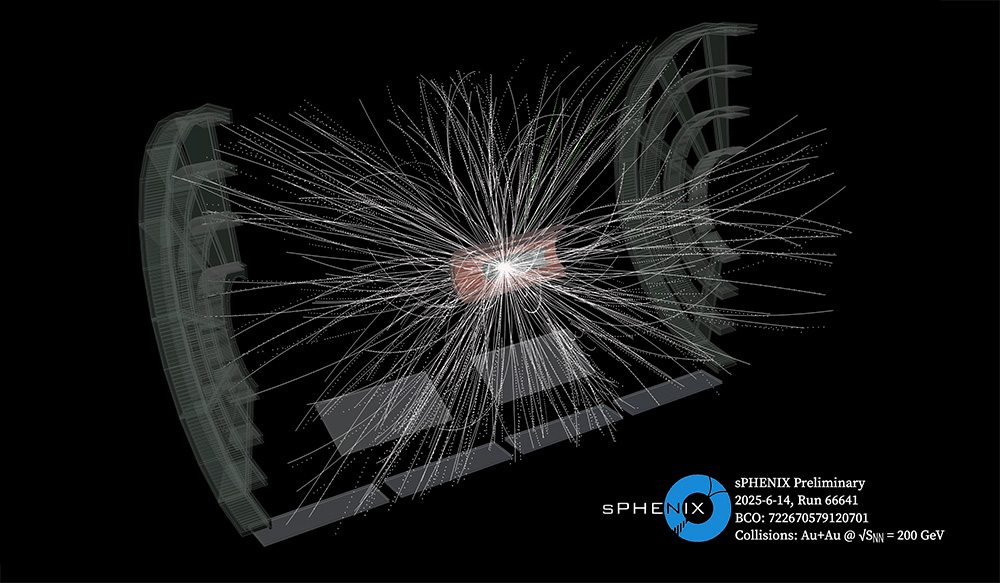

Particle collisions produce many tracks inside the sPHENIX time projection chamber, but most of the volume of the house-sized detector is empty. Brookhaven scientists have developed a new algorithm for compressing such "sparse" data so the detector can record many more collision events that could lead to discoveries. (sPHENIX Collaboration)

UPTON, N.Y. — Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have developed a novel artificial intelligence (AI)-based method to dramatically tame the flood of data generated by particle detectors at modern accelerators. The new custom-built algorithm uses a neural network to intelligently compress collision data, adapting automatically to the density or “sparsity” of the signals it receives.

As described in a paper just published in the journal Patterns, the scientists used simulated data from sPHENIX, a particle detector at Brookhaven Lab’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), to demonstrate the algorithm’s potential to handle trillions of bits of detector data per second while preserving the fine details physicists need to explore the building blocks of matter. The algorithm will help physicists gear up for a new era of streaming data acquisition, where every collision is recorded without pre-selecting which ones might be of interest. This will vastly expand the potential for more accurate measurements and unanticipated discoveries.

“Our goal is to improve the scientific capability of particle detectors like sPHENIX at RHIC and detectors at future colliders, including the upcoming Electron-Ion Collider (EIC),” said Jin Huang, the principal investigator for this project. The EIC is a state-of-the-art nuclear physics research facility to be built at Brookhaven Lab after RHIC completes its scientific mission later this year.

Taming the data deluge

RHIC is a DOE Office of Science user facility that accelerates beams of particles ranging from protons to heavy atomic nuclei, such as gold, and steers them into head-on collisions so scientists can explore the building blocks of matter and the forces that hold them together. Collisions occur thousands of times per second, each potentially creating thousands of new subatomic particles that streak through detectors like the time projection chamber at sPHENIX.

Acting like a 3D digital camera, the time projection chamber records the particles’ trajectories in a gas-filled chamber using nearly 160,000 electronic channels. The electronic sensors that make up the detector produce a data flow of trillions of data points — known as voxels in such 3D images — per second.

enlarge

enlarge

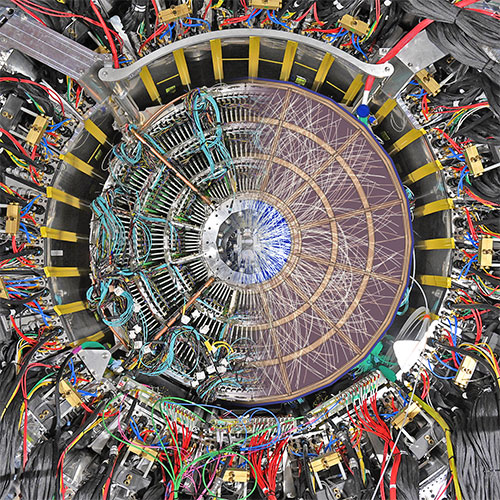

This split-screen end view of the sPHENIX detector shows detector components and superimposed particle tracks. (Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory and the sPHENIX Collaboration).

“Right now, RHIC is producing more collision events than we can record in our experiments,” Huang said. “To maximize the physics output from the facility, we need a reliable and innovative way to pack more information into each byte of data recorded so we can eliminate the need for an event selection bias and record more and more collision events.”

The most promising approach is data compression on the fly — finding shorthand ways to collectively describe key features of the data instead of including all the repeating details of every data point. Successful shorthand encoding would allow an accurate picture to be reconstructed once the data is decompressed while minimizing the loss of crucial information.

“As an example, instead of recording every single pixel of a red square, it would be more efficient to describe a square with a particular side length and red color. AI is very good finding such high-level abstraction of patterns,” said Yihui (Ray) Ren, a member of Brookhaven Lab’s Computing and Data Sciences team who led the AI aspects of this project.

Of course, the data produced in particle collisions is considerably more complex. And the data is actually quite sparse. This may sound like a contradiction, given the scale of the signals described above. But even with the number of particles produced during energetic smashups inside the house-sized detector, their tracks take up very little space in the time projection chamber; most of the vast number of voxels recorded for each collision are empty.

“Traditional data compression tools designed for weather models or fluid simulations, which work well for data that is more continuous, don’t work well on such sparse data,” said Ren. “So, we have to innovate and design our own approach.”

Smarter data compression

The new algorithm uses an AI architecture that processes only the non-empty parts of the data. It was developed by a Brookhaven-led team, including members of sPHENIX and the Lab’s Computing and Data Sciences directorate, along with collaborators from Texas A&M University, Columbia University, UCLA, and Stony Brook University.

“Our algorithm can zoom in on the meaningful parts of the picture — the few voxels filled by particle tracks — and do computation only on these values,” said Yi Huang, a computational scientist at Brookhaven Lab and the lead author on the paper. Contrast this with a conventional algorithm that would run computations on even the empty background voxels, which can often impede performance.

“In this way, sparsity becomes an advantage for us,” she said. “The fewer voxels with meaningful values, the less computation our algorithm needs to do, resulting in faster data processing.”

In addition, as in the red square example, the algorithm scans through the data to identify repetitive features or key points, and it develops shorthand to describe those features collectively. In parallel, a decompressor component of the algorithm tries to use that description, or code, to reconstruct the data, and it compares the reconstructed data with the original input, prior to compression.

After training over a large dataset, the algorithm learns the best ways to maximize data compression while keeping information loss as low as possible to avoid sacrificing key data features essential for discoveries.

enlarge

enlarge

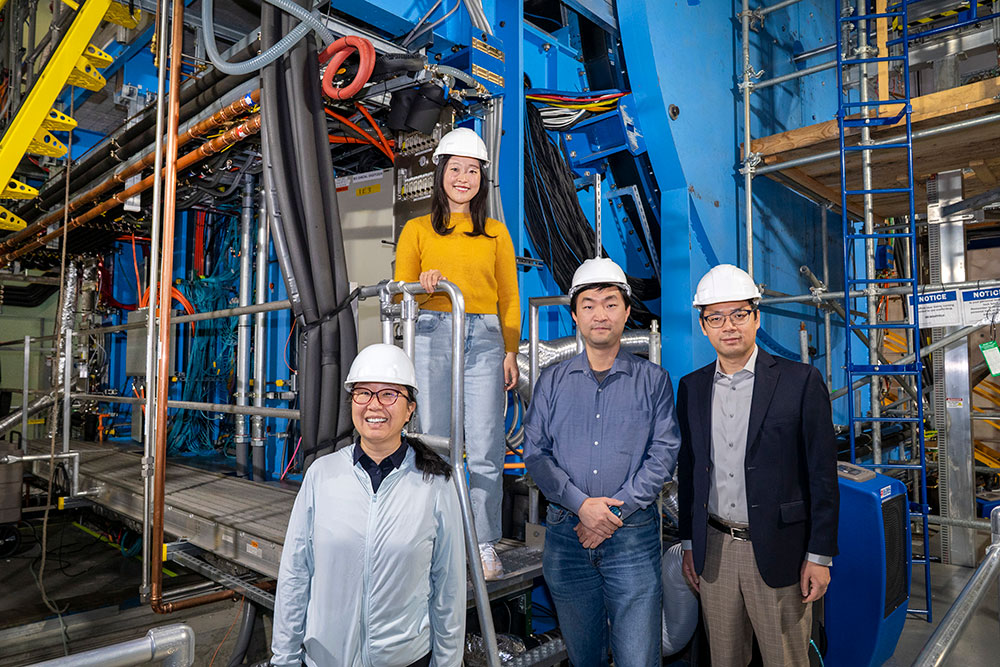

Yi Huang, Yeonju Go, Jin Huang, and Yihui (Ray) Ren stand at the sPHENIX detector of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. They are part of a team that developed an AI algorithm to compress sPHENIX data so more events can be recorded for future discoveries. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

More compact, faster, and more accurate

So far, the team has tested the algorithm on simulated data generated for sPHENIX’s time projection chamber. In those tests, compared to previous models, the new algorithm achieved: a model size that is more than 100 times more compact — all while maintaining high processing speed as the data become sparser; 75% less error in reconstructing raw data; and 10% higher compression ratio, meaning 10% more collision data can be saved.

This performance makes the algorithm especially promising for streaming data acquisition systems, which continuously record all collisions instead of using “triggers” to capture only events that meet certain predetermined criteria.

“Triggers are an effective way to narrow the data you collect if you already know what kind of event you are looking for,” Huang said. “But if you want to be able to minimize selection bias or to make discoveries about unknown physics, it’s better to have all the data preserved so you can analyze it in many different ways — even many years in the future.”

sPHENIX’s particle-tracking system was designed to use streaming readout, and the ePIC detector for the EIC is expected to use this approach as well.

To move beyond simulations to handling real detector signals, the team will need to expand their work and demonstrate that the algorithm can manage electronic noise and other signal-masking complexities. They are also exploring optimizations that could enable deployment on innovative AI chips that are much faster and more energy efficient than the processing units currently used for many computing applications

“Our ultimate goal is to integrate intelligent data compression directly into the detector readout chain to better explore the frontier of physics with a faster and smarter data pipeline," said Huang.

The custom AI approach could also be useful in other fields involving sparse data, for example, in event-based cameras used for security applications.

This research was supported by Brookhaven’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program and carried out in collaboration with the sPHENIX Collaboration at RHIC. The project builds on earlier work by the same team listed in the related links. RHIC operations are funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22693 | INT/EXT | Newsroom