Remembering Nobel Laureate Tsung-Dao (T.D.) Lee

August 8, 2024

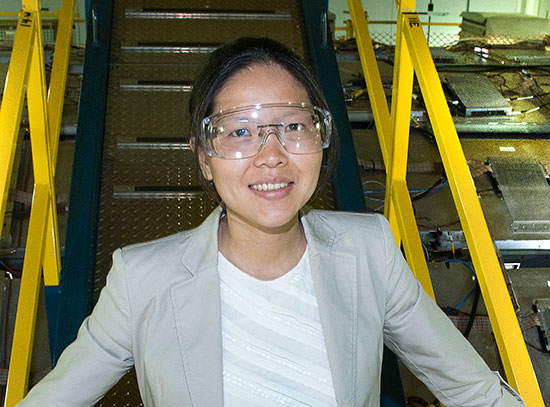

Tsung-Dao (T.D.) Lee at Brookhaven Lab in 2007 (Joe Rubino/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

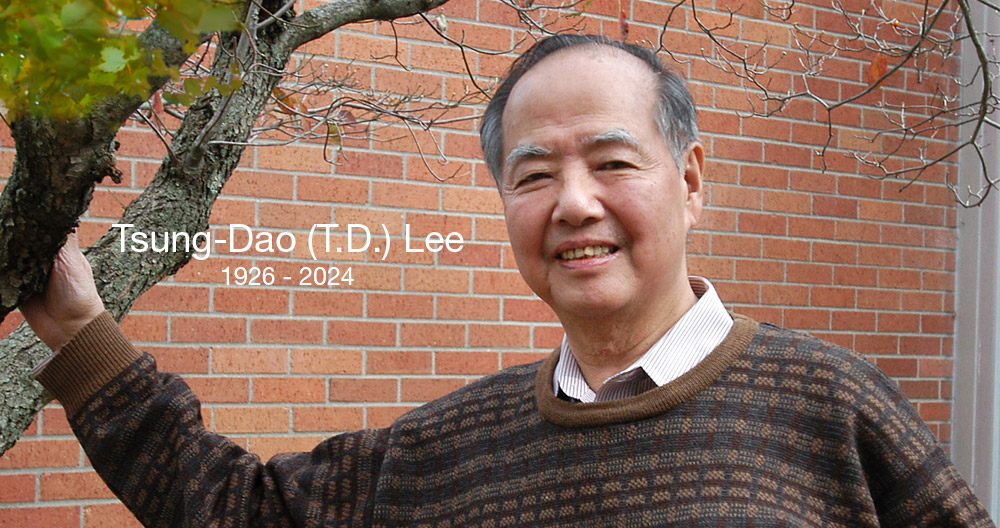

Physicist Tsung-Dao (T.D.) Lee, who shared the first Nobel Prize among seven awarded for discoveries made at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, died Aug. 4. He was 97.

Lee and Chen Ning (C.N.) Yang, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957 for a theoretical discovery that radically questioned one of physics' basic tenets. During his prodigious career, much of which he spent as a professor at Columbia University, Lee also served as first director of the RIKEN BNL Research Center (RBRC), from 1997 to 2003.

"T.D. Lee was a once-in-a-generation theoretical physicist, whose extraordinary work and mentorship of young scientists has had lasting impact," said Brookhaven Lab Director JoAnne Hewett, who is also a theoretical physicist. "Lee and Yang's theoretical formulation of parity violation — later proved experimentally by Chien-Shiung [C.S.] Wu — was groundbreaking and is the foundation of the weak interactions and today’s Standard Model of particle physics. I served on panels with T.D. and was always in awe of his presence."

"Scientists at Brookhaven created the puzzles of physics experimentally and then they solved them theoretically…When Lee and Yang joined colleagues at Brookhaven's beach outings at Westhampton on Fridays, they would draw equations in the sand with sticks."

— Robert Crease

Former Brookhaven Lab Director Nick Samios who, like Lee, also served as RBRC director, said, "T.D. Lee was a brilliant, pragmatic physicist. He was among many professors who spent their summers at Brookhaven. And he was a major force, helping organize centers and experiments, strengthening relationships for science collaborations among the U.S., China, Japan, and Europe.

"T.D. also was an intimate advisor," Samios continued. "When the ISABELLE project was cancelled in the 1980s and Brookhaven had to adapt, he encouraged a shift in emphasis from particle physics to nuclear physics, the importance of looking for quark-gluon plasma, and the building of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider."

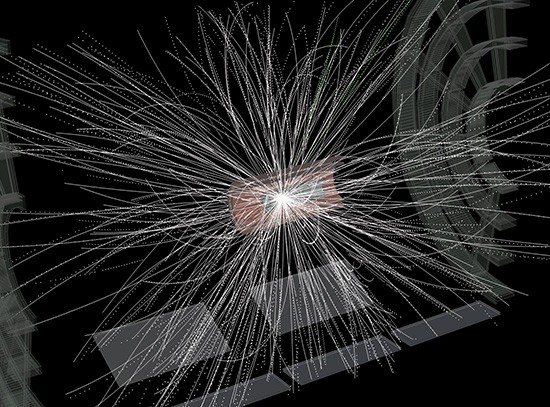

Lee's efforts, among many others', led to the completion of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in 2000. RHIC is a DOE Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at Brookhaven Lab. Quark-gluon plasma, a "perfect liquid" of freely flowing quarks and gluons, was discovered in 2005 as a result of experiments at RHIC.

Brookhaven's research in nuclear physics — the study of the atom's nucleus — will continue with the completion of the future Electron-Ion Collider (EIC).

Nobel Prize for discovering parity violation

Lee and Yang spent much time at Brookhaven Lab. In 1956, they interpreted results of particle decay experiments from the Cosmotron at Brookhaven. They found that the fundamental and supposedly absolute law of parity conservation had been violated.

enlarge

enlarge

T.D. Lee (L) and C.N. Yang. (Photo: Alan W. Richards, courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives)

Lee and Yang's studies concerned two particles — the tau and the theta, now called kaons — which had the same masses, lifetimes, and scattering behaviors. Because these particles decayed differently, however, the law of parity conservation required these similar particles be considered different from each other.

Lee and Yang formulated a theory suggesting that weak interactions of radioactive decay could violate the parity conservation law. Results from experiments proposed by Lee and Yang proved their theory correct.

They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957 for their discovery.

“To a large extent, during these years, scientists at Brookhaven created the puzzles of physics experimentally, and then they solved them theoretically," explained Robert Crease, a professor in the Department of Philosophy at Stony Brook University, who has written several books on the history of Brookhaven Lab.

"Lee and Yang used to shout at each other at the top of their lungs in their Physics office, trying to figure out why taus and thetas seemed the same but decayed differently," Crease said. "When Lee and Yang joined colleagues at Brookhaven's beach outings at Westhampton on Fridays, they would draw equations in the sand with sticks."

More memories of T.D. Lee

Hong Ma, chair of the Physics Department at Brookhaven Lab, said, "T.D. was revered as a great mentor for generations of physicists who followed his footsteps. He helped to bridge the gap between east and west and fostered collaboration and understanding across culture boundaries."

enlarge

enlarge

From left: Nobel Laureates T.D. Lee, Leon Lederman, Mel Schwartz, Jack Steinberger, and Samuel Ting at Brookhaven Lab in 1989. (Roger Stoutenburgh/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Peter Bond is a now-retired physicist and long-time Brookhaven employee whose titles included interim laboratory director. He also served as RBRC's deputy director when Lee led the center.

Bond said, "T.D. not only had a large impact in physics with his research, he also played a vital role in growing the community of talented young experimental and theoretical scientists around the world through his creative view of how the RIKEN-BNL Research Center should operate. RBRC would not have permanent positions and, instead, recruited and helped develop such wonderful talent hired from around the globe, including many in the U.S."

That "talent" included Abhay Deshpande who, today, works in a number of roles at Brookhaven, including interim associate lab director for Nuclear and Particle Physics as well as director of EIC science. He is also a SUNY Distinguished Professor at Stony Brook University.

"As an early RBRC Fellow, I fondly remember T.D. Lee and his genuine interest in talking to and encouraging us as we started on our research and academic careers." Deshpande said. "While mourning his passing, we should celebrate his enormous contributions to science, particularly at Brookhaven."

2024-22034 | INT/EXT | Newsroom