ATLAS Confirms Collective Nature of Quark Soup's Radial Expansion

Systematic analysis of particles "pushed" outward from collisions offers new insight into the fluid nature and viscosity of the quark-gluon plasma

January 22, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

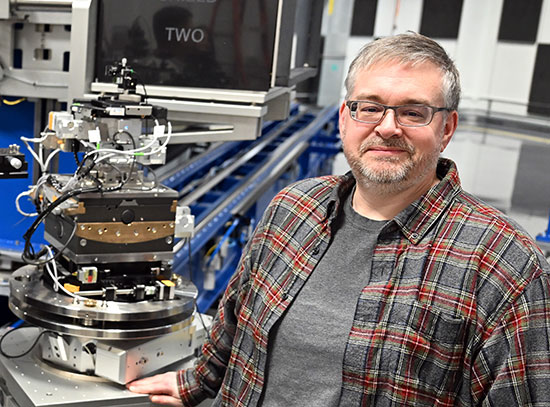

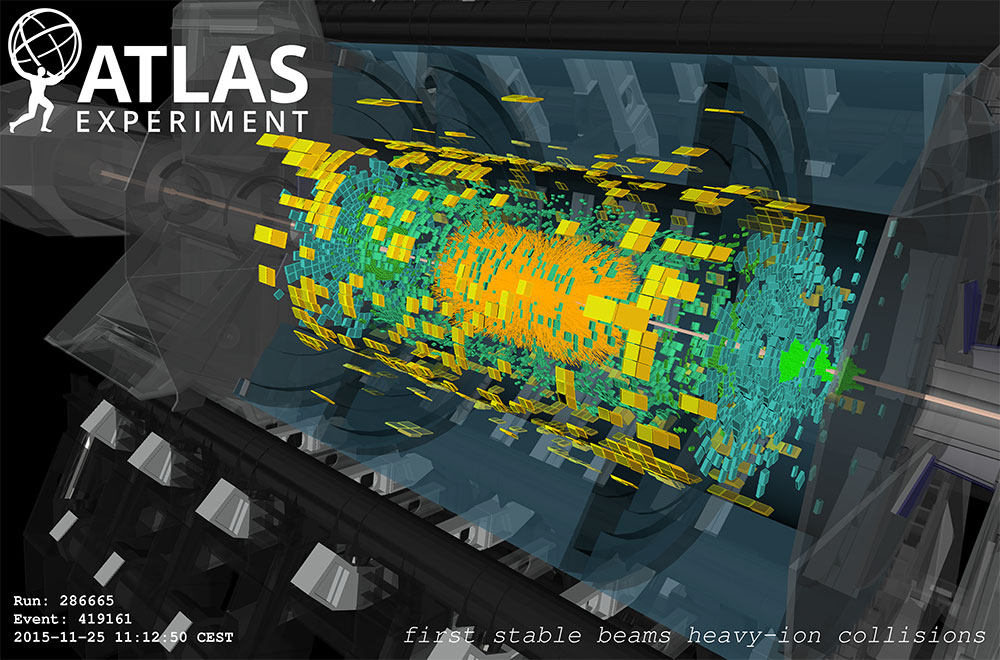

This is an example of a heavy-ion collision event recorded by ATLAS in November 2015. This analysis used data from the entire 2015 run. Tracks reconstructed from hits in the inner tracking detector are shown as orange arcs curving in the solenoidal magnetic field. The green and yellow bars indicate energy deposits in the Liquid Argon and Scintillating Tile calorimeters respectively. (ATLAS Collaboration)

UPTON, N.Y. — Scientists analyzing data from heavy ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — the world’s most powerful particle collider, located at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research — have new evidence that a pattern of “flow” observed in particles streaming from these collisions reflects those particles’ collective behavior. The measurements reveal how the distribution of particles is driven by pressure gradients generated by the extreme conditions in these collisions, which mimic what the universe was like just after the Big Bang.

The research is described in a paper published in Physical Review Letters by the ATLAS Collaboration at the LHC. Scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University played leading roles in the analysis.

The international team used data from the LHC’s ATLAS experiment to analyze how particles flow outward in radial directions when two beams of lead ions — lead atoms stripped of their electrons — collide after circulating around the 17-mile circumference of the LHC at close to the speed of light. The findings offer new insight into the nature of the hot, dense matter generated in these collisions —with temperatures more than 250,000 times hotter than the sun's core. These extreme conditions essentially melt the protons and neutrons that make up the colliding ions, setting free their innermost building blocks, quarks and gluons, to create a quark-gluon plasma (QGP).

enlarge

enlarge

Jiangyong Jia, a physicist at Brookhaven National Laboratory and Stony Brook University, left, led and oversaw this research on radial flow by his graduate student, Somadutta Bhatta, right, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at Utrecht University in the Netherlands and NIKHEF, the Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics. In this photo, the two are at the Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, Washington. (Courtesy of Somadutta Bhatta)

“Earlier measurements revealing that particles flow collectively from heavy ion collisions were central to the discovery of the quark-gluon plasma at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC),” said Jiangyong Jia, a physicist at Stony Brook University and Brookhaven Lab, where RHIC operates as a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research. Jia conducts research at both RHIC and the LHC and led the new ATLAS analysis. “The new results from ATLAS, while confirming the fluid-like nature of the QGP, also reveal something new because the type of flow we studied, ‘radial’ flow, has a different geometric origin from the ‘elliptic’ flow studied previously, and it is sensitive to a different type of viscosity in the fluid system.”

The ATLAS findings are supported by measurements at ALICE, another LHC experimental detector, which analyzed the same kind of collisions in a complementary way. ALICE has published its results in the same issue of Physical Review Letters.

A look back at elliptic flow

“In some ways, these radial flow measurements are completing a story that started the minute RHIC turned on,” said Peter Steinberg, another Brookhaven Lab physicist who has studied both RHIC and LHC collisions and is a co-author on the ATLAS paper.

The earliest data from RHIC, first released in 2001, revealed directional differences in particle flow patterns from Big Bang-simulating collisions of gold ions. Scientists saw an elliptical pattern, with more particles emerging along the reaction plane defined by the direction of the two colliding ions, than transversely perpendicular to it.

RHIC physicists postulated that this elliptic flow was driven by the football-like shape of the overlap region between spherical gold ions colliding off-center. Asymmetric pressure gradients in this oblong fireball would push more particles out along the waistband of the football than toward its pointed ends.

This collective behavior was at first surprising because it indicated that quarks and gluons continue to interact strongly even after being freed from their usual confined arrangements within protons and neutrons. The elliptic flow was so extreme that physicists declared it was coming from a nearly frictionless perfect liquid — one with extremely low shear viscosity.

enlarge

enlarge

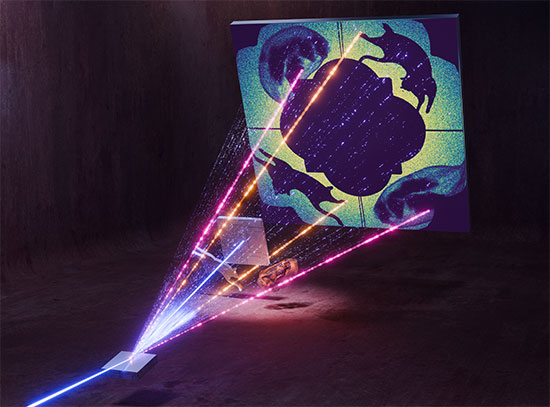

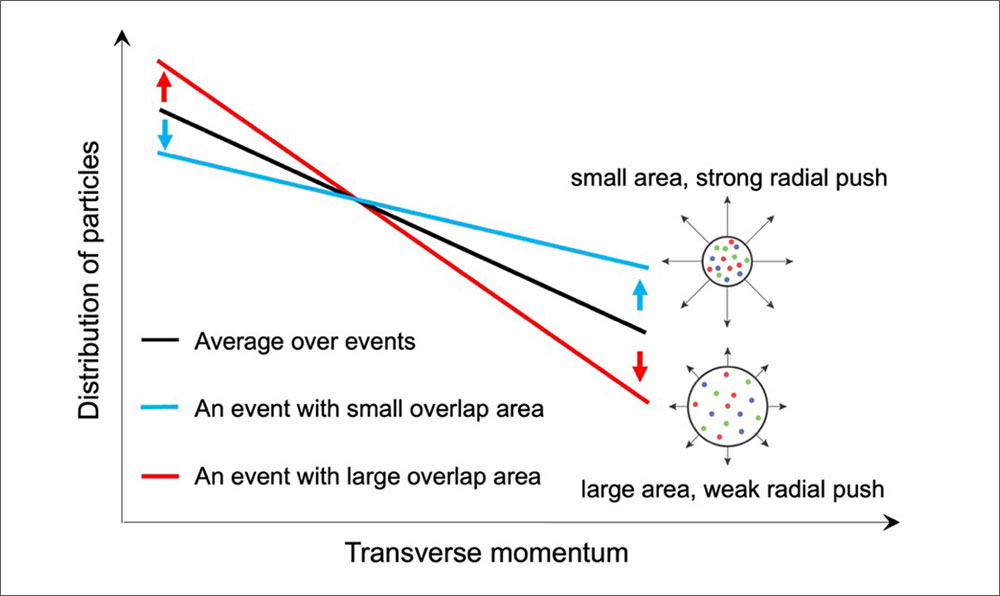

This schematic illustration shows how variations in radial flow affect particle transverse momentum distributions. Blue represents a smaller collision overlap area, which creates stronger pressure and pushes more particles to high momentum. Red represents a larger overlap area with weaker pressure, producing fewer high-momentum particles. All collisions shown produce the same total number of particles. (Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Exploring radial flow

“At first, elliptic flow was easier to study, and we had a much simpler expectation of how it should behave, so we mostly focused on that,” said Jia. But he noted that particles produced from the strongly interacting perfect fluid should also exhibit collective radial flow, driven by the symmetric component of the outward pressure gradient.

“People had studied radial flow at both RHIC and the LHC, but they didn't study how the correlations between faster and slower particles in each event vary with transverse momentum or with their angle relative to the beam direction,” Jia said.

In 2020, a theory paper published by Bjoern Schenke of Brookhaven Lab, Derek Teaney of Stony Brook University, and Chun Shen of Wayne State University, who was also a research fellow at the RIKEN BNL Research Center at that time, established a framework connecting momentum-dependent radial flow to the symmetric outward pressure, which is determined by the overall size of the QGP fireball rather than its shape. The new ATLAS paper describes the search for evidence to support this connection in data from the LHC’s lead ion collisions.

The theorists’ model predicted how the relative abundance of faster- and slower-moving particles produced transversely in each collision — that is, particles with higher and lower momentum — should change depending on the size of the collision overlap region. “For collisions producing the same overall number of particles, smaller, more tightly packed blobs of a quark-gluon plasma should have a stronger pressure gradient and a stronger radial expansion than larger, more dilute collisions,” Jia explained. That means more fast-moving particles and fewer slow ones should emerge from smaller collisions than from those with a larger, less pressure-cooked QGP.

“It’s like if you put the same amount of water into two different sized balloons and poked a hole in each; the water is going to come out faster from the smaller balloon because it’s under higher pressure,” said Somadutta Bhatta, who conducted this research as a Stony Brook University Ph.D. student under Jia’s mentorship and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Utrecht University in the Netherlands and NIKHEF, the Dutch National Institute for Subatomic Physics.

Bhatta searched the ATLAS data for signs of this relationship. He used two-particle correlations — the same technique used to study elliptic flow — to track the transverse momentum distribution of emitted particles event by event. He found the expected fluctuations in transverse momentum distribution driven by the size of the QGP fireball and demonstrated through a series of checks that the relationship between radial flow and QGP size holds at all angles along the beam direction.

“Our results confirm that radial flow, like elliptic flow, is truly a global collective phenomenon,” Bhatta said. “The outward radial push is carried by all the particles that are produced in each collision event.”

Using radial flow to study the QGP

As Steinberg noted, “The results show that, event by event, when you make a single speck of a QGP, you can see this correlation between the overall flow and the way the number of particles at high momentum goes up and the number of low momentum particles goes down. And no special shape of the QGP is required to drive this expansion.”

Radial flow measurements should help scientists understand microscopic properties of the QGP, particularly its bulk viscosity.

“Bulk viscosity can be described as resistance to outward expansion,” Bhatta said. That’s quite different from the shear viscosity that established the nearly friction-free “perfection” of the QGP fluid, which depends on differences in flow between different directions. In a radially expanding system, bulk viscosity can still slow the expansion down if the system is compressible.

“That means we can use our measurements of radial expansion to test how compressible the QGP is,” Jia said.

“Having a way to study flow and collective behavior without relying on its shape will also be particularly important in studying tiny drops of QGP created in collisions of nuclei much smaller than lead or gold ions,” Steinberg said. “In those small systems, we’re having trouble determining whether the shape is even measurable.”

Next steps might also include a deeper dive into the RHIC heavy-ion data.

“This has been an enormously successful collaboration between theorists and experimentalists at Brookhaven Lab and Stony Brook University,” said Michael Begel, the ATLAS group leader at Brookhaven. “It also showcases how a small group of people from Brookhaven have contributed to the CERN heavy ion program, creating synergies from the opportunities we’ve had with both RHIC and the LHC running at the same time.”

Jia noted that this project gave him a way to leverage knowledge gained at the LHC for his work in RHIC’s STAR collaboration, and vice versa from STAR to the LHC, which operates at significantly higher energies.

“I find this intersection across energies very useful to move the science forward,” he said. “These two facilities are really very complementary.”

Brookhaven Lab and Stony Brook University contributions to this ATLAS analysis — along with RHIC operations and U.S. participation in ATLAS more broadly — were funded by the DOE Office of Science. The scientific paper on the ATLAS research lists additional detailed funding, including from international partner institutions and agencies.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22793 | INT/EXT | Newsroom