A Smashing Success: Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider Wraps up Final Collisions

Milestone caps a quarter century of groundbreaking discoveries — with more to come from final run's largest-ever dataset — plus technological advances in accelerators, detectors, and computing

February 6, 2026

enlarge

enlarge

Darío Gil, the U.S. Department of Energy's Under Secretary for Science, right, and Interim Laboratory Director John Hill officially ended the operational era of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at a capstone collision event held at Brookhaven National Laboratory on Friday, Feb. 6, 2026. (Kevin Coughlin/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

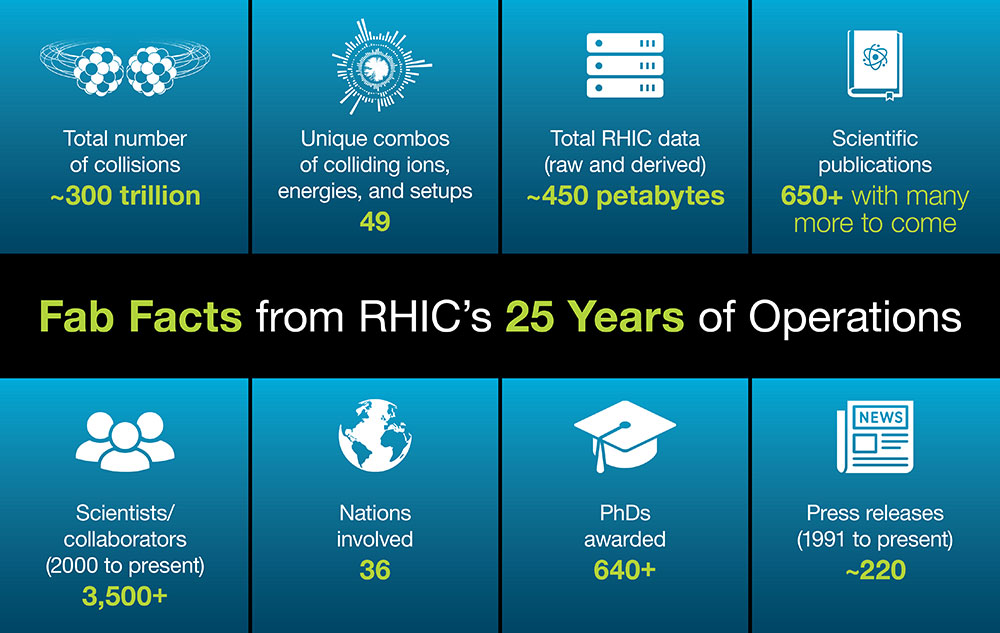

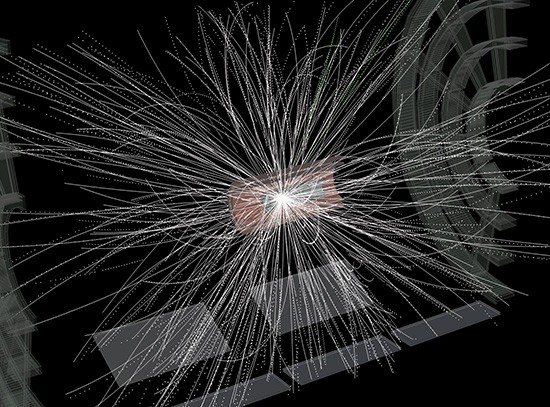

UPTON, N.Y. — Just after 9 a.m. on Friday, Feb. 6, 2026, final beams of oxygen ions — oxygen atoms stripped of their electrons — circulated through the twin 2.4-mile-circumference rings of the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and crashed into one another at nearly the speed of light inside the collider’s two house-sized particle detectors, STAR and sPHENIX. RHIC, a nuclear physics research facility at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, has been smashing atoms since the summer of 2000. The final collisions cap a quarter century of remarkable experiments using 10 different atomic species colliding over a wide range of energies in different configurations. The RHIC program has produced groundbreaking discoveries about the building blocks of matter and the nature of proton spin and technological advances in accelerators, detectors, and computing that have far surpassed scientists’ expectations when this discovery machine first turned on.

“RHIC has been one of the most successful user facilities operated by the DOE Office of Science, serving thousands of scientists from across the nation and around the globe,” said DOE Under Secretary for Science Darío Gil. “Supporting these one-of-a-kind research facilities pushes the limits of technology and expands our understanding of our world through transformational science — central pillars of DOE’s mission to ensure America’s security and prosperity.”

enlarge

enlarge

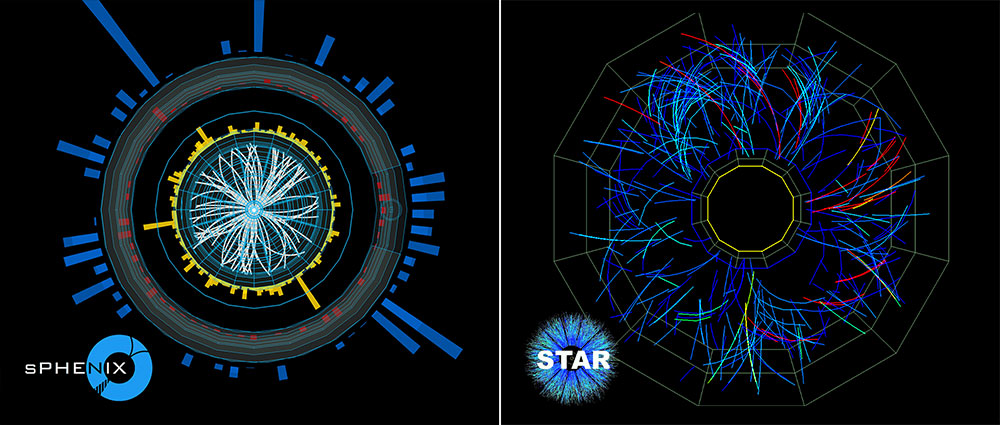

Some of the final collisions captured by the sPHENIX and STAR detectors at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, a nuclear physics research facility at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Collisions were between two beams of oxygen nuclei smashing into one another at nearly the speed of light. (sPHENIX and STAR Collaborations)

Gil was in the Main Control Room of Brookhaven Lab’s collider complex to officially end the 25th and final run at RHIC in advance of announcing the next major milestone in the construction of the Electron-Ion Collider (EIC), a state-of-the-art nuclear physics research facility that will be built by reusing major components of RHIC.

“It’s been an amazing run,” said Wolfram Fischer, chair of Brookhaven Lab’s Collider-Accelerator Department (C-AD), speaking of the entirety of the RHIC program. As head of C-AD, Fischer is responsible for the day-to-day, year-to-year operations of the collider and all its ancillary accelerator infrastructure. “Experiencing the challenges of first trying to get beams to circulate during commissioning in the fall of 1999, one could not have dreamed how far the performance of this machine would come,” he said. “We’ve pushed well beyond the original design in terms of the number of collisions we can produce, the energy range of those collisions, the variety of ions we’ve collided, and our ability to align the spins of protons and maintain a high degree of this alignment or polarization.”

The 25th and final run produced the largest-ever dataset from RHIC’s most energetic head-on smashups between two beams of gold ions, among the heaviest ions collided at RHIC. It also yielded a treasure trove of proton-proton collisions that will provide essential comparison data and insight into proton spin, a set of low-energy fixed target collisions to complete RHIC’s “beam energy scan,” and a final burst of oxygen-oxygen interactions. All this data will add to that collected previously by RHIC’s detectors — STAR, which has been running with many upgrades since RHIC’s beginning; PHENIX, another original RHIC detector that ceased operations in 2016; PHOBOS and BRAHMS, two smaller original detectors that ran from 2000 through 2005 and 2006, respectively; and sPHENIX, RHIC’s newest most rapid-fire collision “camera,” which came online in 2023.

This final run generated the primary data set for the new sPHENIX experiment. This year, sPHENIX accumulated more than 200 petabytes of raw data — or 200 quadrillion bytes — more than all previous RHIC raw datasets combined. This massive dataset includes 40 billion snapshots of the unique form of matter generated in gold-ion collisions.

enlarge

enlarge

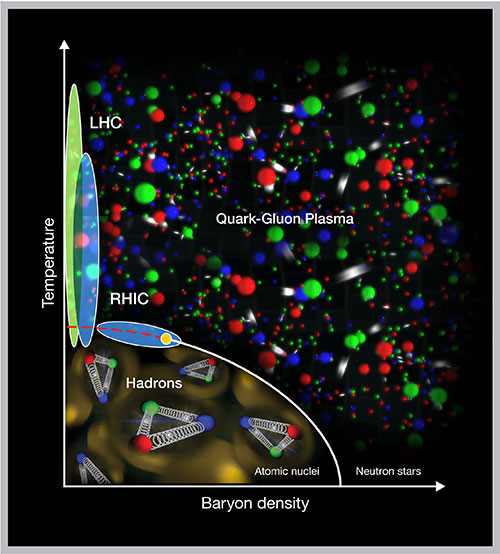

Collisions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider recreate matter as it existed just after the Big Bang nearly 14 billion years ago. The collisions "melt" the protons and neutrons of atomic nuclei to "set free" those particles' innermost building blocks — quarks and gluons — to create a quark-gluon plasma that mimics the conditions of the early universe. (Tiffany Bowman/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Collectively, the RHIC measurements will fill in missing details in physicists’ understanding of how a soup of fundamental particles known as quarks and gluons — which last existed in nature some 14 billion years ago, a microsecond after the Big Bang — coalesced and converged to form the more ordinary atomic particles that make up everything visible in our world today. Recreating this primordial matter, known as a quark-gluon plasma (QGP), was the primary reason for building RHIC. RHIC’s energetic collisions of heavy ions such as gold were designed to set quarks and gluons free from “confinement” within protons and neutrons by melting the boundaries of these nuclear particles.

Thanks to considerable contributions from Japan’s RIKEN institute, RHIC was also built with unique capabilities for polarizing protons so that physicists could explore the origins of proton spin. This intrinsic quantum property, somewhat analogous to a planet spinning on its axis, has been leveraged to develop powerful technologies like nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and medical MRIs. RHIC’s polarized proton collisions have opened a new window into the mystery of how spin arises from the proton’s quarks and gluons.

PHENIX and STAR have both collected and published results from large swaths of spin-polarized collisions using selection “triggers” to decide which events to capture and study. During Run 25, sPHENIX became the world’s first detector to record a continuous streaming dataset from RHIC’s spin-polarized proton collisions — thus eliminating the need for triggers and potentially paving the way for unanticipated discoveries.

“This final RHIC run, with its impressive dataset, is a capstone that exemplifies the success of the entire RHIC program,” said John Hill, interim director of Brookhaven Lab. “The scientists, engineers, and technicians at Brookhaven deserve huge credit for their dedication and innovation throughout the operating life of RHIC — and for continually finding new ways to maximize the scientific output of this remarkable machine. We are also extremely grateful for the continued support of the U.S. Department of Energy, and for our collaborators from other DOE labs, U.S. universities, and scientific institutions around the globe. This exploration of the matter that makes up our world and of how it came to be has been, and will continue to be, a truly international endeavor.”

Captivating discoveries

enlarge

enlarge

This image maps out the phases of nuclear matter under various conditions of temperate and baryon density. Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) collisions have helped scientists map out many points in this nuclear landscape, including how matter made of hadrons, including protons and atomic nuclei, transforms into a quark-gluon plasma under the extreme conditions created in collisions at RHIC. (Brookhaven National Laboratory)

In early 2001, as the earliest RHIC data came out, some scientists were convinced that they’d seen signs of the post-Big-Bang QGP. But the data also presented puzzling surprises. Instead of the predicted uniformly expanding gas of quarks and gluons, the matter created in RHIC’s collisions seemed to flow more like a liquid — and, remarkably, one with extremely low viscosity. Additional experiments and a careful multiyear analysis led the four original RHIC collaborations to conclude in 2005 that RHIC was generating a nearly “perfect” liquid. By 2010, they had sufficient evidence to declare this liquid hot enough to be the long-sought QGP.

Since then, RHIC physicists have been making precision measurements of the QGP, including its temperature at different stages, how it swirls — it’s the swirliest matter ever! — how quarks and gluons in the primordial soup transition under various conditions of temperature and pressure to the nuclear matter that makes up atoms in our world, and how collisions of even small particles can create tiny drops of the QGP. They’ve explored exotic forms of nuclear matter such as that found in neutron stars, detected traces of the heaviest exotic antimatter ever created in a laboratory, and explored how visible matter emerges from the “nothingness” of empty space. The sPHENIX experiment has only recently published its first physics results, laying the foundation for its future of scientific insights.

“RHIC transformed nuclear physics by demonstrating the remarkable consequences of ‘boiling the vacuum,’ to paraphrase renowned physicist T. D. Lee’s description of matter governed by quantum chromodynamics (QCD),” said Brookhaven Lab theorist Raju Venugopalan. “In QCD — the theory that describes quarks and gluons and their interactions — findings from RHIC propelled the rapid development of new analytical approaches and high-performance computing. The RHIC data also sparked several unanticipated connections between the behavior of the QGP fluid and strongly correlated condensed matter systems, including ultra-cold atoms, as well as links to concepts such as quantum entanglement and the formation and evaporation of black holes.”

Advances in nuclear physics theory and the enormous RHIC datasets have also pushed the evolution of supercomputers, AI methods for analyzing “big data,” and the infrastructure needed to store and share data seamlessly with RHIC collaborators around the world. In 2024, Brookhaven’s data center — which also houses data from the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, and other experiments — passed the milestone of storing 300 petabytes of data, the largest compilation of nuclear and particle physics data in the U.S. With the newest data from RHIC and ATLAS, the total now tops 610 petabytes.

In the proton spin program, RHIC's measurements greatly improved the precision with which scientists could determine gluons’ contribution to proton spin, along with the contribution from quarks. This effort was motivated by surprising results from experiments elsewhere in the 1980s showing that quarks contribute only a fraction to this quantum property. Gluons were initially assumed to contribute the rest. RHIC’s measurements reveal that gluons contribute about as much as the quarks — not enough to fully solve the “spin puzzle.” A more recent analysis established that at least some of the gluons are spin aligned with the spin of the proton they are in. But there is still more to explore in this spin puzzle.

“Spin is one of the fundamental quantum numbers of every elementary particle in the universe except one, the Higgs,” said Elke Aschenauer, a Brookhaven Lab physicist who has played a pivotal role in RHIC’s spin physics program. “RHIC’s measurements have established the groundwork for understanding the complexity of proton spin. The future EIC will be a precision machine for studying proton spin.”

All Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider data is stored on tape at Brookhaven Lab's data center. When physicists want access to a particular dataset — or multiple sets simultaneously — a robot grabs the appropriate tape(s) and mounts the desired data to disk within seconds. Collaborators around the world can tap into the data as if it were on their own desktop. (David Rahner/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Continuing legacy

enlarge

enlarge

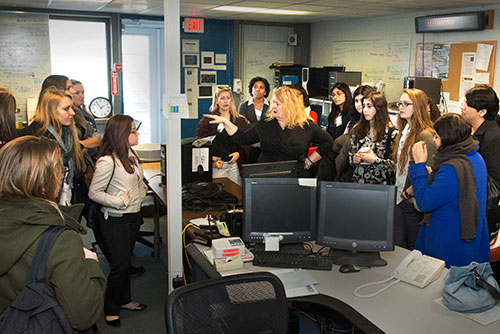

Brookhaven Lab physicist Elke Aschenauer in the STAR control room with a group of students. Students engaged in research at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider often go on to apply their skills in a wide range of areas beyond physics, including nuclear medicine, national security, energy generation, space exploration, finance, and more. (Roger Stoutenburgh/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

Even with so many impressive discoveries in the books, RHIC physicists say there will be many more to come for at least another decade.

“The science mission of RHIC will continue until we analyze all the data and publish all the papers,” said Abhay Deshpande, Brookhaven Lab’s associate laboratory director for nuclear and particle physics. He emphasized how important it will be to preserve RHIC’s data for future scientific analyses.

RHIC’s data will also continue to serve as an essential bridge between ongoing and planned experiments exploring nuclear matter at lower collision energies — for example at the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) being built in Germany and the Super Proton Synchrotron at CERN — and at much higher energies at CERN’s LHC.

“Analyzing the latest RHIC data will also help train the next generation of physicists needed to run and analyze data from future experiments,” said Lijuan Ruan, a Brookhaven Lab physicist and co-spokesperson for the STAR Collaboration.

A big part of that future will take place right here at Brookhaven National Laboratory where major components of the RHIC accelerator complex will live on in a new nuclear physics research facility, the world’s only polarized Electron-Ion Collider. Engineers and technicians will remove one of RHIC’s ion storage rings and replace it with a new ring for storing accelerated electrons inside the existing accelerator tunnel. Meanwhile, the other RHIC ring, refurbished for its new mission, will receive ions accelerated by C-AD’s existing injector complex, traveling around the tunnel in the opposite direction from the electrons. Scientists will leverage the experience gained during 25 years of RHIC operations — as well as reams of RHIC accelerator physics data — to develop and train new AI algorithms designed to optimize EIC accelerator performance.

enlarge

enlarge

The Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) will make use of existing components of Brookhaven's Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), including its ion sources, pre-accelerator chain, and a superconducting magnet ion storage ring. A new electron storage ring will be built inside the existing collider tunnel so that collisions can take place at points where the stored ion and electron beams cross. (Valerie A. Lentz/Brookhaven National Laboratory)

When electrons collide with ions where the two EIC rings cross, the action will be captured by a brand-new particle detector. Instead of recreating the early universe, these microscope-like interactions will enable precision measurements that reveal how quarks and gluons are organized and interact within matter as we know it in today’s world.

“We’ll learn how quarks and gluons generate mass, how their interactions contribute to proton spin, and much more that will revolutionize our understanding of matter — much as the science we've explored at RHIC has,” said Deshpande, who also serves as director of science for the EIC. “This is the future of Brookhaven Lab and nuclear physics in the U.S.”

Daniel Marx, one of the accelerator physicists working on the design of the EIC’s new electron storage ring, said, “It’s going to be very challenging, but also exciting. We’ll be doing things that have never been done before.”

Perhaps Marx was echoing the sentiments of the physicists who originally built RHIC, demonstrating another big part of RHIC’s legacy: an ongoing willingness to tackle unprecedented scientific and technological challenges.

“We are confident that we have the people who will make the EIC happen because of the expertise we have developed by building and running RHIC,” Deshpande said.

RHIC and the future EIC are funded primarily by the DOE Office of Science.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on social media. Find us on Instagram, LinkedIn, X, and Facebook.

2026-22794 | INT/EXT | Newsroom